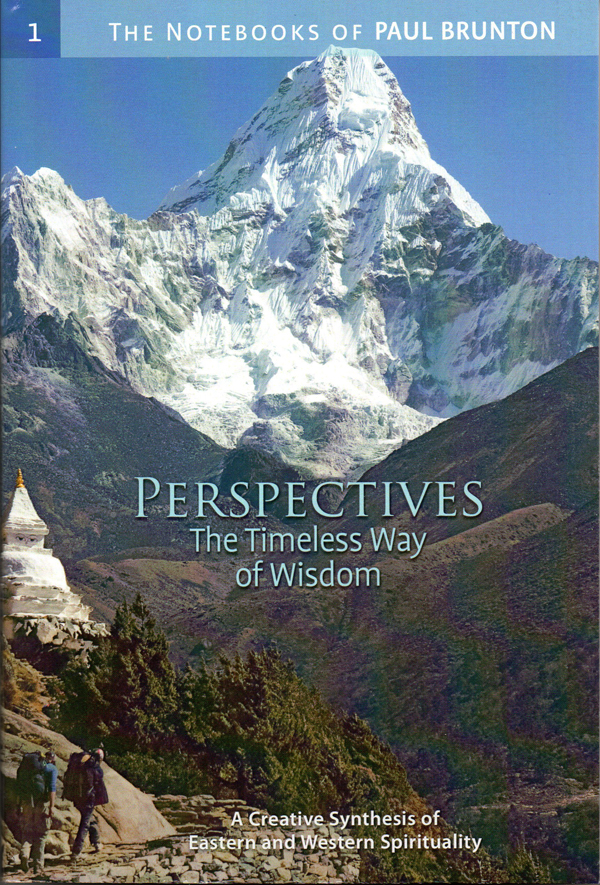

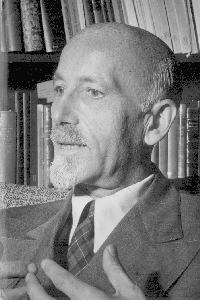

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton volume 1

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton Volume 1, Perspectives: The Timeless Way of Wisdom By Paul Brunton

Retail/cover price: $22.95

Our price : $18.36

(You save $4.59!)

About this book:

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton volume 1

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton Volume 1, Perspectives: The Timeless Way of Wisdom

by Paul Brunton

This is where most people like to start reading Paul Brunton's astonishing Notebooks.

Subjects: Spirituality, Inspiration

5.75 x 8.5, paperback

(hardcover is out of stock)

424 pages

ISBN 10: 0-943914-12-4

ISBN 13: 978-0-943914-12-1

Book Details

This is a great place to start reading Paul Brunton's posthumously published Notebooks — an uplifting, enlightening, and representative survey of virtually every aspect of spiritual awakening and stage of practice. Each of its 28 chapters samples one of the 28 “categories” into which Paul Brunton filed his writings. Topics included are:

- meditation

- the body

- emotions and ethics

- the intellect

- the ego

- world crisis

- the arts in culture

- psychic experiences

- philosophy

- the Overself

- cosmology

- the Absolute

- and much more (see table of contents)

Subsequent volumes in the series focus in detail on individual categories in the 1–28 outline structure.

See tabs below for a full table of contents, the editors’ introduction, some samples from the text, and selected highlights from this noteworthy volume’s many favorable reviews.

1. THE QUEST

Its choice—Independent path—Organized groups—Self-development—Student/teacher

2. PRACTICES FOR THE QUEST

Ant's long path—Work on oneself

3. RELAX AND RETREAT

Intermittent pauses—Tension and pressures—Relax body, breath, and mind—Retreat centres—Solitude—Nature

appreciation—Sunset contemplation

4. ELEMENTARY MEDITATION

Place and conditions—Wandering thoughts—Practice concentrated attention—Meditative thinking—Visualized images

—Mantrams—Symbols—Affirmations and suggestions

5. THE BODY

Hygiene and cleansings—Food—Exercises and postures—Breathings—Sex: importance, influence, effects

6. EMOTIONS AND ETHICS

Uplift character—Re-educate feelings—Discipline emotions—Purify passions—Refinement and courtesy—Avoid

fanaticism

7. THE INTELLECT

Nature—Services—Development—Semantic training—Science—Metaphysics—Abstract thinking

8. THE EGO

What am I—The I-thought—The psyche

9. FROM BIRTH TO REBIRTH

Experience of dying—After death—Rebirth—Past tendencies --Destiny—Freedom—Astrology

10. HEALING OF THE SELF

Karma, connection with health—Life-force in health and sickness—Drugs and drink in mind-body relationship—Etheric

and astral bodies in health and sickness—Mental disorders—Psychology and psychoanalysis

11. THE NEGATIVES

Nature—Roots in ego—Presence in the world—In thoughts, feelings, and violent passions—Their visible and invisible

harm

12. REFLECTIONS

13. HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Situation—Events—Lessons—World Crisis—Reflections in old age—Reflections on youth

14. THE ARTS IN CULTURE

Appreciation—Creativity—Genius—Art experience and mysticism—Reflections on pictures, sculpture, literature,

poetry, music

15. THE ORIENT

Meetings with the Occident—Oriental people, places, practices—Sayings of philosophers—Schools of philosophy

16. THE SENSITIVES

Psychic and auric experiences—Intuitions—Sects and cults

17. THE RELIGIOUS URGE

Origin—Recognition—Manifestations—Traditional and less known religions—Connection with philosophy

18. THE REVERENTIAL LIFE

Prayer—Devotion—Worship—Humility—Surrender—Grace: real and imagined

19. THE REIGN OF RELATIVITY

Consciousness is relative—Dream, sleep, and wakefulness—Time as past, present, and future—Space

—Twofold standpoint—Void as metaphysical fact

20. WHAT IS PHILOSOPHY?

Definition—Completeness—Balance—Fulfillment in man

21. MENTALISM

Mind and the five senses—World as mental experience—Mentalism is key to the spiritual world

22. INSPIRATION AND THE OVERSELF

Intuition the beginning—Inspiration the completion—Its presence—Glimpses

23. ADVANCED CONTEMPLATION

Ant's long path—Bird's direct path—Exercises for practice—Contemplative stillness—”Why Buddha smiled”—Heavenly

Way exercise—Serpent's Path exercise—Void as contemplative experience

24. THE PEACE WITHIN YOU

Be calm—Practise detachment—Seek the deeper Stillness

25. WORLD-MIND IN INDIVIDUAL MIND

Their meeting and interchange—Enlightenment which stays—Saints and sages

26. THE WORLD-IDEA

Divine order of the universe—Change as universal activity—Polarities, complementaries, and dualities of

the universe—True idea of man

27. WORLD MIND

God as the Supreme Individual—God as Mind-in-activity—As Solar Logos

28. THE ALONE

Mind-in-Itself—The Unique Mind—As Absolute

“. . . a veritable treasure-trove of philosophic-spiritual wisdom.” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

“. . . sensible and compelling. His work can stand beside that of such East-West bridges as Merton, Huxley, Suzuki, Watts, and Radhakrishnan. It should appeal to anyone concerned personally and academically with issues of spirituality.” —Choice

“Vigorous, clear-minded and independent . . . a synthesis of Eastern mysticism and Western rationality. . . A rich volume.” —Library Journal

“. . . a great gift to us Westerners who are seeking the spiritual.” —Charles T. Tart

“A person of rare intelligence. . . thoroughly alive, and whole in the most significant, 'holy' sense of the word.” —Yoga Journal

