Living Wisdom

Revisioning the Philosophic Quest By Anthony Damiani

Retail/cover price: $15.95

Our price : $11.16

(You save $4.79!)

About this book:

Living Wisdom

Revisioning the Philosophic Quest

by Anthony Damiani

"Anthony Damiani's work combines and balances the best of the spiritual and the material." —H.H. Dalai Lama

"A truly tremendous book . . ." —Parabola

Subjects: Philosophy, Spirituality

30% discount!

5.5 x 8.5, paperback

240 pages

ISBN 10: 0-943914-69-8

ISBN 13: 978-0-943914-69-5

Book Details

This book delivers, concisely and accessibly, the essence of the Paul Brunton / Anthony Damiani school of spiritual awakening and practice. It offers what many consider a satisfying vision of mature spirituality: a perspective that honors reason and beauty, cultivates intuition and mystical experience, fosters reverence and true prayer, and inspires practical action and morality. Its approach to self and world is as broad and deep as life itself, articulating the unique values of each of life’s many aspects.

As Robert Sardello wrote in his Parabola review: "People are starving to find meaning. But the one path that is open to the modern person, the spiritual path of thinking, is neglected . . . because there are not many individuals around who are dedicated to this path, because thinking has been captured by the forces of hardness. Perhaps this marvelous, this exciting, this truly tremendous book will give a new context for cognition—full of soul which reaches out to touch spirit. Wisdom can be approached only through the path of thinking-feeling, and we must be deeply grateful to Anthony Damiani for showing us the way again."

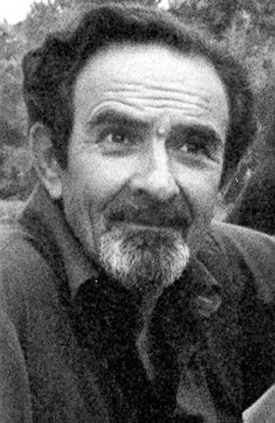

Anthony Damiani (1922–1984) founded the Wisdom’s Goldenrod Center for Philosophic Studies in 1972. Living Wisdom is an edited transcript of his commentaries and elaborations on the “What Is Philosophy?” section of Paul Brunton’s Notebooks.

See other tabs on this page for selections from the text and information about Anthony Damiani.

Also by Anthony Damiani from Larson Publications:

Looking into Mind

Standing in Your Own Way

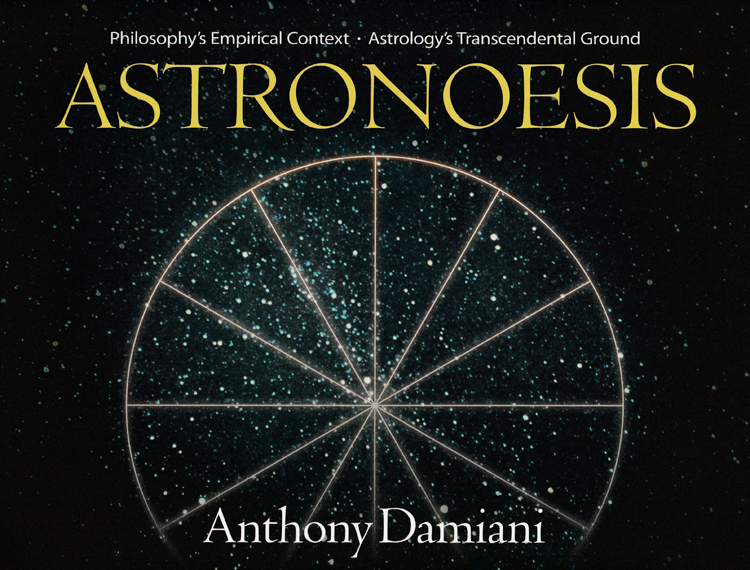

Astronoesis

"Those of us who love philosophy, cultivate it, and understand something about it, after a while will feel as though we are dissolving in that wonder, in that awe. It’s inevitable. You don’t even have to bring in self-abnegation, because it will happen very naturally if you truly cultivate philosophy." —Anthony Damiani

"Anthony Damiani is a philosophic genius . . . a fully qualified philosophic teacher." —Paul Brunton

"Anthony Damiani . . . a passionate and inspired philosopher." —Georg Feuerstein

"Anthony Damiani [was] a truly great man . . . one of my closest spiritual brothers . . . His work combines and balances the best of the spiritual and the material." —H.H. Dalai Lama

"People are starving to find meaning. But the one path that is open to the modern person, the spiritual path of thinking, is neglected . . . because there are not many individuals around who are dedicated to this path, because thinking has been captured by the forces of hardness. Perhaps this marvelous, this exciting, this truly tremendous book will give a new context for cognition--full of soul which reaches out to touch spirit. Wisdom can be approached only through the path of thinking-feeling, and we must be deeply grateful to Anthony Damiani for showing us the way again." —Robert Sardello, in Parabola

"Damiani was a visionary genius intent on peering into the heart of reality, making personal acquaintance with 'the wisdom-knowledge that sustains the cosmos.'"—The Mountain Astrologer

Contents

Editors’ Foreword

1. Introduction to the Philosophic Life

2. Philosophic Development

Stages of Development

The World-Mind Teaches You

Development and Balance of Knowing, Willing, and Feeling Leads to Insight

3. Enlightenment

Insight, Intuition, and Psyche

Insight and Manifestation

The Double Knower

Philosophic vs. Mystical Realization

Permanent Enlightenment vs. Temporary States

4. What a Philosopher Is

Appendix: Insight and Understanding

Introduction to the Philosophic Life

IT MAY BE ASKED why I insist on using the word "philosophy" as a self-sufficient name without prefixing it by some descriptive term or person’s name when it has held different meanings in different centuries, or been associated with different points of view ranging from the most materialistic to the most spiritualist. The question is well asked, although the answer may not be quite satisfactory. I do so because I want to restore this word to its ancient dignity. I want it used for the highest kind of insight into the Truth of things, which means into the Truth of the unique Reality. I want the philosopher to be equated with the sage, the man [sic] who not only knows this Truth, has this insight, and experiences this Reality in meditation, but also, although in a modified form, in action amid the world’s turmoil. (v13, 20:1.127 and Perspectives, p. 250)

ANTHONY: PB is not going to call you a philosopher if you haven’t experienced the higher states of consciousness. A theoretician or metaphysician who hasn’t experienced these states is not a philosopher. That’s the one distinction he’s making here.

