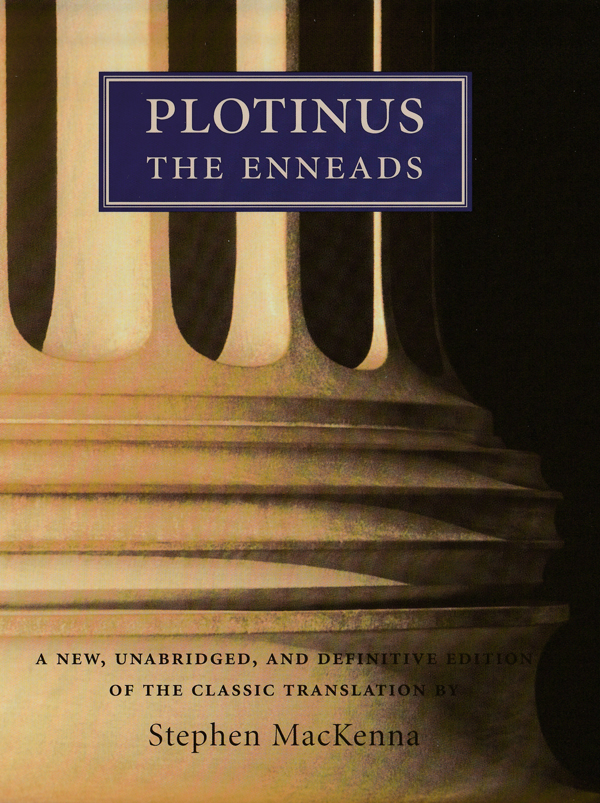

Plotinus: The Enneads

An unabridged, definitive edition of the classic Stephen MacKenna translation By MacKenna/Paige with Guthrie, Taylor, Armstrong

Retail/cover price: $75.00

Our price : $60.00

(You save $15.00!)

About this book:

Plotinus: The Enneads

An unabridged, definitive edition of the classic Stephen MacKenna translation

by MacKenna/Paige with Guthrie, Taylor, Armstrong

". . . a bible of beauty.” —James Hillman

“This truly great book is the source of much that is most precious in the whole Western spiritual tradition.” —Jacob Needleman

Subjects: Philosophy, Neoplatonism, Spirituality, Religion

6 x 9 cloth

768 pages

ISBN 10: 0-943914-55-8

ISBN 13: 978-0-943914-55-8

Book Details

“This truly great book is the source of much that is most precious in the whole Western spiritual tradition.” —Jacob Needleman

“MacKenna's translation of The Enneads continues to capture the 'voice' of Plotinus as no other English version does.” —Huston Smith

“For the rapture of its wild genius, MacKenna's Plotinus is the most inspiring and instructive single volume in my library . . . a source of the deepest ideas the mind can think, it is also a bible of beauty.” —James Hillman

This book is simply the most exalted translation of one of the finest products of the human mind. Our edition makes it truly “the thinking person's Plotinus” as well: Endnotes compare MacKenna's original translation with hundreds of debatable revisions made by editors in editions published after his death, and show how other major translators (A.H. Armstrong, K.S. Guthrie, Thomas Taylor) handle these same passages. Bonus: a detailed appendix from Anthony Damiani's groundbreaking work with The Enneads.

THE ENNEADS of Plotinus transport the reader, by what Pierre Hadot has called “an irresistible movement that defies analysis,” toward a fundamental but unutterable experience that transfigures everything. They are, as Hadot observes so beautifully, “spiritual exercises in which the soul sculpts herself — that is, purifies herself, simplifies herself, lifts herself to the plane of pure thought prior to transcending herself in ecstasy.”