For more reviews of the Notebooks series, click here

Editors' Introduction

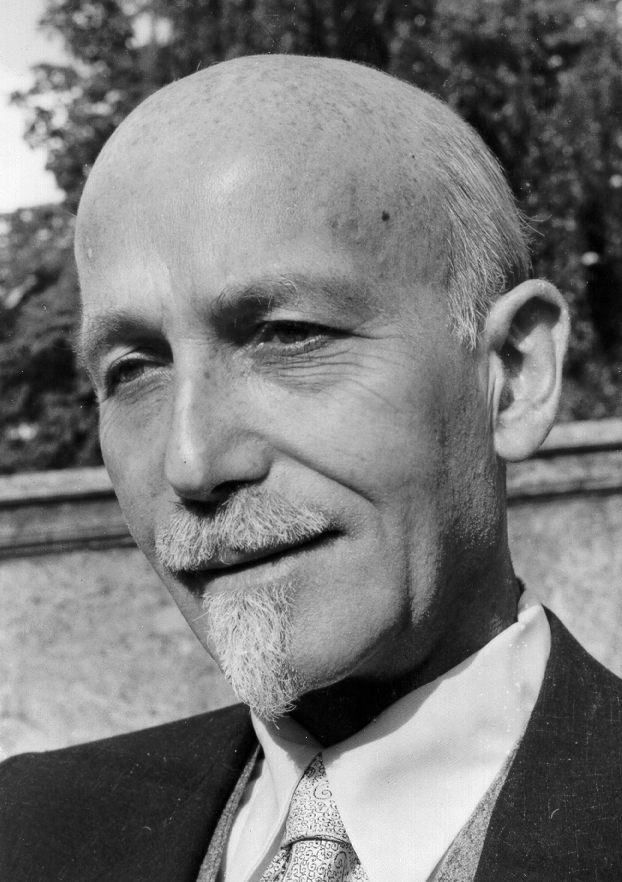

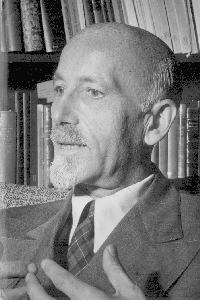

Perspectives is a representative survey of more than seven thousand pages of notes Paul Brunton (1898–1981) withheld for posthumous publication. It introduces a much larger work that he spoke of as his “Summing Up.”

To reap the greatest spiritual harvest from these “seed thoughts,” particularly those written after April of 1963, we should try to appreciate a condition of mind heart that is rare in any century. Plotinus gives one of the best reports of this attainment when he writes:

The Intellectual-Principle is a self-intent activity, but Soul has the double phase, one inner, intent upon Intellectual-Principle, the other outside it and facing to the external; by the one it holds the likeness to its source; by the other, even in its unlikeness, it still comes to likeness in this sphere, too, by virtue of action and production; in its action it still contemplates, and its production produces forms—detached intellections, so to speak—with the result that all its creations are representations of the divine Intellection and of the divine Intellect, moulded upon the archetype, of which all are emanations and images, the nearer the more true, the very latest preserving some faint likeness of the source. —V.3.7, MacKenna translation

It would be an error to think even of a sage as operating with the omniscience of the Divine Mind (Intellectual-Principle). But we can think of a sage—insofar as the sage does at times speak thoughts of that Divine Mind with which he or she has become inwardly attuned—as producing “detached intellections,” spiritual intuitions, and translating them into contemporary language. The World-Mind (Intellectual-Principle, God) uses such purified, ennobled, and spiritually mature individuals as vehicles through which it can fashion representations of itself in our world. The aphorisms and philosophic maxims of such sages give us a dim reflection, at least, of what is going on in the depths of the Mystery—depths of which we are aware, but which we are unable to penetrate without the help of superior wisdom.

Whenever such writings are produced, the task of “organizing” them proves insurmountable. Thousands of truly great and inspired minds have discovered through reading the Hindu Upanishads, for example, that it is impossible to reduce all the spiritual intuitions “captured” in them to any kind of systematic whole. Anyone who has sincerely tried has given up the task as hopeless. Some have found through their effort to do so, however, that the mind that coldly systematizes is on a lower plane than that which discovers in moments of awe. The kind of logical and coherent order that we find so important for the preservation of our sanity in the world of the senses is out of place in the realm of such discovery. It is transcended, though certainly not contradicted, by the unimaginably grand Divine Order of which our own best thoughts are but meager representations. To demand that the greater conform to the laws of the lesser is to deprive ourselves of our own best.

The stilled, introverted, and receptive mind of the sage perfectly mirrors the powers of the Divine Mind that unfold temporally as all that is real or true in our world. When appropriate conditions exist, the sage may be used to announce outwardly what is being thought in an indivisible way in the undivided larger Mind—with which the sage is inwardly at one and outwardly in harmony. The Divine Mind's ideation remains indivisible and whole, but its representation in our world (through the sage who writes or speaks with its inspiration) conforms to the laws of temporality and contemporary language. Though what the sage gives us through speech or writing not to be equated with the undifferentiated Intelligence of the living universal Consciousness, it is in truth an accurate reflection of That in terms more accessible to our spiritually younger minds. A functioning Wisdom that cannot be fathomed becomes dimly available to us; something of its master plan becomes available to guide our daily aspirations.

Such sages, as we read in chapter twenty-five, remain—or, more accurately, become—fully human. They verify in their being and life the attainability for ourselves of such ennoblement and self-completion. In one sense the simplest, in another the most complex of human beings, the fully developed sage fashions a legacy that is much more than an intellectual one—though it of course includes that as well. It is not a hard-and-fast, tightly formulated, systematic doctrine all on one level. Rather it is a multi-faceted and open-ended way of seeing and being, a Vision unfolding and completing itself within us as our own best selves becoming actual.

In fulfilling their spiritual birthright, such pioneers of humanity affirm the eventual fulfillment of a similar seed within each one of us. We can feel all that is good and noble within us being nourished by the inner Knower affirming itself in their written and spoken words.

A few remarks are also required about the form of these writings and the structure of their organization by category. Throughout the thirty years during which he refrained from publishing new material, P.B. deepened and broadened his research into spiritual matters and wrote daily. His method of writing involved a minimum of three well-defined stages for a given piece of material.

First he would jot down brief notes while an intuition was fresh and vital. He used whatever was at hand, anything ranging from a pocket notebook to the back of an envelope to a crumpled gum wrapper or matchbook. These handwritten notes were later organized by topic, typed, and filed as “Rough Ideas.” He regularly reviewed the material in this stage and revised many of the notes there into more literary form. The revised versions were then typed afresh and filed by topic in notebooks entitled “Middle Ideas.” A second review and literary revision followed, after which the “final” material was typed and then put into notebooks titled simply “Ideas.” At any given time, new material for each stage could be found in his workroom.

P.B.'s preference for this form or writing is best expressed in one of his own entries, written probably in 1980:

To write a book that will sustain a single theme through three hundred pages is an admirable intellectual achievement, but it is not really my way; I have done with it since long ago. A man must express himself in his own way, the way which follows the nature he is born with. I prefer to write down a single idea without any reference to those which went before or which are to follow later, and to write it down in a concentrated way. The only book I could prepare now would be a book of maxims of suggestive ideas. I have not the patience to go on and on, telling someone in a hundred pages what I could put into a single page.

By the time the two present editors were invited to the project, more than seven thousand single-spaced pages of such “detached intellections” had been produced, along with approximately three thousand pages of related research material. During his last two years, P.B. conceived his final system of classification and began training a few students to bring the existing notes into conformity with his new categories. After his death July 27, 1981, we worked with numerous volunteers for seven years to complete the reclassification to the best of our ability in keeping with his guidelines. Readers should be aware that while the writings themselves are those of a sage, the organization is largely the work of students. Often a passage could fit more than one category, and we chose what seemed to us the most appropriate. The placement in some cases is admittedly arbitrary and should be recognized as such.

[In the printed edition of The Notebooks, P.B.'s final schema appears as the table of contents for Perspectives and at the end of each volume. For the CD ROM edition, it appears at the end of this introduction.]

The arbitrariness that applies to placement applies to some extent also to the contents of this survey. A work for general publication must try to anticipate the level of its audience, and there is little doubt that other people would have selected different writings from the voluminous array of possible choices. The original notebooks consist of “paras,” as P.B. called them, addressing a variety of types of people and many different levels of development within similar types. In the same spirit, we tried to be representative of the actual material: advice is offered for many different types and many different levels. Where apparent contradictions surface, consider first that the advice may be for someone at a different level than yourself. Take what is relevant and valuable for you. Others may benefit from what does not appeal to you or apply to your present level.

Punctuation and capitalization are almost entirely as in P.B.'s original notebooks. Whereas standard stylebooks dictate many required “improvements,” we left the vast majority of the paras untouched. In general, we opted for authenticity rather than to impose our own stylistic preferences. We made minor modifications only in those relatively few cases where—particularly in the “rough” and “middle” stages—we agree that P.B. would approve them as clarifying his meaning or expressing it more smoothly. This is a process each of us worked on with him frequently during his last two years. Wherever we do not agree, problematic paras stand as written for readers to debate what P.B. would have done with them.