IT IS PERHAPS the amplitude and symmetry of the philosophic approach which make it so completely satisfying. For this is the only approach which honours reason and appreciates beauty, cultivates intuition and respects mystical experience, fosters reverence and teaches true prayer, enjoins action and promotes morality. It is the spiritual life fully grown. (v13, 20:1.22 and Perspectives, p. 261)

ANTHONY: Philosophy is broad-based, as big as life itself. It finds proper due for all the different aspects in life. It finds their proper evaluation or their proper place.

There’s not only precision and accuracy in PB’s writing, but there’s beauty in what he’s saying. You see, the doctrine has to be beautiful also. It can’t be only good and true; it must be beautiful.

THE ESOTERIC MEANING Of the star is "Philosophic Man," that is, one who has travelled the complete fivefold path and brought its results into proper balance. This path consists of religious veneration, mystical meditation, rational reflection, moral re-education, and altruistic service. The esoteric meaning of the circle, when situated within the very centre of the star, is the Divine Overself-atom within the human heart. (v13, 20:1.23 and Perspectives, p. 260)

ANTHONY: Draw a five-pointed star and put a circle in the middle. The esoteric meaning of the star is "the Philosopher," symbolized by this five-pointed star. Why? Look at each one of those points. Under the auspices of the Overself, the person has been put through a program of moral re-education, mystical meditation, religious veneration, rational reflection, and altruistic service. One, two, three, four, five. The Overself atom is in the center. This five-fold path is something which is brought to completion by the radiation coming from the Overself. The completion will not take place without that. Without that higher point of view, the relativity of morals is obvious; anyone who studies any anthropology will see that. And it’s hardly likely that you’ll know what religious veneration truly is or mystical meditation unless the Overself guides you in these things.

AH: Is the suggestion that none of those things would be possible without the Overself’s grace?

ANTHONY: They’re possible to some degree, yes, but certainly not in the completed sense that he’s speaking about here: that of the philosopher whose morality is derived from within, from the heart-center. Mystical meditation will not really proceed very far unless there’s the blessing or the encouragement from your own higher Self, and likewise with the others. So very obviously, the philosopher is one who’s been taken under tutelage by the higher Self and put through this five-fold path. It has to be brought to completion, and all these things have to be balanced with one another.

THERE IS A KIND of understanding combined with feeling which is not a common one here in the West, indeed uncommon enough to seem more discoverable and less puzzling in the Asiatic regions. It is puzzling for four reasons. One is that it cannot be attributed to the intellect alone, nor to the emotional nature alone. Another is that it provides an experience so difficult to describe that it is preferable not to discuss it at all. A third is that although the most reverent it is not allied to religion. A fourth point is that it is outside any precise labelling as for instance a metaphysics or cult which could really belong to it. Yet it is neither anything new or old. It is nameless. But because there is only one way to deal with it honestly—the way of utter silence, speechless when in contact with other humans, perfectly still when in the secrecy of a closed room—we may renew the Pythagorean appellation of "philosophy" for it is truly the love of wisdom-knowledge. (v13, 20:1.129 and Perspectives, p. 253)

ANTHONY: Here we stand in the face of the Silence. Sometimes we try to grasp this by sitting outside and watching the sunset, and I tell you, reduce yourself to two-dimensional being, keep quiet, try to feel that stillness. If you do, there’s nothing you can talk about; there’s nothing there that you can say anything about. But you begin to like it, little by little, more and more.

PHILOSOPHY OVERCOMES the mystic’s fear of worldly life and the worldling’s fear of mystical life by bringing them together and reconciling their demands under the transforming light of a new synthesis. (v13, 20:1.8)

ANTHONY: And in our age that’s absolutely necessary. Never before has there been such a demand on people to combine both the spiritual and material, to stop separating them.

THOSE WHO WOULD assign philosophy the role of a leisurely pastime for a few people who have nothing better to do, are greatly mistaken. Philosophy, correctly understood, involves living as well as being. Its value is not merely intellectual, not merely to stimulate thought, but also to guide action. Its ideas and ideals are not left suspended in mid-air, as it were, unable to come down to earth in practical and practicable forms. It can be put to the test in daily living. It can be applied to all personal and social problems without exception. It shows us how to achieve a balanced existence in an unbalanced society. It is truth made workable. The study of and practice of philosophy are particularly valuable to men and women who follow certain professions, such as physicians, lawyers, and teachers, or who hold a certain social status, such as business executives, political administrators, and leaders of organizations. Those who have been placed by character or destiny or by both where their authority touches the lives of numerous others, or where their influence affects the minds of many more, who occupy positions of responsibility or superior status, will find in its principles that which will enable them to direct others wisely and in a manner conducive to the ultimate happiness of all. In the end it can only justify its name if it dynamically inspires its votaries to a wise altruistic and untiring activity, both in self-development and social development. (v13, 20:1.177 and Perspectives, p. 255)

ANTHONY: It really comes down to this: Philosophy is not only the supremely precious and the most beautiful, but also the most practical.

DB: Philosophy allows one to live in harmony with the unfoldment of the World-Idea.

ANTHONY: What could be more practical than discovering the laws that are imprinted on the cosmos by the World-Mind and working in harmony with them? That actually leads to a cessation of suffering and pain.

WE WHO HONOUR philosophy so highly cannot afford to be other than honest with ourselves. We have to acknowledge that the end of all our striving is surrender. No human being can do other than this—an utterly humble prostration, where we dissolve, lose the ego, lose ourselves—the rest is paradox and mystery. (v13, 20:5.11)

AH: Anthony, I don’t understand this quote, would you help?

