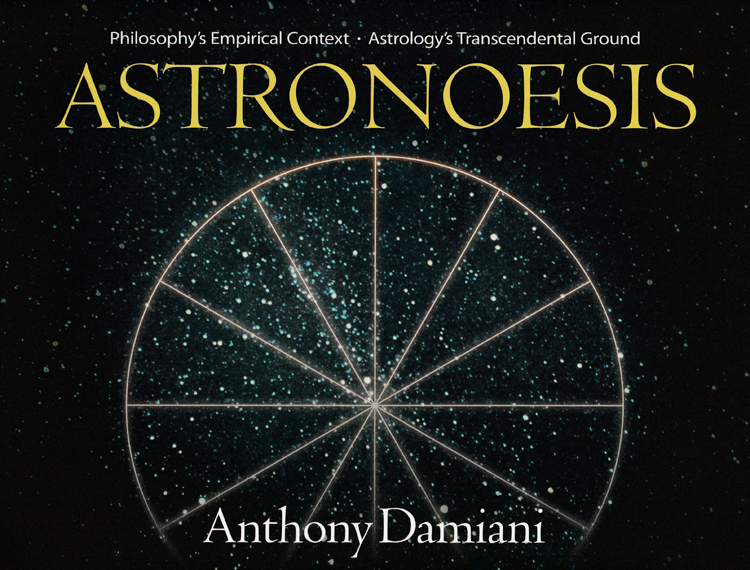

Song and Its Fountains

By A.E.

Retail/cover price: $10.95

Our price : $8.76

Save 40% today (online only) : $6.57

(You save $4.38!)

About this book:

Song and Its Fountains

by A.E.

"Offers vistas so endless there is no possibility of getting to their end.” —The New York Times

For A.E., art and literature were useful only so far as they express or inspire some form of spiritual realization

Subjects: Biography, Spirituality

5.5 x 8.5, paperback, 110 pages

ISBN 10: 0-943914-52-3

ISBN 13: 978-0-943914-52-7

Book Details

“For those who would see with a poet's clarity of vision into the depth of a poet's mind, for those for whom the word 'soul' has still a place in the vocabulary, this book offers vistas so endless there is no possibility of getting to their end.” —The New York Times, original review, April, 1932

Song and Its Fountains is an inspired “retrospective meditation” on the process of inspiration. It is immensely valuable to anyone seeking to understand or stimulate the element of infinity in the human heart.

This back-in-print 1932 classic sparkles throughout with the intuitive vision, philosophic wisdom, and robust practicality that made this much loved, versatile genius the pivotal figure of the Celtic literary renaissance and the emergence of modern Ireland. Song is an invigorating journey into the heart of inspiration with a guide who loved Plotinus and lit Stephen MacKenna’s fire. Paul Brunton recommended A.E. highly. This may be his finest work.

Song and Its Fountains is an inspired “retrospective meditation” on the process of inspiration. It is immensely valuable to anyone seeking to understand or stimulate creativity or visionary power.

Though widely recognized as a pivotal figure in the Celtic literary renaissance and the emergence of modern Ireland, AE held no stock in art and literature — or anything else, for that matter — as ends in themselves. For him, they became noble and useful only insofar as they expressed or inspired some form of spiritual realization. “Art for art’s sake,” he wrote in a letter, “is considering the door as a decoration and not for its uses in the house of life.” Monk Gibbon observed (in his foreword to Letters from AE), that “the key to AE’s life is the fact that he had elected to be a student of esoteric wisdom, and that his interest in literature, in poetry, in painting and in practical affairs were all to a large extent rooted in this original impulse.”

AE’s dictum was “Seek on earth what you have found in heaven.” Much of his central philosophy is expressed in a section of a letter he wrote to the Irish Times in which he says: “Ideals descend on us from a timeless world, but they must be related to time; for this world has its own good, and, if we do not render it its lawful rights, neither will it receive our message, and Heaven and Earth are divorced and both are wronged.”