We have made three useful concessions to the “hobgoblin” of consistency. We maintained P.B.’s British spelling and made it conform to the Oxford English Dictionary, with the following exception: When O.E.D. lists two correct spellings of which only one appears in Webster's Third International, we chose the entry common to both. Also, we applied the University of Chicago serial comma rule to those series in which commas already appeared in the notebooks. Our policy with respect to gender sensitive literary style is explained in the General Introduction to the CD ROM. Finally, we established consistent hyphenation in compound words.

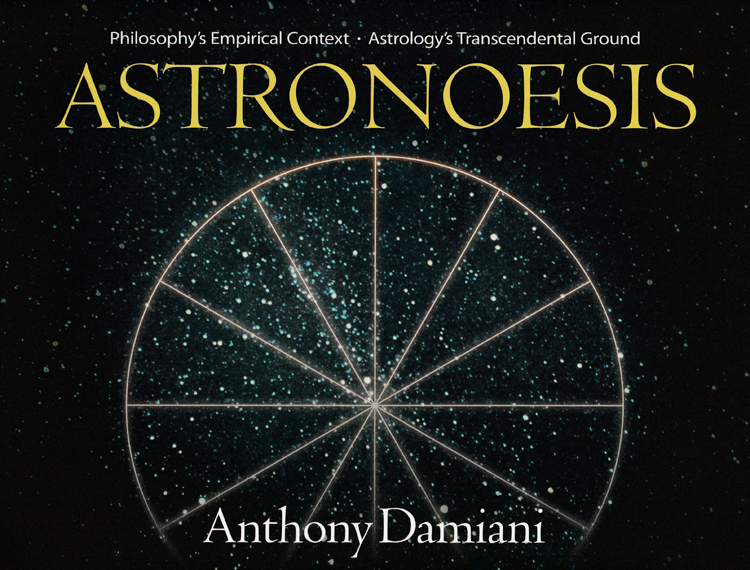

We hope that P.B.'s readers will forgive our personal shortcomings that find expression in this and subsequent sections of The Notebooks, and that they will sympathize with our sincerity in doing the best and most thorough job we could do. We are grateful to P.B. for his grace and guidance, and to Anthony Damiani for his essential and inspiring direction in the early years of the project and on this selection in particular. We are also deeply grateful for the extensive clerical, editorial, financial, and moral support given to this project by many friends at Wisdom's Goldenrod Center for Philosophic Studies and from P.B. readers throughout the world.

Paul Cash

Timothy J. Smith

© Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation

THIS BOOK IS MADE DEDICATE

to that Sage of the Orient at whose behest these pages were written: to one incredibly wise and ceaselessly beneficent. And, further, I have wrapped this book in the bright orange-chrome coloured cloth even as you have wrapped your body in cloth of the same colour—the Sannyasi's colour—the mark of one who has renounced the world as you have. And if the dealings of the cards of destiny bid me wear cloth of another hue, command me to mix and mingle with the world and help carry on its work, be assured that somewhere in the deep places of my heart, I have gathered all my desired into a little heap and offered them all unto the Nameless Higher Power. —P.B.

Prefatory:

The way to use a philosophic book is not to expect to understand all of it at the first trial, and consequently not to get disheartened when failure to understand is frequent. Using this cautionary approach, carefully note each phrase or paragraph that brings an intuitive response in your heart's deep feeling (not to be confused with an intellectual acquiescence in the head's logical working). As soon as, and every time, this happens, stop your reading, put the book momentarily aside, and surrender yourself to the activating words alone. Let them work upon you in their own way. You are merely to be quiet and be receptive. For it is out of such a response that you may eventually find that a door opens to your inner being and a light shines where there was none before. When you pass through that doorway and step into that light, the rest of the book will be easy to understand. —P.B.

If you feel that the principles touched on in these pages are true, then remember that the greatest homage you can pay to Truth is to use it. Spiritual peace is given as a prize to those who wisely aspire, and who will work untiringly for the realization of their aspiration. —P.B.

From Chapter 1: THE QUEST

1

The Quest of the Overself is none other than the final stage of mankind's long pursuit of happiness.

2

When a man feels imperatively the need of respecting himself, he has heard a faint whisper from his Overself. Henceforth he begins to seek out ways and means for earning that respect. This begins his Quest.

3

The central point of this quest is the inner opening of the ego's heart to the Overself.

4

It is not for those who feel the want of a social meeting every Sunday morning, where they can display their good clothes and listen to good words. It is for those who feel the want of something great in life to which they can give themselves, who cannot rest satisfied with the business of earning their bread and butter alone or spending their time in pleasures. What cause, what mission can be greater than fulfilling the higher purpose of life on earth?

5

We are here on earth in pursuit of a sacred mission. We have to find what theologians call the soul, what philosophers call the Overself. It is something which is at one and the same time both near at hand and yet far off. For it is the secret source of our life-current, our selfhood, and our consciousness. But because our life-energy is continuously streaming outwards through the senses, because our selfhood is continuously identified with the body, and because our consciousness never contemplates itself, the Overself necessarily eludes us utterly.

6

There are four goals which philosophy sets before the mind of man: (1) to know itself; (2) to know its Overself; (3) to know the Universe; (4) to know its relation to the universe. The search for these goals constitutes the quest.

7

It is this Ideal that gives a secret importance to every phase of our life-experience. It is this goal that invests unknown and unnoticed men and women with Olympic grandeur. It is this Thought that redeems, exalts, and glorifies human existence.

8

A humble life dedicated to a great purpose, becomes great.

From Chapter 6: EMOTIONS AND ETHICS

1

We begin and end the study of philosophy by a consideration of the subject of ethics. Without a certain ethical discipline to start with, the mind will distort truth to suit its own fancies. Without a mastery of the whole course of philosophy to its very end, the problem of the significance of good and evil cannot be solved.

2

The pursuit of moral excellence is immeasurably better than the pursuit of mystical sensations. Its gains are more durable, more indispensable, and more valuable.

3

The philosophical discipline seeks to build up a character which no weakness can undermine and from which all negative characteristics have been thrown out.

4

There are five ways in which the human being progressively views his own self and consequently five graduated ethical stages on his quest. First, as an ignorant materialist he lives entirely within his personality and hence for personal benefit regardless of much hurt caused to others in order to secure this benefit. Second, as an enlightened materialist he is wrapped in his own fortunes but does not seek them at the expense of others. Third, as a religionist he perceives the impermanence of the ego and, with a sense of sacrifice, he denies his self-will. Fourth, as a mystic he acknowledges the existence of a higher power, God, but finds it only within himself. Fifth, as a philosopher he recognizes the universality and the oneness of being in others and practises altruism with joy.

5

The moral precepts which it offers for use in living and for guidance in wise action are not offered to all alike, but only to those engaged on the quest. They are not likely to appeal to anyone who is virtuous merely because he fears the punishment of sin rather than because he loves virtue itself. Nor are they likely to appeal to anyone who does not know where his true self-interest lies. There would be nothing wrong in being utterly selfish if only we fully understood the self whose interest we desire to preserve or promote. For then we would not mistake pleasure for happiness nor confuse evil with good. Then we would see that earthly self-restraint in some directions is in reality holy self-affirmation in others, and that the hidden part of self is the best part.

6

We have begun to question Nature and we must abide the consequences. But we need not fear the advancing tide of knowledge. Its effects on morals will be only to discipline human character all the more. For it is not knowledge that makes men immoral, it is the lack of it. False foundations make uncertain supports for morality.

7

This grand section of the quest deals with the right conduct of life. It seeks both the moral re-education of the individual's character for his own benefit and the altruistic transformation of it for society's benefit.

8

If you want to obtain a good objective, you must use a good means as no other will bring the same result.

From Chapter 15: THE ORIENT

1

The present day needs not only a synthesis of Oriental and Occidental ideas, but also a new creative universal outlook that will transcend both. A world civilization will one day come into being through inward propulsion and outward compulsion. And it will be integral; it will engage all sides of human development, not merely one side as hitherto.