ANTHONY: Well, it’s a very beautiful quote. He’s saying those of us who love philosophy, cultivate it, and understand it, are brought to wonder and awe and dissolve in that. . . . And then of course, what follows will be mysteries and paradoxes, but that would be philosophic understanding.

AH: So the we here is students of philosophy, lovers of philosophy?

ANTHONY: Those who love philosophy—that’s what philosophy is, lovers of wisdom. Those of us who love philosophy, cultivate it, and understand something about it, after a while will feel as though we are dissolving in that wonder, in that awe. It’s inevitable. You don’t even have to bring in self-abnegation, because it will happen very naturally if you truly cultivate philosophy.

KD: Is it because you’re brought out of your personal being? Is it thinking itself that draws you out, so that, for example, trying to understand metaphysical principles somehow brings you out of the personal?

ANTHONY: Yes, it brings you out of the personal. You don’t live in a world of action and reaction. You get to understand the fact that is, and not your reactions to it. There’s a fact, there’s a what, and you try to understand that, and that means you have to eliminate your reactions to it. If you eliminate your reactions to it, you eliminate the whole dualistic process of thinking, you get into the depths of philosophy, and then the wonder and the awe of it all begins to dawn on you.

KD: Why?

ANTHONY: Well, when you get rid of the little ego, then the rest comes in. The rest can’t come in unless you get rid of the ego. You get some of that now and then, don’t you? When you are listening very intensely to a piece of music there is no choice but to deny the self, so that, through identity, you might properly appreciate that music. In a similar way, to properly appreciate the wonder of the ideas, some of the things that are explained in philosophy, it is necessary to get rid of your I. And in philosophy, if a person is truly in love with the things that are being understood, it’s inevitable that an abnegation of the [ego-]self will take place. And all of those will eventually lead to that self-abnegation. You can’t get into philosophy if you’re full of yourself.

TRUTH EXISTED before the churches began to spire their way upwards into the sky, and it will continue to exist after the last academy of philosophy has been battered down. Nothing can still the primal need of it in man. Priesthoods can be exterminated until not one vestige is left in the land; mystic hermitages can be broken until they are but dust; philosophical books can be burnt out of existence by culture-hating tyrants, yet this subterranean sense in man which demands the understanding of its own existence will one day rise again with an urgent claim and create a new expression of itself. (v13, 20:5.262 and Perspectives, p. 254)

ANTHONY: Some of his notes are really statements. This is what the truth is, period. No commentary is going to change it or explain it. Discussion isn’t necessary, a simple recognition is enough.

A SCHOOL SHOULD EXIST not only to teach but also to investigate, not to formulate prematurely a finalized system but to remain creative, to go on testing theories by applying them and validating ideas by experience. (v2, 1:4.111 and Perspectives, p. 12)

ANTHONY: This is why we do not restrict ourselves to any one school. It is not possible to come down with a final chapter on answering a question. When you understand philosophy, you understand that that can’t be done.

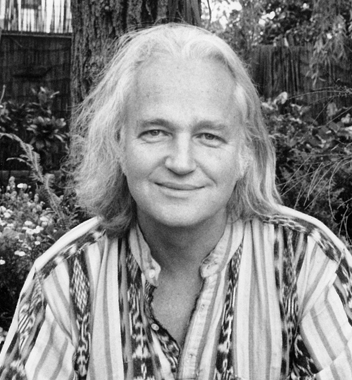

From the introduction to Anthony's book, Looking into Mind

For hundreds of us who met him in the 1960s and 1970s, Anthony Damiani (1922–1984) was a man of many facets, any one of which would have made him remarkable. But first and foremost he was a man—a vital, passionate, kind, and dynamic human being who revered life by living sincerely. He saw the meanings embedded in each person’s experience as lines of a primordial scripture that one is born to embrace and understand—with and as one’s whole being. His genius lay in piercing the secular veneer, uncovering these meanings, and awakening the heart to an awareness of the sacred song at their core. This was a process of giving birth to truth, not as a conceptual exercise but as an act of love, an exquisite expression of the proper relation between a soul and its source.

Anthony’s mental energies were volcanic, as though surging upward from the very core of what compelled his attention. His burning desire to experience, understand, and express the undeniable significances of being human led him through a variety of life-experiences and specialized fields of study. When he discussed spiritual philosophy, he often seemed incandescent with enthusiasm about the value of what he had discovered and could share. But he had little regard for pretension either in himself or in others. While his generous spirit always encouraged us to be ourselves and supported each of us wholeheartedly in times of inner or outer personal difficulty, his penetrating gaze or mischievous humor soon deflated us when we became too puffed up about anything we thought we had learned. On first impression, he was the very antithesis of the conventional image of a spiritual teacher.

* * * * *

Anthony Damiani was born in 1922 into an Italian immigrant family on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and grew up in Brooklyn. As a child and young man, he suffered the fate of many a potentially deep thinker: his long silences were interpreted by teachers as indicating a learning deficiency and he was often placed among “slow learners” in his classes. Even then, he could not settle for surface appearances, pat answers to questions that were themselves too shallow, and read Plato secretly. His artistic nature first expressed itself in drawings and paintings that showed extraordinary sensitivity and perceptiveness.

Anthony spoke of two particular events from his youth that awakened him to the possibility of a higher life. One was when he first heard Schubert’s Quintet in C. He said, “Once I heard that piece, I knew there was a heaven.” The piece awakened in him a lifelong passion for inspired music and kindled a serious aspiration to become a classical pianist. The second came when he was watching a newsreel from India at a Brooklyn movie house. In the background of the main scene, he saw a yogi meditating on the sun. The image burned into his mind, and from that time forward learning the art of meditation became one of his main preoccupations.