“Withdraw into yourself and look,” Plotinus writes in Ennead I.6.9:

And if you do not find yourself beautiful yet, act as does the creator of a statue that is to be made beautiful: he cuts away here, he smoothes there, he makes this line lighter, this other purer, until a lovely face has grown upon his work. So do you also: cut away all that is excessive, straighten all that is crooked, bring light to all that is overcast, labour to make all one glow of beauty and never cease chiseling your statue, until there shall shine out on you from it the godlike splendour of virtue, until you shall see the perfect goodness surely established in the stainless shrine. When you know that you have become this perfect work, when you are self-gathered in the purity of your being, nothing now remaining that can shatter that inner unity, nothing from without clinging to the authentic man, when you find yourself wholly true to your essential nature, wholly that only veritable Light which is not measured by space, not narrowed to any circumscribed form . . . ever unmeasurable as something greater than all measure and more than all quantity — when you perceive that you have grown to this, you are now become very vision: now call up all your confidence, strike forward yet a step—you need a guide no longer — strain, and see.Here, when one has become an eye adapted to (or of sufficient likeness with) what is to be seen, this unutterable “experience” may begin. “When this consciousness takes hold of a man,” Paul Brunton writes, “it takes him by surprise. Infinity is so utterly different from what he was experiencing a few minutes earlier that its wonder, its truth, its love fill him abruptly, as if in descent from the skies.” Stillness lends its eloquence to a mind struck speechless, and nothing can ever again be the same. Nothing is ever again devoid of the divine; yet neither does any thing fully capture or express the exquisite intimacy of this eternally new ever-presence that remains absolutely seamless, free, and beyond conception.

For most who glimpse it, the actual experience passes, but the urge to regain it — to make it an established state — becomes a driving force of their inner life. Communicating this unutterable state — at once immanent and transcendent — and forging a way to it for his readers, is Plotinus’ sole purpose. To accomplish it, he summons all the possibilities of the language and thought of his epoch, developing a unique and incomparable tonality for which there is no substitute.

To experience the powerful cogency of his reasoning, even to be thrilled by the elegant beauty of his expositions, one need not share or even grant initial validity to his mystical — or paramystical — perceptions. Yet the cogency and beauty do lend wings to the rational mind. A process begins whereby that mind can convince itself, rationally, of the need for such perceptions — and gradually allow deeper levels of one’s own being to emerge and deliver them.

Plotinus was vividly aware that the self, the true “I,” is not essentially of our common sensible world: yet he was equally aware that we do not have to leave this world to reclaim the spiritual dimensions of our being. His “spiritual world” is not a supra-terrestrial or supra-cosmic place from which the vastness of extended space and the density of bodies separate the true self. It is the inner topography of that self, whose discontinuous levels can be revealed immediately through profound inward communion. As John Deck points out in Nature, Contemplation, and the One, this dimension of realization “is not, except metaphorically, a world above the everyday world. It is the everyday world — not as experienced by sense, by opinion, or by discursive reasoning — but as known . . . by the best knowing power.” And Plotinus also knew, paradoxically, that he was most this (true) self when least his (ego) self.

Plotinus’ uncanny ability to exhibit and map a course to this state of perception and — more importantly — to inspire us to pursue it, is what makes the Enneads of such inestimable value to contemporary seekers. It is, at the same time, what makes these writings such an astonishing challenge to translate. This issue deserves explanation, as it is the basis for structuring the present edition as we have.

One level of difficulty: Plotinus wrote mainly for his own students, who had distinct advantages in recognizing the nuances of his particular usage of certain terms. Another: his inspiration frequently stretches language toward nearly inexpressible profundities, invoking the poetic dimension and “violating” the grammar of linear thought. A third: the Enneads are not a step-by-step sequence of teachings readily reducible to a linear system of notions; rather, each seems to unfold a specific intuition that is itself an aspect of an underlying — and unwritable — grand insight; without access to this grand insight that makes ultimate sense of each of its intuited or reasoned elements, certain passages simply cannot be made to yield their full meaning. The reader will see, for example, several places in the present edition where major translators differ greatly: holding them all together, rather than trying to choose which is “right,” will sometimes show a large idea of which each has grasped a legitimate and necessary part.

ABOUT THIS EDITION

Our inspiration for an edition such as this one comes from years of living with the Enneads as the core of a broadly diversified spiritual practice under the late Anthony Damiani (1922 – 1984), founder of Wisdom’s Goldenrod Center for Philosophic Studies in Valois, New York. Time and again Anthony found in Plotinus ideas, or fertile perspectives on ideas, that resolved apparent conflicts in the teachings of sages from various traditions, teachings that — at least in their extant English texts — lacked the metaphysical or mystical detail Plotinus provides.