2

Those Westerners who try to ape Indians—and not only Indians, but the ancient Indians at that—by adopting their dress, clothes, beliefs, and general way of life are putting themselves in a somewhat ridiculous position, if not a false one. We may give admiration and sympathy to Indian ideas and ideals up to a certain point, but we need not do it by throwing away completely all our Western heritage, which also has its substantial value. We need not let them prevent us from giving an adequate appreciation to the offerings of our own culture.

3

The Western peoples will never be converted wholesale to Hinduism or Buddhism as religions, nor will their intelligentsia take wholesale to Vedanta or Theosophy as philosophies. These forms are too alien and too exotic to affect the general mass. Historically, they have only succeeded in affecting scattered individuals. The West's spiritual revival must and can come only out of its own creative and native mind.

4

He would do well to give respect, veneration, and love to the Oriental Wisdom. For when the structures that we Westerners have put up are gone, its verities will still be there, unchanged and unchangeable.

5

Sir S. Radhakrishnan, Vice President of the Indian Republic and honoured expounder of Indian philosophy, has humbly said that “there is much we have to learn from the peoples of the West and there is also a little which the West may learn from us.” My own travel and observation in both hemispheres lead to a less humble conclusion. What each has to learn from the other is about equal.

6

I have for some years kept myself apart from Indian spiritual movements of every kind and do not wish to get associated with them in any way. Consequently, I shall not resume my contact with any swami or yogi, for I wish to work in utter independence of them. My reasons are based on the illuminations which have come to me, on my understanding that the West must work out its own salvation, and on the narrow minded intolerance of the Indian mentality towards any such creative endeavour on the West's part.

From Chapter 23: ADVANCED CONTEMPLATION

1

He should remember that there are two approaches to the Quest and both have to be used. There is the Long Path of self-improvement, self-purification, and self-effort; and there is the Short Path of forgetting the self entirely and directing his mind towards the Goal, towards the One Real Life, by constant remembrance of it and by practising self-identification with it. If he uses the first approach, he can progress to a certain point. But by bringing in the second approach, the Higher Power is brought in too and comes to his help with Grace.

2

The Short Path advocates who decry the need of the Long Path altogether because, being divine in essence, we have only to realize what we already are, are misled by their own half-truth. What we actually find in the human situation is that we are only potentially divine. The work of drawing out and developing this potential still needs to be done. This takes time, discipline, and training, just as the work of converting a seed into a tree takes time.

3

The limitation of the Long Path is that it is concerned only with thinning down, weakening, and reducing the ego's strength. It is not concerned with totally deflating the ego. Since this can be done only by studying the ego's nature metaphysically, seeing its falsity, and recognizing its illusoriness, which is not even done by the Short Path, then all the endeavours of the Short Path to practise self-identification with the Overself are merely using imagination and suggestion to create a new mental state that, while imitating the Overself's state, does not actually transcend the ego-mind but exists within it still. So a third phase becomes necessary, the phase of getting rid of the ego altogether; this can be done only by the final dissolving operation of Grace, which the man has to request and to which he has to give his consent. To summarize the entire process, the Long Path leads to the Short Path, and the Short Path leads to the Grace of an unbroken egoless consciousness.

4

Those who depend solely on the Short Path without being totally ready for it take too much for granted and make too much of a demand. This is arrogance. Instead of opening the door, such an attitude can only close it tighter. Those who depend solely on the Long Path take too much on their shoulders and burden themselves with a purificatory work which not even an entire lifetime can bring to an end. This is futility. It causes them to evolve at a slower rate. The wiser and philosophic procedure is to couple together the work on both paths in a regularly alternating rhythm, so that during the course of a year two totally different kinds of results begin to appear in the character and the behaviour, in the consciousness and the understanding. After all, we see this cycle everywhere in Nature, and in every other activity she compels us to conform to it. We see the alternation of sleep with waking, work with rest, and day with night.

5

The Long Path is taught to beginners and others in the earlier and middle stages of the quest. This is because they are ready for the idea of self-improvement and not for the higher one of the unreality of the self. So the latter is taught on the Short Path, where attention is turned away from the little self and from the idea of perfecting it, to the essence, the real being.

36

The practice of extending love towards all living creatures brings on ecstatic states of cosmic joy.

37

These exercises are for those who are not mere beginners in yoga. Such are necessarily few. The different yogas are successive and do not oppose each other. The elementary systems prepare the student to practise the more advanced ones. Anybody who tries to jump all at once to the philosophic yoga without some preliminary ripening may succeed if he has the innate capacity to do so but is more likely to fail altogether through his very unfamiliarity with the subject. Hence these ultramystic exercises yield their full fruit only if the student has come prepared either with previous meditational experience or with mentalist, metaphysical understanding—or better still with both. Anyone who starts them, because of their apparent simplicity, without such preparation must not blame the exercises if he fails to obtain results. They are primarily intended for the use of advanced students of metaphysics on the one hand or of advanced practitioners of meditation on the other. This is because the first class will understand correctly the nature of the Mind-in-itself which they should strive to attain thereby, whilst the second class will have had sufficient self-training not to set up artificial barriers to the influx when it begins.

38

Although the writer regards it as unnecessary and inadvisable to disclose in a work of popular instruction those further secrets of a more advanced practice which act as short cuts to attainment for those who are ready to receive them, suffice to say that whoever will take up this path and go through the disciplinary practices here given faithfully and willingly until he is sufficiently advanced to profit by the further initiation of those secrets, may rest assured that at the right time he will be led to someone or else someone will be led to him and the requisite initiation will then be given him. Such is the wonderful working of the universal soul which broods over this earth of ours and over all mankind. No one is too insignificant to escape its notice just as no one is deprived of the illumination which is his due; but everything in nature is graduated, so the hands of the planetary clock must go round and the right hour be struck ere the aspirant makes the personal contact which in nine cases out of ten is the preliminary to entry into a higher realization of these spiritual truths.

39

Being based on the mentalist principles of the hidden teaching, they were traditionally regarded as being beyond yoga. Hence these exercises have been handed down by word of mouth only for thousands of years and, in their totality, have not, so far as our knowledge extends, been published before, whether in any ancient Oriental language like Sanskrit or in any modern language like English. They are not yoga exercises in the technical sense of that term and they cannot be practised by anyone who has never before practised yoga.

46

When we comprehend that the pure essence of mind is reality, then we can also comprehend the rationale of the higher yoga which would settle attention in pure thought itself rather than in finite thoughts. When this is done the mind becomes vacant, still, and utterly undisturbed. This grand calm of nonduality comes to the philosophic yogi alone and is not to be confused with the lower-mystical experience of emotional ecstasy, clairvoyant vision, and inner voice. For in the latter the ego is present as its enjoyer, whereas in the former it is absent because the philosophic discipline has led to its denial. The lower type of mystic must make a special effort to gain his ecstatic experience, but the higher type finds it arises spontaneously without personal effort at all. The first is in the realm of duality, whilst the second has realized nonduality.

47

There is, in this third stage, a condition that never fails to arouse the greatest wonder when initiation into it begins. In certain ways it corresponds to, and mentally parallels, the condition of the embryo in a mother's womb. Therefore, it is called by mystics who have experienced it “the second birth.” The mind is drawn so deeply into itself and becomes so engrossed in itself that the outer world vanishes utterly. The sensation of being enclosed all round by a greater presence, at once protective and benevolent, is strong. There is a feeling of being completely at rest in this soothing presence. The breathing becomes very quiet and hardly perceptible. One is aware also that nourishment is being mysteriously and rhythmically drawn from the universal Life-force. Of course, there is no intellectual activity, no thinking, and no need of it. Instead, there is a k-n-o-w-i-n-g. There are no desires, no wishes, no wants. A happy peacefulness, almost verging on bliss, as human love might be without its passions and pettinesses, holds one in magical thrall. In its freedom from mental working and perturbation, from passional movement and emotional agitation, the condition bears something of infantile innocence. Hence Jesus' saying: “Except ye become as little children ye shall in no wise enter the Kingdom of Heaven.” But essentially it is a return to a spiritual womb, to being born again into a new world of being where at the beginning he is personally as helpless, as weak, and as dependent as the physical embryo itself.