He married his childhood sweetheart, and together they started a family which eventually included six sons. Though they had little money, he often spoke fondly in later life of how happy they were in their first Brooklyn flat. They had few domestic furnishings, having chosen instead to spend most of their earnings on inspiring books and a highly diversified collection of fine music.

Anthony held a variety of jobs, often two at a time. They included working as a waiter, then as a maitre d’hôtel, spending nine years as a longshoreman on the New York docks, and managing a major New York City bookstore. He also took many classes in philosophy at Brooklyn College, CCNY, and the New School for Social Research, though he chose not to earn an academic degree. As his family grew in size, it became increasingly difficult for him to find the time and quiet to continue his self-directed studies in philosophy and mysticism while earning enough money to support the family. His solution was to start working nights as a token seller in a relatively slow section of the New York subway system; there he was able to pass the night immersed in the thoughts of Plotinus, Buddha, Shankara, Patanjali and many other great sages—and earn money at the same time.

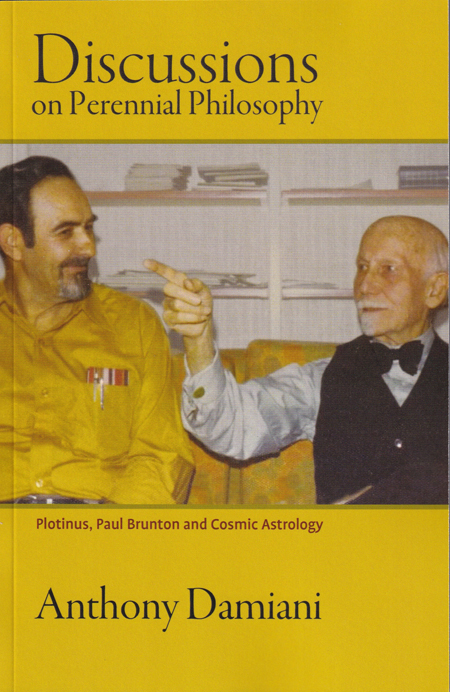

Possibly the most important single event in Anthony’s development was when he met the British philosopher Paul Brunton. From the day of their first meeting, Anthony felt that he had found his destined teacher. He was profoundly inspired by Paul Brunton’s ability to integrate mystical philosophy and modern science into an approach to self-realization especially suited for the modern mind, and to express his findings in clear English. The breadth and depth of Paul Brunton’s research, application, and personal achievement catalyzed Anthony’s own desire for a comprehensive updating and philosophic synthesis of the wisdom—practical and spiritual—of both East and West.

But Paul Brunton took no students formally, describing himself as “a writer and researcher, with some experience in these matters . . . that is all.” Anthony often had to be content with limited outer contact, making himself of service when appropriate, and acting primarily on the inspiration he drew from within himself from Paul Brunton’s example and occasional explicit instructions. Nonetheless, a unique and very special relationship developed through the years between these two genuinely remarkable men as Anthony learned that the best way to venerate one’s spiritual teacher is to work sincerely at becoming one’s own best self. In his “retirement,” Paul Brunton praised Anthony highly and often recommended him to people seeking help with their studies and personal development.

Shortly after meeting Paul Brunton, Anthony resolved to give up his study of the piano and focus his aspirations on meditation and philosophic studies. Listening to inspired music remained, however, an essential part of his inner development. Because music was for him more transparent than words as a vehicle of spiritual discovery, he often discovered his next guiding intuition through a piece of music, and integrated it deeply into his feelings before trying to approach it in an intellectual way. This practice was of such value to him that it later became an integral part of his teaching method.

The next major contribution to Anthony’s development came through a detailed study of the great Neoplatonic sage Plotinus. In Plotinus’ Enneads, Anthony found what he considered the most comprehensive extant statement of the metaphysical aspects of perennial philosophy, a teaching that complemented his understanding of Paul Brunton’s writings and held out the promise of answering his remaining questions. His studies in Plotinus and related Platonic teachings continued for the rest of his life and formed the foundation of his own most important creative work.

In 1963, the Damiani family moved out of New York City to the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York. One moving van contained their domestic possessions. Another was filled with books on philosophy and mysticism. Throughout his years of working in bookstores, Anthony had always taken first choice on any new or rare esoteric books. His collection was astonishing not only for its intrinsic breadth and quality, but also for the extensive underscoring and marginalia that testified to his thousands of hours of intensive study.

Upstate, Anthony took a night job as a toll-taker on the New York Thruway, a job that like his subway work allowed time to study. In 1967, he suffered a severe heart attack and experienced death. He said later that during those moments when he thought he was leaving life behind, his heart overflowed with love and tenderness for all living things. Though he had previously envisaged his new home as primarily a hermitage for retreat and study, harvesting the fruits of contemplation in relative solitude soon became unthinkable.

Later that year, with the help of his son Stephen, he rented a small storefront in Ithaca, New York, and filled its shelves primarily with his own books. He kept his night job on the Thruway and spent most of his days in the store. This store, with a statue of the Buddha in the window, attracted inquisitive students and some teachers from Ithaca College and Cornell University, as well as many other people who just happened to be passing through town. The man inside soon legitimized and catalyzed our deepest spiritual urges.

In those days, Anthony was a dynamo. He slept only a few hours between getting off his night job at seven in the morning and leaving for the store shortly after noon. At first, only a steady trickle of people came to buy or borrow books and then returned to discuss them with Anthony. Soon, the number of us eager to discuss spiritual issues or learn the art of meditation with him grew large enough that informal evening classes began in the back room of the store. Anthony often wore his toll-taker’s uniform while giving these classes, so that he could rush out at the last minute to drive fifty miles to make his 11:00 night shift on the Thruway. Within two years, his animated classes on Jung’s psychology, Hinduism, Buddhism, Christian Scholasticism, Platonism, Paul Brunton’s writings, and an exciting new approach to a genuinely spiritual astrology had attracted more people than the store could hold.