“AE” is a pseudonym for George William Russell, who was born in Lurgan, County Armagh, Ulster, on April 10, 1867, and formally educated at the Rathmines School in Dublin. He died in London on July 17, 1935, three years after the original publication of Song and Its Fountains.

Throughout his life, AE exuded an idiosyncratic charm, an astonishing blend of intuitive wisdom and robust earthy practicality that earned the admiration and devoted friendship of many of his contemporaries. At the turn of the century, he formed lifelong friendships, for example, with W.B. Yeats, George Moore, Lord Dunsany, and James Stephens. Among the many writers who first flourished under his editorial guidance were Frank O’Connor, Sean O’Faolain, Liam O’Flaherty, F.R. Higgins, L.A.G. Strong, and Patrick Kavanagh.

AE was not only a poet, painter, essayist, journalist, and editor, he was also an astute economist with a comprehensive understanding of agricultural problems. During Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first administration, Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace invited AE to lecture in the United States on rural reorganization. Both the London Times and the Irish Times frequently gave him carte blanche for editorial comment on key political issues of his day.

AE’s uncommon practicality was rooted in establishing conscious communion with an inner order of genius that utters through the individual wiser things than the individual consciously knows. His extensive studies of the sacred literatures of Christianity, Brahmanism, Buddhism, Taoism, Hermeticism, Platonism, and Neoplatonism (most notably Plotinus) were all means to develop and strengthen this communion. He was constantly invigorated by writers like Emerson and Whitman who “have more permanent value . . . for they had something of the element of infinity in their being without which writers lose their hold over the imagination and which makes them belong to one wave in time however subtle or prodigal in humor they may be.”

His influence on the development of an integral East-West spirituality is immensely larger than has yet been credited appropriately. Late in his life, for example, he advised the young Paul Brunton: “Why go off to the East for light? If you believe in a World-Soul, then it should be possible to sit down even in a town like Dublin and look within until you contact that World-Soul and so gain all the spiritual light you seek. But perhaps your destiny compels you to go, for I foresee that you have an exceptional work to perform in threshing the corn of Eastern wisdom for the sake of Western students.” In his own monumental Notebooks, Paul Brunton often speaks with reverential fondness of AE as a “true Olympian . . . my beloved friend . . . that versatile Irishman [who] was a gifted painter as well as poet, economist as well as prose essayist, clairvoyant, seer, and, when I met him, more of a sage.”

For AE, nothing could be more practical than finding new ways to embrace and express the “element of infinity” in the human heart. Song and Its Fountains is his best testimony to the success he had in doing so, and to the methods that worked for him.

This re-issuing of the original 1932 edition has been lightly edited. Spelling and punctuation have been modernized in its prose sections, and exceptionally long paragraphs have been broken into shorter ones to make text pages more visually accessible. Original spelling, punctuation, and versing, however, have been retained in all the poetry.

“Why go off to the East for light? If you believe in a World-Soul, then it should be possible to sit down even in a town like Dublin and look within until you contact that World-Soul and so gain all the spiritual light you seek. But perhaps your destiny compels you to go, for I foresee that you have an exceptional work to perform in threshing the corn of Eastern wisdom for the sake of Western students.” This was the advice tendered me by my beloved friend, the distinguished Irish poet “A.E.,” a few weeks before he died. It was sound advice, as I found to my cost. Yet the force which drove me to disobey it was overwhelming. It was, as “A.E.” rightly surmised, my personal destiny. —Notebooks volume 8, chapter 6, #242

Seventy years ago that versatile Irishman who used the pen name A.E. published his collected poems. He was a gifted painter as well as poet, economist as well as a prose essayist, clairvoyant, seer, and, when I met him, more of a sage. . . . —Notebooks volume 9, chapter 4, #115

My lamented friend, the Irish poet A.E., wrote with his celestial pen, “We are in our distant hope,/ One with all the great and wise,/ Comrade, do not turn and grope/ For a lesser light that dies.” —Notebooks volume 11, chapter 13, #25