In his own words:

“Writing, which is an exercise of the intellect to some, is an act of worship to me. I rise from my desk in the same mood as that in which I leave an hour of prayer in an old cathedral, or of meditation in a little wood . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 143

“P.B. as a private person does not count. There are hundreds of millions of such persons anyway. What is one man and his quest? P.B.’s personal experiences and views are not of any particular importance or special consequence. What happens to the individual man named P.B. is a matter of no account to anyone except himself. But what happens to the hundreds of thousands of spiritual seekers today who are following the same path that he pioneered is a serious matter and calls for prolonged consideration. Surely the hundreds of thousands of Western seekers who stand behind him and whom indeed, in one sense, he represents, do count. P.B. as a symbol of the scattered group of Western truth-seekers who, by following his writings so increasingly and so eagerly, virtually follow him also, does count. He personifies their aspirations, their repulsion from materialism and attraction toward mysticism, their interest in Oriental wisdom and their shepherdless state. As a symbol of this Western movement of thought, he is vastly greater than himself. In his mind and person the historic need for a new grasp of the contemporary spiritual problem found a plain-speaking voice . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 145

Learn more about Paul Brunton through articles at the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation web site

Ebook

Electronic versions of this book are available from all major (Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, etc.) and most smaller ebook vendors. Please don't try to order ebooks directly from us, as we are not yet able to deliver anything to you in a preferred electronic format.

Hardcover

We are currently out of stock of this volume in hardcover.

To see all our Paul Brunton titles, scroll down to The Complete Paul Brunton Opus below.

To see and/or order individual volumes in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, hover your mouse over the specific cover in the Notebooks section of Complete Paul Brunton Opus below, then click on Details in the box that appears within it.

Click here to see or order the complete set of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

Paul Brunton helps us hear the melody behind the medley of today's "spiritual marketplace." His late writings raise the bar for what we can expect of spiritual teachings and teachers, and what we can do for ourselves. Born in London in 1898, he soon became a leading pioneer of much of what we now take for granted. He traveled widely throughout the world (long before it was fashionable) to meet living masters of various traditions with whom he then lived and studied. His eleven early books from 1934–1952 shared much of what he learned, and helped set the stage for dramatic east-west exchanges of the late 20th century. Paul Brunton left more than 10,000 pages of enormously helpful new work in notebooks he reserved for posthumous publication, much of which is now available as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. See "The Complete Paul Brunton Opus" in blue below to see his many works available on this site. You can also search on Paul Brunton in the search bar to browse the selections, or click on a link below for specific connections.

Click here for an article about Paul Brunton.

Click here for The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

To access small theme-based books compiled from Paul Brunton's writings, scroll down to Derived from the Notebooks below.

To access Paul Brunton's early writings, published from 1934–1952, scroll down to Paul Brunton's Early Works below.

To access commentaries on Paul Brunton and his work by his leading student, Anthony Damiani, as well as other writings about Paul Brunton and/or his work, scroll down to Commentaries and Reflections on Paul Brunton and His Work below.

Book Details

This is a great place to start reading Paul Brunton's posthumously published Notebooks — an uplifting, enlightening, and representative survey of virtually every aspect of spiritual awakening and stage of practice. Each of its 28 chapters samples one of the 28 “categories” into which Paul Brunton filed his writings. Topics included are:

- meditation

- the body

- emotions and ethics

- the intellect

- the ego

- world crisis

- the arts in culture

- psychic experiences

- philosophy

- the Overself

- cosmology

- the Absolute

- and much more (see table of contents)

Subsequent volumes in the series focus in detail on individual categories in the 1–28 outline structure.

See tabs below for a full table of contents, the editors’ introduction, some samples from the text, and selected highlights from this noteworthy volume’s many favorable reviews.

1. THE QUEST

Its choice—Independent path—Organized groups—Self-development—Student/teacher

2. PRACTICES FOR THE QUEST

Ant's long path—Work on oneself

3. RELAX AND RETREAT

Intermittent pauses—Tension and pressures—Relax body, breath, and mind—Retreat centres—Solitude—Nature

appreciation—Sunset contemplation

4. ELEMENTARY MEDITATION

Place and conditions—Wandering thoughts—Practice concentrated attention—Meditative thinking—Visualized images

—Mantrams—Symbols—Affirmations and suggestions

5. THE BODY

Hygiene and cleansings—Food—Exercises and postures—Breathings—Sex: importance, influence, effects

6. EMOTIONS AND ETHICS

Uplift character—Re-educate feelings—Discipline emotions—Purify passions—Refinement and courtesy—Avoid

fanaticism

7. THE INTELLECT

Nature—Services—Development—Semantic training—Science—Metaphysics—Abstract thinking

8. THE EGO

What am I—The I-thought—The psyche

9. FROM BIRTH TO REBIRTH

Experience of dying—After death—Rebirth—Past tendencies --Destiny—Freedom—Astrology

10. HEALING OF THE SELF

Karma, connection with health—Life-force in health and sickness—Drugs and drink in mind-body relationship—Etheric

and astral bodies in health and sickness—Mental disorders—Psychology and psychoanalysis

11. THE NEGATIVES

Nature—Roots in ego—Presence in the world—In thoughts, feelings, and violent passions—Their visible and invisible

harm

12. REFLECTIONS

13. HUMAN EXPERIENCE

Situation—Events—Lessons—World Crisis—Reflections in old age—Reflections on youth

14. THE ARTS IN CULTURE

Appreciation—Creativity—Genius—Art experience and mysticism—Reflections on pictures, sculpture, literature,

poetry, music

15. THE ORIENT

Meetings with the Occident—Oriental people, places, practices—Sayings of philosophers—Schools of philosophy

16. THE SENSITIVES

Psychic and auric experiences—Intuitions—Sects and cults

17. THE RELIGIOUS URGE

Origin—Recognition—Manifestations—Traditional and less known religions—Connection with philosophy

18. THE REVERENTIAL LIFE

Prayer—Devotion—Worship—Humility—Surrender—Grace: real and imagined

19. THE REIGN OF RELATIVITY

Consciousness is relative—Dream, sleep, and wakefulness—Time as past, present, and future—Space

—Twofold standpoint—Void as metaphysical fact

20. WHAT IS PHILOSOPHY?

Definition—Completeness—Balance—Fulfillment in man

21. MENTALISM

Mind and the five senses—World as mental experience—Mentalism is key to the spiritual world

22. INSPIRATION AND THE OVERSELF

Intuition the beginning—Inspiration the completion—Its presence—Glimpses

23. ADVANCED CONTEMPLATION

Ant's long path—Bird's direct path—Exercises for practice—Contemplative stillness—”Why Buddha smiled”—Heavenly

Way exercise—Serpent's Path exercise—Void as contemplative experience

24. THE PEACE WITHIN YOU

Be calm—Practise detachment—Seek the deeper Stillness

25. WORLD-MIND IN INDIVIDUAL MIND

Their meeting and interchange—Enlightenment which stays—Saints and sages

26. THE WORLD-IDEA

Divine order of the universe—Change as universal activity—Polarities, complementaries, and dualities of

the universe—True idea of man

27. WORLD MIND

God as the Supreme Individual—God as Mind-in-activity—As Solar Logos

28. THE ALONE

Mind-in-Itself—The Unique Mind—As Absolute

“. . . a veritable treasure-trove of philosophic-spiritual wisdom.” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

“. . . sensible and compelling. His work can stand beside that of such East-West bridges as Merton, Huxley, Suzuki, Watts, and Radhakrishnan. It should appeal to anyone concerned personally and academically with issues of spirituality.” —Choice

“Vigorous, clear-minded and independent . . . a synthesis of Eastern mysticism and Western rationality. . . A rich volume.” —Library Journal

“. . . a great gift to us Westerners who are seeking the spiritual.” —Charles T. Tart

“A person of rare intelligence. . . thoroughly alive, and whole in the most significant, 'holy' sense of the word.” —Yoga Journal

For more reviews of the Notebooks series, click here

Editors' Introduction

Perspectives is a representative survey of more than seven thousand pages of notes Paul Brunton (1898–1981) withheld for posthumous publication. It introduces a much larger work that he spoke of as his “Summing Up.”