In 1972, Anthony and his wife Ella May donated five acres of their family land to what became the Wisdom’s Goldenrod Center for Philosophic Studies, and we built its first building ourselves. Through the next seven years, we built three more buildings as our needs grew organically, including an extensive library. The library was dedicated in 1979 by His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama of Tibet, who spent three days with the Wisdom’s Goldenrod community on his first U.S. tour. The Dalai Lama praised Anthony’s activities at Wisdom’s Goldenrod as an excellent balance of the spiritual and the practical, and he spoke of Anthony himself as “a truly great man.”

Throughout all the developments that took place after he opened the bookstore, Anthony took great pains to present himself as a fellow student, not a teacher, and he always taught without salary or payment of any kind. But after the Dalai Lama’s visit, it became obvious even to Anthony that he had become, even if unwittingly, a spiritual teacher.

* * * * * *

Anthony Damiani died in October, 1984. He left behind a variety of materials that merit publication, including numerous essays, a nearly completed book on philosophical symbolism, and a wide selection of recorded classes on how various spiritual issues are treated in different philosophical and religious traditions. The points he declined to pursue in detail in the Swedish discussions are developed in forthcoming* material being prepared for publication here at Wisdom’s Goldenrod. We chose the conversations in this book as the most widely accessible introduction to his work.

Special thanks from each of us go to the Damiani family, not only for their help in preparing this book and for granting us the rights to publish it, but much more importantly for sharing Anthony and themselves with us through all these years. Together we send this book into the world with the hope of sharing Anthony’s inspiration toward individual integrity and global philosophic understanding. “If people who claim to be interested in spirituality can’t find a harmony and make peace among themselves,” he used to ask, “how will the politicians ever make peace?”

Paul Cash

Director

Larson Publications

*Editor’s note: Since this introduction was written, three more publications have come forth: Standing in Your Own Way, Living Wisdom, and Anthony's master work: Astronoesis.

Book Details

This book delivers, concisely and accessibly, the essence of the Paul Brunton / Anthony Damiani school of spiritual awakening and practice. It offers what many consider a satisfying vision of mature spirituality: a perspective that honors reason and beauty, cultivates intuition and mystical experience, fosters reverence and true prayer, and inspires practical action and morality. Its approach to self and world is as broad and deep as life itself, articulating the unique values of each of life’s many aspects.

As Robert Sardello wrote in his Parabola review: "People are starving to find meaning. But the one path that is open to the modern person, the spiritual path of thinking, is neglected . . . because there are not many individuals around who are dedicated to this path, because thinking has been captured by the forces of hardness. Perhaps this marvelous, this exciting, this truly tremendous book will give a new context for cognition—full of soul which reaches out to touch spirit. Wisdom can be approached only through the path of thinking-feeling, and we must be deeply grateful to Anthony Damiani for showing us the way again."

Anthony Damiani (1922–1984) founded the Wisdom’s Goldenrod Center for Philosophic Studies in 1972. Living Wisdom is an edited transcript of his commentaries and elaborations on the “What Is Philosophy?” section of Paul Brunton’s Notebooks.

See other tabs on this page for selections from the text and information about Anthony Damiani.

Also by Anthony Damiani from Larson Publications:

Looking into Mind

Standing in Your Own Way

Astronoesis

"Those of us who love philosophy, cultivate it, and understand something about it, after a while will feel as though we are dissolving in that wonder, in that awe. It’s inevitable. You don’t even have to bring in self-abnegation, because it will happen very naturally if you truly cultivate philosophy." —Anthony Damiani

"Anthony Damiani is a philosophic genius . . . a fully qualified philosophic teacher." —Paul Brunton

"Anthony Damiani . . . a passionate and inspired philosopher." —Georg Feuerstein

"Anthony Damiani [was] a truly great man . . . one of my closest spiritual brothers . . . His work combines and balances the best of the spiritual and the material." —H.H. Dalai Lama

"People are starving to find meaning. But the one path that is open to the modern person, the spiritual path of thinking, is neglected . . . because there are not many individuals around who are dedicated to this path, because thinking has been captured by the forces of hardness. Perhaps this marvelous, this exciting, this truly tremendous book will give a new context for cognition--full of soul which reaches out to touch spirit. Wisdom can be approached only through the path of thinking-feeling, and we must be deeply grateful to Anthony Damiani for showing us the way again." —Robert Sardello, in Parabola

"Damiani was a visionary genius intent on peering into the heart of reality, making personal acquaintance with 'the wisdom-knowledge that sustains the cosmos.'"—The Mountain Astrologer

Contents

Editors’ Foreword

1. Introduction to the Philosophic Life

2. Philosophic Development

Stages of Development

The World-Mind Teaches You

Development and Balance of Knowing, Willing, and Feeling Leads to Insight

3. Enlightenment

Insight, Intuition, and Psyche

Insight and Manifestation

The Double Knower

Philosophic vs. Mystical Realization

Permanent Enlightenment vs. Temporary States

4. What a Philosopher Is

Appendix: Insight and Understanding

Introduction to the Philosophic Life

IT MAY BE ASKED why I insist on using the word "philosophy" as a self-sufficient name without prefixing it by some descriptive term or person’s name when it has held different meanings in different centuries, or been associated with different points of view ranging from the most materialistic to the most spiritualist. The question is well asked, although the answer may not be quite satisfactory. I do so because I want to restore this word to its ancient dignity. I want it used for the highest kind of insight into the Truth of things, which means into the Truth of the unique Reality. I want the philosopher to be equated with the sage, the man [sic] who not only knows this Truth, has this insight, and experiences this Reality in meditation, but also, although in a modified form, in action amid the world’s turmoil. (v13, 20:1.127 and Perspectives, p. 250)

ANTHONY: PB is not going to call you a philosopher if you haven’t experienced the higher states of consciousness. A theoretician or metaphysician who hasn’t experienced these states is not a philosopher. That’s the one distinction he’s making here.