I remember one day when A.E. (George Russell), the Irish poet and statesman, chanted to me in his attractive Hibernian brogue some paragraphs from his beloved Plotinus that tell of the gods, although the number of words which stick to memory are but few and disjointed, so drugged were my senses by his magical voice. “All the gods are venerable and beautiful, and their beauty is immense. . . . For they are not at one time wise, and at another destitute of wisdom; but they are always wise, in an impassive, stable, and pure mind. They likewise know all things which are divine. . . . For the life which is there is unattended with labour, and truth is their generator and nutriment. . . . And the splendour there is infinite. . . .” —Notebooks volume 14, chapter 2, #120

Out of his own large experience of meditation, “Fear not the stillness,” wrote A.E. in a poem. —Notebooks volume 15, chapter 8, #56

These are the true Olympians, not the mythic beings of human creation. They may dwell apart on their mountain — like Sengai, the Japanese — or in the city with its crowds — like A.E., the Irishman. —Notebooks volume 16, chapter 3, 120

Bio coming soon.

Book Details

“For those who would see with a poet's clarity of vision into the depth of a poet's mind, for those for whom the word 'soul' has still a place in the vocabulary, this book offers vistas so endless there is no possibility of getting to their end.” —The New York Times, original review, April, 1932

Song and Its Fountains is an inspired “retrospective meditation” on the process of inspiration. It is immensely valuable to anyone seeking to understand or stimulate the element of infinity in the human heart.

This back-in-print 1932 classic sparkles throughout with the intuitive vision, philosophic wisdom, and robust practicality that made this much loved, versatile genius the pivotal figure of the Celtic literary renaissance and the emergence of modern Ireland. Song is an invigorating journey into the heart of inspiration with a guide who loved Plotinus and lit Stephen MacKenna’s fire. Paul Brunton recommended A.E. highly. This may be his finest work.

Song and Its Fountains is an inspired “retrospective meditation” on the process of inspiration. It is immensely valuable to anyone seeking to understand or stimulate creativity or visionary power.

Though widely recognized as a pivotal figure in the Celtic literary renaissance and the emergence of modern Ireland, AE held no stock in art and literature — or anything else, for that matter — as ends in themselves. For him, they became noble and useful only insofar as they expressed or inspired some form of spiritual realization. “Art for art’s sake,” he wrote in a letter, “is considering the door as a decoration and not for its uses in the house of life.” Monk Gibbon observed (in his foreword to Letters from AE), that “the key to AE’s life is the fact that he had elected to be a student of esoteric wisdom, and that his interest in literature, in poetry, in painting and in practical affairs were all to a large extent rooted in this original impulse.”

AE’s dictum was “Seek on earth what you have found in heaven.” Much of his central philosophy is expressed in a section of a letter he wrote to the Irish Times in which he says: “Ideals descend on us from a timeless world, but they must be related to time; for this world has its own good, and, if we do not render it its lawful rights, neither will it receive our message, and Heaven and Earth are divorced and both are wronged.”

“AE” is a pseudonym for George William Russell, who was born in Lurgan, County Armagh, Ulster, on April 10, 1867, and formally educated at the Rathmines School in Dublin. He died in London on July 17, 1935, three years after the original publication of Song and Its Fountains.

Throughout his life, AE exuded an idiosyncratic charm, an astonishing blend of intuitive wisdom and robust earthy practicality that earned the admiration and devoted friendship of many of his contemporaries. At the turn of the century, he formed lifelong friendships, for example, with W.B. Yeats, George Moore, Lord Dunsany, and James Stephens. Among the many writers who first flourished under his editorial guidance were Frank O’Connor, Sean O’Faolain, Liam O’Flaherty, F.R. Higgins, L.A.G. Strong, and Patrick Kavanagh.

AE was not only a poet, painter, essayist, journalist, and editor, he was also an astute economist with a comprehensive understanding of agricultural problems. During Franklin D. Roosevelt’s first administration, Secretary of Agriculture Henry Wallace invited AE to lecture in the United States on rural reorganization. Both the London Times and the Irish Times frequently gave him carte blanche for editorial comment on key political issues of his day.