To reap the greatest spiritual harvest from these “seed thoughts,” particularly those written after April of 1963, we should try to appreciate a condition of mind heart that is rare in any century. Plotinus gives one of the best reports of this attainment when he writes:

The Intellectual-Principle is a self-intent activity, but Soul has the double phase, one inner, intent upon Intellectual-Principle, the other outside it and facing to the external; by the one it holds the likeness to its source; by the other, even in its unlikeness, it still comes to likeness in this sphere, too, by virtue of action and production; in its action it still contemplates, and its production produces forms—detached intellections, so to speak—with the result that all its creations are representations of the divine Intellection and of the divine Intellect, moulded upon the archetype, of which all are emanations and images, the nearer the more true, the very latest preserving some faint likeness of the source. —V.3.7, MacKenna translation

It would be an error to think even of a sage as operating with the omniscience of the Divine Mind (Intellectual-Principle). But we can think of a sage—insofar as the sage does at times speak thoughts of that Divine Mind with which he or she has become inwardly attuned—as producing “detached intellections,” spiritual intuitions, and translating them into contemporary language. The World-Mind (Intellectual-Principle, God) uses such purified, ennobled, and spiritually mature individuals as vehicles through which it can fashion representations of itself in our world. The aphorisms and philosophic maxims of such sages give us a dim reflection, at least, of what is going on in the depths of the Mystery—depths of which we are aware, but which we are unable to penetrate without the help of superior wisdom.

Whenever such writings are produced, the task of “organizing” them proves insurmountable. Thousands of truly great and inspired minds have discovered through reading the Hindu Upanishads, for example, that it is impossible to reduce all the spiritual intuitions “captured” in them to any kind of systematic whole. Anyone who has sincerely tried has given up the task as hopeless. Some have found through their effort to do so, however, that the mind that coldly systematizes is on a lower plane than that which discovers in moments of awe. The kind of logical and coherent order that we find so important for the preservation of our sanity in the world of the senses is out of place in the realm of such discovery. It is transcended, though certainly not contradicted, by the unimaginably grand Divine Order of which our own best thoughts are but meager representations. To demand that the greater conform to the laws of the lesser is to deprive ourselves of our own best.

The stilled, introverted, and receptive mind of the sage perfectly mirrors the powers of the Divine Mind that unfold temporally as all that is real or true in our world. When appropriate conditions exist, the sage may be used to announce outwardly what is being thought in an indivisible way in the undivided larger Mind—with which the sage is inwardly at one and outwardly in harmony. The Divine Mind's ideation remains indivisible and whole, but its representation in our world (through the sage who writes or speaks with its inspiration) conforms to the laws of temporality and contemporary language. Though what the sage gives us through speech or writing not to be equated with the undifferentiated Intelligence of the living universal Consciousness, it is in truth an accurate reflection of That in terms more accessible to our spiritually younger minds. A functioning Wisdom that cannot be fathomed becomes dimly available to us; something of its master plan becomes available to guide our daily aspirations.

Such sages, as we read in chapter twenty-five, remain—or, more accurately, become—fully human. They verify in their being and life the attainability for ourselves of such ennoblement and self-completion. In one sense the simplest, in another the most complex of human beings, the fully developed sage fashions a legacy that is much more than an intellectual one—though it of course includes that as well. It is not a hard-and-fast, tightly formulated, systematic doctrine all on one level. Rather it is a multi-faceted and open-ended way of seeing and being, a Vision unfolding and completing itself within us as our own best selves becoming actual.

In fulfilling their spiritual birthright, such pioneers of humanity affirm the eventual fulfillment of a similar seed within each one of us. We can feel all that is good and noble within us being nourished by the inner Knower affirming itself in their written and spoken words.

A few remarks are also required about the form of these writings and the structure of their organization by category. Throughout the thirty years during which he refrained from publishing new material, P.B. deepened and broadened his research into spiritual matters and wrote daily. His method of writing involved a minimum of three well-defined stages for a given piece of material.

First he would jot down brief notes while an intuition was fresh and vital. He used whatever was at hand, anything ranging from a pocket notebook to the back of an envelope to a crumpled gum wrapper or matchbook. These handwritten notes were later organized by topic, typed, and filed as “Rough Ideas.” He regularly reviewed the material in this stage and revised many of the notes there into more literary form. The revised versions were then typed afresh and filed by topic in notebooks entitled “Middle Ideas.” A second review and literary revision followed, after which the “final” material was typed and then put into notebooks titled simply “Ideas.” At any given time, new material for each stage could be found in his workroom.

P.B.'s preference for this form or writing is best expressed in one of his own entries, written probably in 1980:

To write a book that will sustain a single theme through three hundred pages is an admirable intellectual achievement, but it is not really my way; I have done with it since long ago. A man must express himself in his own way, the way which follows the nature he is born with. I prefer to write down a single idea without any reference to those which went before or which are to follow later, and to write it down in a concentrated way. The only book I could prepare now would be a book of maxims of suggestive ideas. I have not the patience to go on and on, telling someone in a hundred pages what I could put into a single page.

By the time the two present editors were invited to the project, more than seven thousand single-spaced pages of such “detached intellections” had been produced, along with approximately three thousand pages of related research material. During his last two years, P.B. conceived his final system of classification and began training a few students to bring the existing notes into conformity with his new categories. After his death July 27, 1981, we worked with numerous volunteers for seven years to complete the reclassification to the best of our ability in keeping with his guidelines. Readers should be aware that while the writings themselves are those of a sage, the organization is largely the work of students. Often a passage could fit more than one category, and we chose what seemed to us the most appropriate. The placement in some cases is admittedly arbitrary and should be recognized as such.

[In the printed edition of The Notebooks, P.B.'s final schema appears as the table of contents for Perspectives and at the end of each volume. For the CD ROM edition, it appears at the end of this introduction.]

The arbitrariness that applies to placement applies to some extent also to the contents of this survey. A work for general publication must try to anticipate the level of its audience, and there is little doubt that other people would have selected different writings from the voluminous array of possible choices. The original notebooks consist of “paras,” as P.B. called them, addressing a variety of types of people and many different levels of development within similar types. In the same spirit, we tried to be representative of the actual material: advice is offered for many different types and many different levels. Where apparent contradictions surface, consider first that the advice may be for someone at a different level than yourself. Take what is relevant and valuable for you. Others may benefit from what does not appeal to you or apply to your present level.

Punctuation and capitalization are almost entirely as in P.B.'s original notebooks. Whereas standard stylebooks dictate many required “improvements,” we left the vast majority of the paras untouched. In general, we opted for authenticity rather than to impose our own stylistic preferences. We made minor modifications only in those relatively few cases where—particularly in the “rough” and “middle” stages—we agree that P.B. would approve them as clarifying his meaning or expressing it more smoothly. This is a process each of us worked on with him frequently during his last two years. Wherever we do not agree, problematic paras stand as written for readers to debate what P.B. would have done with them.

We have made three useful concessions to the “hobgoblin” of consistency. We maintained P.B.’s British spelling and made it conform to the Oxford English Dictionary, with the following exception: When O.E.D. lists two correct spellings of which only one appears in Webster's Third International, we chose the entry common to both. Also, we applied the University of Chicago serial comma rule to those series in which commas already appeared in the notebooks. Our policy with respect to gender sensitive literary style is explained in the General Introduction to the CD ROM. Finally, we established consistent hyphenation in compound words.

We hope that P.B.'s readers will forgive our personal shortcomings that find expression in this and subsequent sections of The Notebooks, and that they will sympathize with our sincerity in doing the best and most thorough job we could do. We are grateful to P.B. for his grace and guidance, and to Anthony Damiani for his essential and inspiring direction in the early years of the project and on this selection in particular. We are also deeply grateful for the extensive clerical, editorial, financial, and moral support given to this project by many friends at Wisdom's Goldenrod Center for Philosophic Studies and from P.B. readers throughout the world.

Paul Cash

Timothy J. Smith

© Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation

THIS BOOK IS MADE DEDICATE

to that Sage of the Orient at whose behest these pages were written: to one incredibly wise and ceaselessly beneficent. And, further, I have wrapped this book in the bright orange-chrome coloured cloth even as you have wrapped your body in cloth of the same colour—the Sannyasi's colour—the mark of one who has renounced the world as you have. And if the dealings of the cards of destiny bid me wear cloth of another hue, command me to mix and mingle with the world and help carry on its work, be assured that somewhere in the deep places of my heart, I have gathered all my desired into a little heap and offered them all unto the Nameless Higher Power. —P.B.