IT IS PERHAPS the amplitude and symmetry of the philosophic approach which make it so completely satisfying. For this is the only approach which honours reason and appreciates beauty, cultivates intuition and respects mystical experience, fosters reverence and teaches true prayer, enjoins action and promotes morality. It is the spiritual life fully grown. (v13, 20:1.22 and Perspectives, p. 261)

ANTHONY: Philosophy is broad-based, as big as life itself. It finds proper due for all the different aspects in life. It finds their proper evaluation or their proper place.

There’s not only precision and accuracy in PB’s writing, but there’s beauty in what he’s saying. You see, the doctrine has to be beautiful also. It can’t be only good and true; it must be beautiful.

THE ESOTERIC MEANING Of the star is "Philosophic Man," that is, one who has travelled the complete fivefold path and brought its results into proper balance. This path consists of religious veneration, mystical meditation, rational reflection, moral re-education, and altruistic service. The esoteric meaning of the circle, when situated within the very centre of the star, is the Divine Overself-atom within the human heart. (v13, 20:1.23 and Perspectives, p. 260)

ANTHONY: Draw a five-pointed star and put a circle in the middle. The esoteric meaning of the star is "the Philosopher," symbolized by this five-pointed star. Why? Look at each one of those points. Under the auspices of the Overself, the person has been put through a program of moral re-education, mystical meditation, religious veneration, rational reflection, and altruistic service. One, two, three, four, five. The Overself atom is in the center. This five-fold path is something which is brought to completion by the radiation coming from the Overself. The completion will not take place without that. Without that higher point of view, the relativity of morals is obvious; anyone who studies any anthropology will see that. And it’s hardly likely that you’ll know what religious veneration truly is or mystical meditation unless the Overself guides you in these things.

AH: Is the suggestion that none of those things would be possible without the Overself’s grace?

ANTHONY: They’re possible to some degree, yes, but certainly not in the completed sense that he’s speaking about here: that of the philosopher whose morality is derived from within, from the heart-center. Mystical meditation will not really proceed very far unless there’s the blessing or the encouragement from your own higher Self, and likewise with the others. So very obviously, the philosopher is one who’s been taken under tutelage by the higher Self and put through this five-fold path. It has to be brought to completion, and all these things have to be balanced with one another.

THERE IS A KIND of understanding combined with feeling which is not a common one here in the West, indeed uncommon enough to seem more discoverable and less puzzling in the Asiatic regions. It is puzzling for four reasons. One is that it cannot be attributed to the intellect alone, nor to the emotional nature alone. Another is that it provides an experience so difficult to describe that it is preferable not to discuss it at all. A third is that although the most reverent it is not allied to religion. A fourth point is that it is outside any precise labelling as for instance a metaphysics or cult which could really belong to it. Yet it is neither anything new or old. It is nameless. But because there is only one way to deal with it honestly—the way of utter silence, speechless when in contact with other humans, perfectly still when in the secrecy of a closed room—we may renew the Pythagorean appellation of "philosophy" for it is truly the love of wisdom-knowledge. (v13, 20:1.129 and Perspectives, p. 253)

ANTHONY: Here we stand in the face of the Silence. Sometimes we try to grasp this by sitting outside and watching the sunset, and I tell you, reduce yourself to two-dimensional being, keep quiet, try to feel that stillness. If you do, there’s nothing you can talk about; there’s nothing there that you can say anything about. But you begin to like it, little by little, more and more.

PHILOSOPHY OVERCOMES the mystic’s fear of worldly life and the worldling’s fear of mystical life by bringing them together and reconciling their demands under the transforming light of a new synthesis. (v13, 20:1.8)

ANTHONY: And in our age that’s absolutely necessary. Never before has there been such a demand on people to combine both the spiritual and material, to stop separating them.

THOSE WHO WOULD assign philosophy the role of a leisurely pastime for a few people who have nothing better to do, are greatly mistaken. Philosophy, correctly understood, involves living as well as being. Its value is not merely intellectual, not merely to stimulate thought, but also to guide action. Its ideas and ideals are not left suspended in mid-air, as it were, unable to come down to earth in practical and practicable forms. It can be put to the test in daily living. It can be applied to all personal and social problems without exception. It shows us how to achieve a balanced existence in an unbalanced society. It is truth made workable. The study of and practice of philosophy are particularly valuable to men and women who follow certain professions, such as physicians, lawyers, and teachers, or who hold a certain social status, such as business executives, political administrators, and leaders of organizations. Those who have been placed by character or destiny or by both where their authority touches the lives of numerous others, or where their influence affects the minds of many more, who occupy positions of responsibility or superior status, will find in its principles that which will enable them to direct others wisely and in a manner conducive to the ultimate happiness of all. In the end it can only justify its name if it dynamically inspires its votaries to a wise altruistic and untiring activity, both in self-development and social development. (v13, 20:1.177 and Perspectives, p. 255)

ANTHONY: It really comes down to this: Philosophy is not only the supremely precious and the most beautiful, but also the most practical.

DB: Philosophy allows one to live in harmony with the unfoldment of the World-Idea.

ANTHONY: What could be more practical than discovering the laws that are imprinted on the cosmos by the World-Mind and working in harmony with them? That actually leads to a cessation of suffering and pain.

WE WHO HONOUR philosophy so highly cannot afford to be other than honest with ourselves. We have to acknowledge that the end of all our striving is surrender. No human being can do other than this—an utterly humble prostration, where we dissolve, lose the ego, lose ourselves—the rest is paradox and mystery. (v13, 20:5.11)

AH: Anthony, I don’t understand this quote, would you help?

ANTHONY: Well, it’s a very beautiful quote. He’s saying those of us who love philosophy, cultivate it, and understand it, are brought to wonder and awe and dissolve in that. . . . And then of course, what follows will be mysteries and paradoxes, but that would be philosophic understanding.

AH: So the we here is students of philosophy, lovers of philosophy?

ANTHONY: Those who love philosophy—that’s what philosophy is, lovers of wisdom. Those of us who love philosophy, cultivate it, and understand something about it, after a while will feel as though we are dissolving in that wonder, in that awe. It’s inevitable. You don’t even have to bring in self-abnegation, because it will happen very naturally if you truly cultivate philosophy.