AE’s uncommon practicality was rooted in establishing conscious communion with an inner order of genius that utters through the individual wiser things than the individual consciously knows. His extensive studies of the sacred literatures of Christianity, Brahmanism, Buddhism, Taoism, Hermeticism, Platonism, and Neoplatonism (most notably Plotinus) were all means to develop and strengthen this communion. He was constantly invigorated by writers like Emerson and Whitman who “have more permanent value . . . for they had something of the element of infinity in their being without which writers lose their hold over the imagination and which makes them belong to one wave in time however subtle or prodigal in humor they may be.”

His influence on the development of an integral East-West spirituality is immensely larger than has yet been credited appropriately. Late in his life, for example, he advised the young Paul Brunton: “Why go off to the East for light? If you believe in a World-Soul, then it should be possible to sit down even in a town like Dublin and look within until you contact that World-Soul and so gain all the spiritual light you seek. But perhaps your destiny compels you to go, for I foresee that you have an exceptional work to perform in threshing the corn of Eastern wisdom for the sake of Western students.” In his own monumental Notebooks, Paul Brunton often speaks with reverential fondness of AE as a “true Olympian . . . my beloved friend . . . that versatile Irishman [who] was a gifted painter as well as poet, economist as well as prose essayist, clairvoyant, seer, and, when I met him, more of a sage.”

For AE, nothing could be more practical than finding new ways to embrace and express the “element of infinity” in the human heart. Song and Its Fountains is his best testimony to the success he had in doing so, and to the methods that worked for him.

This re-issuing of the original 1932 edition has been lightly edited. Spelling and punctuation have been modernized in its prose sections, and exceptionally long paragraphs have been broken into shorter ones to make text pages more visually accessible. Original spelling, punctuation, and versing, however, have been retained in all the poetry.

“Why go off to the East for light? If you believe in a World-Soul, then it should be possible to sit down even in a town like Dublin and look within until you contact that World-Soul and so gain all the spiritual light you seek. But perhaps your destiny compels you to go, for I foresee that you have an exceptional work to perform in threshing the corn of Eastern wisdom for the sake of Western students.” This was the advice tendered me by my beloved friend, the distinguished Irish poet “A.E.,” a few weeks before he died. It was sound advice, as I found to my cost. Yet the force which drove me to disobey it was overwhelming. It was, as “A.E.” rightly surmised, my personal destiny. —Notebooks volume 8, chapter 6, #242

Seventy years ago that versatile Irishman who used the pen name A.E. published his collected poems. He was a gifted painter as well as poet, economist as well as a prose essayist, clairvoyant, seer, and, when I met him, more of a sage. . . . —Notebooks volume 9, chapter 4, #115

My lamented friend, the Irish poet A.E., wrote with his celestial pen, “We are in our distant hope,/ One with all the great and wise,/ Comrade, do not turn and grope/ For a lesser light that dies.” —Notebooks volume 11, chapter 13, #25

I remember one day when A.E. (George Russell), the Irish poet and statesman, chanted to me in his attractive Hibernian brogue some paragraphs from his beloved Plotinus that tell of the gods, although the number of words which stick to memory are but few and disjointed, so drugged were my senses by his magical voice. “All the gods are venerable and beautiful, and their beauty is immense. . . . For they are not at one time wise, and at another destitute of wisdom; but they are always wise, in an impassive, stable, and pure mind. They likewise know all things which are divine. . . . For the life which is there is unattended with labour, and truth is their generator and nutriment. . . . And the splendour there is infinite. . . .” —Notebooks volume 14, chapter 2, #120

Out of his own large experience of meditation, “Fear not the stillness,” wrote A.E. in a poem. —Notebooks volume 15, chapter 8, #56

These are the true Olympians, not the mythic beings of human creation. They may dwell apart on their mountain — like Sengai, the Japanese — or in the city with its crowds — like A.E., the Irishman. —Notebooks volume 16, chapter 3, 120

About A.E.

Bio coming soon.

.jpg)

.jpg)