Prefatory:

The way to use a philosophic book is not to expect to understand all of it at the first trial, and consequently not to get disheartened when failure to understand is frequent. Using this cautionary approach, carefully note each phrase or paragraph that brings an intuitive response in your heart's deep feeling (not to be confused with an intellectual acquiescence in the head's logical working). As soon as, and every time, this happens, stop your reading, put the book momentarily aside, and surrender yourself to the activating words alone. Let them work upon you in their own way. You are merely to be quiet and be receptive. For it is out of such a response that you may eventually find that a door opens to your inner being and a light shines where there was none before. When you pass through that doorway and step into that light, the rest of the book will be easy to understand. —P.B.

If you feel that the principles touched on in these pages are true, then remember that the greatest homage you can pay to Truth is to use it. Spiritual peace is given as a prize to those who wisely aspire, and who will work untiringly for the realization of their aspiration. —P.B.

From Chapter 1: THE QUEST

1

The Quest of the Overself is none other than the final stage of mankind's long pursuit of happiness.

2

When a man feels imperatively the need of respecting himself, he has heard a faint whisper from his Overself. Henceforth he begins to seek out ways and means for earning that respect. This begins his Quest.

3

The central point of this quest is the inner opening of the ego's heart to the Overself.

4

It is not for those who feel the want of a social meeting every Sunday morning, where they can display their good clothes and listen to good words. It is for those who feel the want of something great in life to which they can give themselves, who cannot rest satisfied with the business of earning their bread and butter alone or spending their time in pleasures. What cause, what mission can be greater than fulfilling the higher purpose of life on earth?

5

We are here on earth in pursuit of a sacred mission. We have to find what theologians call the soul, what philosophers call the Overself. It is something which is at one and the same time both near at hand and yet far off. For it is the secret source of our life-current, our selfhood, and our consciousness. But because our life-energy is continuously streaming outwards through the senses, because our selfhood is continuously identified with the body, and because our consciousness never contemplates itself, the Overself necessarily eludes us utterly.

6

There are four goals which philosophy sets before the mind of man: (1) to know itself; (2) to know its Overself; (3) to know the Universe; (4) to know its relation to the universe. The search for these goals constitutes the quest.

7

It is this Ideal that gives a secret importance to every phase of our life-experience. It is this goal that invests unknown and unnoticed men and women with Olympic grandeur. It is this Thought that redeems, exalts, and glorifies human existence.

8

A humble life dedicated to a great purpose, becomes great.

From Chapter 6: EMOTIONS AND ETHICS

1

We begin and end the study of philosophy by a consideration of the subject of ethics. Without a certain ethical discipline to start with, the mind will distort truth to suit its own fancies. Without a mastery of the whole course of philosophy to its very end, the problem of the significance of good and evil cannot be solved.

2

The pursuit of moral excellence is immeasurably better than the pursuit of mystical sensations. Its gains are more durable, more indispensable, and more valuable.

3

The philosophical discipline seeks to build up a character which no weakness can undermine and from which all negative characteristics have been thrown out.

4

There are five ways in which the human being progressively views his own self and consequently five graduated ethical stages on his quest. First, as an ignorant materialist he lives entirely within his personality and hence for personal benefit regardless of much hurt caused to others in order to secure this benefit. Second, as an enlightened materialist he is wrapped in his own fortunes but does not seek them at the expense of others. Third, as a religionist he perceives the impermanence of the ego and, with a sense of sacrifice, he denies his self-will. Fourth, as a mystic he acknowledges the existence of a higher power, God, but finds it only within himself. Fifth, as a philosopher he recognizes the universality and the oneness of being in others and practises altruism with joy.

5

The moral precepts which it offers for use in living and for guidance in wise action are not offered to all alike, but only to those engaged on the quest. They are not likely to appeal to anyone who is virtuous merely because he fears the punishment of sin rather than because he loves virtue itself. Nor are they likely to appeal to anyone who does not know where his true self-interest lies. There would be nothing wrong in being utterly selfish if only we fully understood the self whose interest we desire to preserve or promote. For then we would not mistake pleasure for happiness nor confuse evil with good. Then we would see that earthly self-restraint in some directions is in reality holy self-affirmation in others, and that the hidden part of self is the best part.

6

We have begun to question Nature and we must abide the consequences. But we need not fear the advancing tide of knowledge. Its effects on morals will be only to discipline human character all the more. For it is not knowledge that makes men immoral, it is the lack of it. False foundations make uncertain supports for morality.

7

This grand section of the quest deals with the right conduct of life. It seeks both the moral re-education of the individual's character for his own benefit and the altruistic transformation of it for society's benefit.

8

If you want to obtain a good objective, you must use a good means as no other will bring the same result.

From Chapter 15: THE ORIENT

1

The present day needs not only a synthesis of Oriental and Occidental ideas, but also a new creative universal outlook that will transcend both. A world civilization will one day come into being through inward propulsion and outward compulsion. And it will be integral; it will engage all sides of human development, not merely one side as hitherto.

2

Those Westerners who try to ape Indians—and not only Indians, but the ancient Indians at that—by adopting their dress, clothes, beliefs, and general way of life are putting themselves in a somewhat ridiculous position, if not a false one. We may give admiration and sympathy to Indian ideas and ideals up to a certain point, but we need not do it by throwing away completely all our Western heritage, which also has its substantial value. We need not let them prevent us from giving an adequate appreciation to the offerings of our own culture.

3

The Western peoples will never be converted wholesale to Hinduism or Buddhism as religions, nor will their intelligentsia take wholesale to Vedanta or Theosophy as philosophies. These forms are too alien and too exotic to affect the general mass. Historically, they have only succeeded in affecting scattered individuals. The West's spiritual revival must and can come only out of its own creative and native mind.

4

He would do well to give respect, veneration, and love to the Oriental Wisdom. For when the structures that we Westerners have put up are gone, its verities will still be there, unchanged and unchangeable.

5

Sir S. Radhakrishnan, Vice President of the Indian Republic and honoured expounder of Indian philosophy, has humbly said that “there is much we have to learn from the peoples of the West and there is also a little which the West may learn from us.” My own travel and observation in both hemispheres lead to a less humble conclusion. What each has to learn from the other is about equal.

6

I have for some years kept myself apart from Indian spiritual movements of every kind and do not wish to get associated with them in any way. Consequently, I shall not resume my contact with any swami or yogi, for I wish to work in utter independence of them. My reasons are based on the illuminations which have come to me, on my understanding that the West must work out its own salvation, and on the narrow minded intolerance of the Indian mentality towards any such creative endeavour on the West's part.

From Chapter 23: ADVANCED CONTEMPLATION

1

He should remember that there are two approaches to the Quest and both have to be used. There is the Long Path of self-improvement, self-purification, and self-effort; and there is the Short Path of forgetting the self entirely and directing his mind towards the Goal, towards the One Real Life, by constant remembrance of it and by practising self-identification with it. If he uses the first approach, he can progress to a certain point. But by bringing in the second approach, the Higher Power is brought in too and comes to his help with Grace.

2

The Short Path advocates who decry the need of the Long Path altogether because, being divine in essence, we have only to realize what we already are, are misled by their own half-truth. What we actually find in the human situation is that we are only potentially divine. The work of drawing out and developing this potential still needs to be done. This takes time, discipline, and training, just as the work of converting a seed into a tree takes time.

3

The limitation of the Long Path is that it is concerned only with thinning down, weakening, and reducing the ego's strength. It is not concerned with totally deflating the ego. Since this can be done only by studying the ego's nature metaphysically, seeing its falsity, and recognizing its illusoriness, which is not even done by the Short Path, then all the endeavours of the Short Path to practise self-identification with the Overself are merely using imagination and suggestion to create a new mental state that, while imitating the Overself's state, does not actually transcend the ego-mind but exists within it still. So a third phase becomes necessary, the phase of getting rid of the ego altogether; this can be done only by the final dissolving operation of Grace, which the man has to request and to which he has to give his consent. To summarize the entire process, the Long Path leads to the Short Path, and the Short Path leads to the Grace of an unbroken egoless consciousness.