KD: Is it because you’re brought out of your personal being? Is it thinking itself that draws you out, so that, for example, trying to understand metaphysical principles somehow brings you out of the personal?

ANTHONY: Yes, it brings you out of the personal. You don’t live in a world of action and reaction. You get to understand the fact that is, and not your reactions to it. There’s a fact, there’s a what, and you try to understand that, and that means you have to eliminate your reactions to it. If you eliminate your reactions to it, you eliminate the whole dualistic process of thinking, you get into the depths of philosophy, and then the wonder and the awe of it all begins to dawn on you.

KD: Why?

ANTHONY: Well, when you get rid of the little ego, then the rest comes in. The rest can’t come in unless you get rid of the ego. You get some of that now and then, don’t you? When you are listening very intensely to a piece of music there is no choice but to deny the self, so that, through identity, you might properly appreciate that music. In a similar way, to properly appreciate the wonder of the ideas, some of the things that are explained in philosophy, it is necessary to get rid of your I. And in philosophy, if a person is truly in love with the things that are being understood, it’s inevitable that an abnegation of the [ego-]self will take place. And all of those will eventually lead to that self-abnegation. You can’t get into philosophy if you’re full of yourself.

TRUTH EXISTED before the churches began to spire their way upwards into the sky, and it will continue to exist after the last academy of philosophy has been battered down. Nothing can still the primal need of it in man. Priesthoods can be exterminated until not one vestige is left in the land; mystic hermitages can be broken until they are but dust; philosophical books can be burnt out of existence by culture-hating tyrants, yet this subterranean sense in man which demands the understanding of its own existence will one day rise again with an urgent claim and create a new expression of itself. (v13, 20:5.262 and Perspectives, p. 254)

ANTHONY: Some of his notes are really statements. This is what the truth is, period. No commentary is going to change it or explain it. Discussion isn’t necessary, a simple recognition is enough.

A SCHOOL SHOULD EXIST not only to teach but also to investigate, not to formulate prematurely a finalized system but to remain creative, to go on testing theories by applying them and validating ideas by experience. (v2, 1:4.111 and Perspectives, p. 12)

ANTHONY: This is why we do not restrict ourselves to any one school. It is not possible to come down with a final chapter on answering a question. When you understand philosophy, you understand that that can’t be done.

About Anthony Damiani

From the introduction to Anthony's book, Looking into Mind

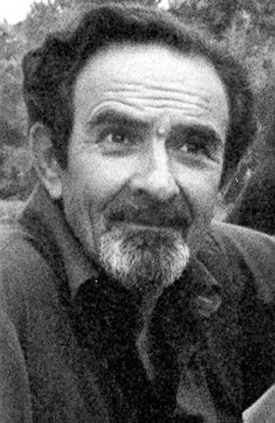

For hundreds of us who met him in the 1960s and 1970s, Anthony Damiani (1922–1984) was a man of many facets, any one of which would have made him remarkable. But first and foremost he was a man—a vital, passionate, kind, and dynamic human being who revered life by living sincerely. He saw the meanings embedded in each person’s experience as lines of a primordial scripture that one is born to embrace and understand—with and as one’s whole being. His genius lay in piercing the secular veneer, uncovering these meanings, and awakening the heart to an awareness of the sacred song at their core. This was a process of giving birth to truth, not as a conceptual exercise but as an act of love, an exquisite expression of the proper relation between a soul and its source.

Anthony’s mental energies were volcanic, as though surging upward from the very core of what compelled his attention. His burning desire to experience, understand, and express the undeniable significances of being human led him through a variety of life-experiences and specialized fields of study. When he discussed spiritual philosophy, he often seemed incandescent with enthusiasm about the value of what he had discovered and could share. But he had little regard for pretension either in himself or in others. While his generous spirit always encouraged us to be ourselves and supported each of us wholeheartedly in times of inner or outer personal difficulty, his penetrating gaze or mischievous humor soon deflated us when we became too puffed up about anything we thought we had learned. On first impression, he was the very antithesis of the conventional image of a spiritual teacher.

* * * * *

Anthony Damiani was born in 1922 into an Italian immigrant family on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, and grew up in Brooklyn. As a child and young man, he suffered the fate of many a potentially deep thinker: his long silences were interpreted by teachers as indicating a learning deficiency and he was often placed among “slow learners” in his classes. Even then, he could not settle for surface appearances, pat answers to questions that were themselves too shallow, and read Plato secretly. His artistic nature first expressed itself in drawings and paintings that showed extraordinary sensitivity and perceptiveness.

Anthony spoke of two particular events from his youth that awakened him to the possibility of a higher life. One was when he first heard Schubert’s Quintet in C. He said, “Once I heard that piece, I knew there was a heaven.” The piece awakened in him a lifelong passion for inspired music and kindled a serious aspiration to become a classical pianist. The second came when he was watching a newsreel from India at a Brooklyn movie house. In the background of the main scene, he saw a yogi meditating on the sun. The image burned into his mind, and from that time forward learning the art of meditation became one of his main preoccupations.

He married his childhood sweetheart, and together they started a family which eventually included six sons. Though they had little money, he often spoke fondly in later life of how happy they were in their first Brooklyn flat. They had few domestic furnishings, having chosen instead to spend most of their earnings on inspiring books and a highly diversified collection of fine music.

Anthony held a variety of jobs, often two at a time. They included working as a waiter, then as a maitre d’hôtel, spending nine years as a longshoreman on the New York docks, and managing a major New York City bookstore. He also took many classes in philosophy at Brooklyn College, CCNY, and the New School for Social Research, though he chose not to earn an academic degree. As his family grew in size, it became increasingly difficult for him to find the time and quiet to continue his self-directed studies in philosophy and mysticism while earning enough money to support the family. His solution was to start working nights as a token seller in a relatively slow section of the New York subway system; there he was able to pass the night immersed in the thoughts of Plotinus, Buddha, Shankara, Patanjali and many other great sages—and earn money at the same time.

Possibly the most important single event in Anthony’s development was when he met the British philosopher Paul Brunton. From the day of their first meeting, Anthony felt that he had found his destined teacher. He was profoundly inspired by Paul Brunton’s ability to integrate mystical philosophy and modern science into an approach to self-realization especially suited for the modern mind, and to express his findings in clear English. The breadth and depth of Paul Brunton’s research, application, and personal achievement catalyzed Anthony’s own desire for a comprehensive updating and philosophic synthesis of the wisdom—practical and spiritual—of both East and West.

But Paul Brunton took no students formally, describing himself as “a writer and researcher, with some experience in these matters . . . that is all.” Anthony often had to be content with limited outer contact, making himself of service when appropriate, and acting primarily on the inspiration he drew from within himself from Paul Brunton’s example and occasional explicit instructions. Nonetheless, a unique and very special relationship developed through the years between these two genuinely remarkable men as Anthony learned that the best way to venerate one’s spiritual teacher is to work sincerely at becoming one’s own best self. In his “retirement,” Paul Brunton praised Anthony highly and often recommended him to people seeking help with their studies and personal development.

Shortly after meeting Paul Brunton, Anthony resolved to give up his study of the piano and focus his aspirations on meditation and philosophic studies. Listening to inspired music remained, however, an essential part of his inner development. Because music was for him more transparent than words as a vehicle of spiritual discovery, he often discovered his next guiding intuition through a piece of music, and integrated it deeply into his feelings before trying to approach it in an intellectual way. This practice was of such value to him that it later became an integral part of his teaching method.

The next major contribution to Anthony’s development came through a detailed study of the great Neoplatonic sage Plotinus. In Plotinus’ Enneads, Anthony found what he considered the most comprehensive extant statement of the metaphysical aspects of perennial philosophy, a teaching that complemented his understanding of Paul Brunton’s writings and held out the promise of answering his remaining questions. His studies in Plotinus and related Platonic teachings continued for the rest of his life and formed the foundation of his own most important creative work.

In 1963, the Damiani family moved out of New York City to the Finger Lakes region of upstate New York. One moving van contained their domestic possessions. Another was filled with books on philosophy and mysticism. Throughout his years of working in bookstores, Anthony had always taken first choice on any new or rare esoteric books. His collection was astonishing not only for its intrinsic breadth and quality, but also for the extensive underscoring and marginalia that testified to his thousands of hours of intensive study.

Upstate, Anthony took a night job as a toll-taker on the New York Thruway, a job that like his subway work allowed time to study. In 1967, he suffered a severe heart attack and experienced death. He said later that during those moments when he thought he was leaving life behind, his heart overflowed with love and tenderness for all living things. Though he had previously envisaged his new home as primarily a hermitage for retreat and study, harvesting the fruits of contemplation in relative solitude soon became unthinkable.

Later that year, with the help of his son Stephen, he rented a small storefront in Ithaca, New York, and filled its shelves primarily with his own books. He kept his night job on the Thruway and spent most of his days in the store. This store, with a statue of the Buddha in the window, attracted inquisitive students and some teachers from Ithaca College and Cornell University, as well as many other people who just happened to be passing through town. The man inside soon legitimized and catalyzed our deepest spiritual urges.

In those days, Anthony was a dynamo. He slept only a few hours between getting off his night job at seven in the morning and leaving for the store shortly after noon. At first, only a steady trickle of people came to buy or borrow books and then returned to discuss them with Anthony. Soon, the number of us eager to discuss spiritual issues or learn the art of meditation with him grew large enough that informal evening classes began in the back room of the store. Anthony often wore his toll-taker’s uniform while giving these classes, so that he could rush out at the last minute to drive fifty miles to make his 11:00 night shift on the Thruway. Within two years, his animated classes on Jung’s psychology, Hinduism, Buddhism, Christian Scholasticism, Platonism, Paul Brunton’s writings, and an exciting new approach to a genuinely spiritual astrology had attracted more people than the store could hold.

In 1972, Anthony and his wife Ella May donated five acres of their family land to what became the Wisdom’s Goldenrod Center for Philosophic Studies, and we built its first building ourselves. Through the next seven years, we built three more buildings as our needs grew organically, including an extensive library. The library was dedicated in 1979 by His Holiness the XIVth Dalai Lama of Tibet, who spent three days with the Wisdom’s Goldenrod community on his first U.S. tour. The Dalai Lama praised Anthony’s activities at Wisdom’s Goldenrod as an excellent balance of the spiritual and the practical, and he spoke of Anthony himself as “a truly great man.”

Throughout all the developments that took place after he opened the bookstore, Anthony took great pains to present himself as a fellow student, not a teacher, and he always taught without salary or payment of any kind. But after the Dalai Lama’s visit, it became obvious even to Anthony that he had become, even if unwittingly, a spiritual teacher.

* * * * * *

Anthony Damiani died in October, 1984. He left behind a variety of materials that merit publication, including numerous essays, a nearly completed book on philosophical symbolism, and a wide selection of recorded classes on how various spiritual issues are treated in different philosophical and religious traditions. The points he declined to pursue in detail in the Swedish discussions are developed in forthcoming* material being prepared for publication here at Wisdom’s Goldenrod. We chose the conversations in this book as the most widely accessible introduction to his work.

Special thanks from each of us go to the Damiani family, not only for their help in preparing this book and for granting us the rights to publish it, but much more importantly for sharing Anthony and themselves with us through all these years. Together we send this book into the world with the hope of sharing Anthony’s inspiration toward individual integrity and global philosophic understanding. “If people who claim to be interested in spirituality can’t find a harmony and make peace among themselves,” he used to ask, “how will the politicians ever make peace?”

Paul Cash

Director

Larson Publications

*Editor’s note: Since this introduction was written, three more publications have come forth: Standing in Your Own Way, Living Wisdom, and Anthony's master work: Astronoesis.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)