4

Those who depend solely on the Short Path without being totally ready for it take too much for granted and make too much of a demand. This is arrogance. Instead of opening the door, such an attitude can only close it tighter. Those who depend solely on the Long Path take too much on their shoulders and burden themselves with a purificatory work which not even an entire lifetime can bring to an end. This is futility. It causes them to evolve at a slower rate. The wiser and philosophic procedure is to couple together the work on both paths in a regularly alternating rhythm, so that during the course of a year two totally different kinds of results begin to appear in the character and the behaviour, in the consciousness and the understanding. After all, we see this cycle everywhere in Nature, and in every other activity she compels us to conform to it. We see the alternation of sleep with waking, work with rest, and day with night.

5

The Long Path is taught to beginners and others in the earlier and middle stages of the quest. This is because they are ready for the idea of self-improvement and not for the higher one of the unreality of the self. So the latter is taught on the Short Path, where attention is turned away from the little self and from the idea of perfecting it, to the essence, the real being.

36

The practice of extending love towards all living creatures brings on ecstatic states of cosmic joy.

37

These exercises are for those who are not mere beginners in yoga. Such are necessarily few. The different yogas are successive and do not oppose each other. The elementary systems prepare the student to practise the more advanced ones. Anybody who tries to jump all at once to the philosophic yoga without some preliminary ripening may succeed if he has the innate capacity to do so but is more likely to fail altogether through his very unfamiliarity with the subject. Hence these ultramystic exercises yield their full fruit only if the student has come prepared either with previous meditational experience or with mentalist, metaphysical understanding—or better still with both. Anyone who starts them, because of their apparent simplicity, without such preparation must not blame the exercises if he fails to obtain results. They are primarily intended for the use of advanced students of metaphysics on the one hand or of advanced practitioners of meditation on the other. This is because the first class will understand correctly the nature of the Mind-in-itself which they should strive to attain thereby, whilst the second class will have had sufficient self-training not to set up artificial barriers to the influx when it begins.

38

Although the writer regards it as unnecessary and inadvisable to disclose in a work of popular instruction those further secrets of a more advanced practice which act as short cuts to attainment for those who are ready to receive them, suffice to say that whoever will take up this path and go through the disciplinary practices here given faithfully and willingly until he is sufficiently advanced to profit by the further initiation of those secrets, may rest assured that at the right time he will be led to someone or else someone will be led to him and the requisite initiation will then be given him. Such is the wonderful working of the universal soul which broods over this earth of ours and over all mankind. No one is too insignificant to escape its notice just as no one is deprived of the illumination which is his due; but everything in nature is graduated, so the hands of the planetary clock must go round and the right hour be struck ere the aspirant makes the personal contact which in nine cases out of ten is the preliminary to entry into a higher realization of these spiritual truths.

39

Being based on the mentalist principles of the hidden teaching, they were traditionally regarded as being beyond yoga. Hence these exercises have been handed down by word of mouth only for thousands of years and, in their totality, have not, so far as our knowledge extends, been published before, whether in any ancient Oriental language like Sanskrit or in any modern language like English. They are not yoga exercises in the technical sense of that term and they cannot be practised by anyone who has never before practised yoga.

46

When we comprehend that the pure essence of mind is reality, then we can also comprehend the rationale of the higher yoga which would settle attention in pure thought itself rather than in finite thoughts. When this is done the mind becomes vacant, still, and utterly undisturbed. This grand calm of nonduality comes to the philosophic yogi alone and is not to be confused with the lower-mystical experience of emotional ecstasy, clairvoyant vision, and inner voice. For in the latter the ego is present as its enjoyer, whereas in the former it is absent because the philosophic discipline has led to its denial. The lower type of mystic must make a special effort to gain his ecstatic experience, but the higher type finds it arises spontaneously without personal effort at all. The first is in the realm of duality, whilst the second has realized nonduality.

47

There is, in this third stage, a condition that never fails to arouse the greatest wonder when initiation into it begins. In certain ways it corresponds to, and mentally parallels, the condition of the embryo in a mother's womb. Therefore, it is called by mystics who have experienced it “the second birth.” The mind is drawn so deeply into itself and becomes so engrossed in itself that the outer world vanishes utterly. The sensation of being enclosed all round by a greater presence, at once protective and benevolent, is strong. There is a feeling of being completely at rest in this soothing presence. The breathing becomes very quiet and hardly perceptible. One is aware also that nourishment is being mysteriously and rhythmically drawn from the universal Life-force. Of course, there is no intellectual activity, no thinking, and no need of it. Instead, there is a k-n-o-w-i-n-g. There are no desires, no wishes, no wants. A happy peacefulness, almost verging on bliss, as human love might be without its passions and pettinesses, holds one in magical thrall. In its freedom from mental working and perturbation, from passional movement and emotional agitation, the condition bears something of infantile innocence. Hence Jesus' saying: “Except ye become as little children ye shall in no wise enter the Kingdom of Heaven.” But essentially it is a return to a spiritual womb, to being born again into a new world of being where at the beginning he is personally as helpless, as weak, and as dependent as the physical embryo itself.

In his own words:

“Writing, which is an exercise of the intellect to some, is an act of worship to me. I rise from my desk in the same mood as that in which I leave an hour of prayer in an old cathedral, or of meditation in a little wood . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 143

“P.B. as a private person does not count. There are hundreds of millions of such persons anyway. What is one man and his quest? P.B.’s personal experiences and views are not of any particular importance or special consequence. What happens to the individual man named P.B. is a matter of no account to anyone except himself. But what happens to the hundreds of thousands of spiritual seekers today who are following the same path that he pioneered is a serious matter and calls for prolonged consideration. Surely the hundreds of thousands of Western seekers who stand behind him and whom indeed, in one sense, he represents, do count. P.B. as a symbol of the scattered group of Western truth-seekers who, by following his writings so increasingly and so eagerly, virtually follow him also, does count. He personifies their aspirations, their repulsion from materialism and attraction toward mysticism, their interest in Oriental wisdom and their shepherdless state. As a symbol of this Western movement of thought, he is vastly greater than himself. In his mind and person the historic need for a new grasp of the contemporary spiritual problem found a plain-speaking voice . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 145

Learn more about Paul Brunton through articles at the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation web site

Ebook

Electronic versions of this book are available from all major (Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, etc.) and most smaller ebook vendors. Please don't try to order ebooks directly from us, as we are not yet able to deliver anything to you in a preferred electronic format.

Hardcover

We are currently out of stock of this volume in hardcover.

To see all our Paul Brunton titles, scroll down to The Complete Paul Brunton Opus below.

To see and/or order individual volumes in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, hover your mouse over the specific cover in the Notebooks section of Complete Paul Brunton Opus below, then click on Details in the box that appears within it.

Click here to see or order the complete set of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

About Paul Brunton

Paul Brunton helps us hear the melody behind the medley of today's "spiritual marketplace." His late writings raise the bar for what we can expect of spiritual teachings and teachers, and what we can do for ourselves. Born in London in 1898, he soon became a leading pioneer of much of what we now take for granted. He traveled widely throughout the world (long before it was fashionable) to meet living masters of various traditions with whom he then lived and studied. His eleven early books from 1934–1952 shared much of what he learned, and helped set the stage for dramatic east-west exchanges of the late 20th century. Paul Brunton left more than 10,000 pages of enormously helpful new work in notebooks he reserved for posthumous publication, much of which is now available as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. See "The Complete Paul Brunton Opus" in blue below to see his many works available on this site. You can also search on Paul Brunton in the search bar to browse the selections, or click on a link below for specific connections.

Click here for an article about Paul Brunton.

Click here for The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

To access small theme-based books compiled from Paul Brunton's writings, scroll down to Derived from the Notebooks below.

To access Paul Brunton's early writings, published from 1934–1952, scroll down to Paul Brunton's Early Works below.

To access commentaries on Paul Brunton and his work by his leading student, Anthony Damiani, as well as other writings about Paul Brunton and/or his work, scroll down to Commentaries and Reflections on Paul Brunton and His Work below.

The Complete Paul Brunton Opus:

Paul Brunton's most mature work, in the order he specified for posthumous publication.

Smaller books on popular/timely themes, developed from the Notebooks and published posthumously.

Paul Brunton's works published during his lifetime from 1934-1952

Commentaries/Reflections by other authors on Paul Brunton or his works.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)