Stephen Clark, in The Mysteries of Religion, writes of how “Great critics sometimes seem to understand a text better than the words before them quite explain, better even than the author: they are, as we say, ‘on the same wavelength’.” In the case of Anthony Damiani and Plotinus, Anthony often discovered more in the text than seemed readily apparent from the words a given translator provided. Working with him often yielded glimpses of what Stephen Clark calls “the Angel of the Book” — an intelligence present with but slightly beyond the imperfect medium of the words, with revelatory power much greater than the intellect. When an author is inspired by and a reader tunes in to this “angel,” the words become transparent. Where intellect may before have proffered a dozen possible meanings, the angel silences all but the one that mirrors its intent.

Anyone who has successfully translated inspired thought from one language to another knows that meeting a winged idea in its original language is often only half the task. The next is to fashion words in the new language that not only describe its body but also soar with its wings. The poetic dimension must be activated anew, perhaps with the help of the “angel” itself.

And this is where the Irish poet and self-taught Greek scholar Stephen MacKenna shines. More often than any of the other English translators, he speaks the “angel” of the Enneads. When he catches an exalted idea, he expresses it exquisitely. For this reason, Anthony Damiani nearly always chose the poet in MacKenna over all other translators as providing the words most fruitful to take into meditation. But it must also be admitted that when MacKenna missed, he often missed completely.

Stephen MacKenna, however, worked on only the first of the four editions that bear his name. The subsequent three editions include increasing numbers of changes made by B.S. Page and incorporated indistinguishably into the text. The vast majority of Page’s changes are unquestionably improvements, and the fourth edition is deservedly most scholars’ text of choice for the MacKenna translation of Plotinus.

Anthony Damiani generally preferred the fourth edition as well. Through my years of study with him, however, there were many times that he expressed a preference for MacKenna’s original translation over Page’s changes where the two men differ significantly on points of philosophical meaning. In many of these cases, the difference of meaning is quite dramatic; in others the meaning is the same, but some readers may find the first edition more clear.

With the MacKenna translation out of print, we decided not only to re-issue it but also to show what we consider some of the more significant — and debatable — differences between the original and fourth editions. This editorial dimension of the project began primarily for our own edification. In the process of a thorough line-by-line comparison of the first and fourth editions, however, we discovered many more noteworthy differences than we had expected. The importance of such an undertaking became increasingly obvious.

Each of the differences noted is one that merited discussion among the editors on the project. Though we did not always agree on whether or not to footnote a given passage, we ultimately took the fact of having such differences of opinion as reason enough to do so. In some cases we ultimately agree with Page, but think MacKenna’s original thought worthy of consideration. In many others we firmly believe that MacKenna’s translation is not only more profound but also more attuned with the Plotinian “grand insight.”

Having found so many significant contrasts, we chose to take yet a further step toward creating the book that many serious students of Plotinus would most like to have. In most of the passages involving what we consider debatable differences between MacKenna and Page, we also show how the same ideas are handled by other major translators and interpreters: A.H. Armstrong, Thomas Taylor, K.S. Guthrie, and, occasionally, John Deck.

Each of the other translations has unique and laudable virtues, and the serious student will eventually want to read them all. Each also brings a wealth of scholarship to bear on the text. In general, A.H. Armstrong is highly praised for his technical precision, fidelity to the Greek text in light of recent scholarship, clear explication of his reasons for occasionally introducing interpretive changes, and valuable commentary. Thomas Taylor is renowned for his philosophical profundity; though he translated only a third of the tractates, his footnotes firmly establish the overall Neoplatonic context of many important ideas. Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie is most generous in carefully spelling out his understanding of a given idea, and offers many valuable cross-references — both within the Enneads themselves and to other Platonic and Neoplatonic sources. And John Deck, though he translated only small sections of the writings, shows an astonishing grasp of the overall Plotinian vision in his own treatment of some difficult metaphysical details. Juxtaposing their various visions of debatable passages often rounds out an idea with a clarity that none delivers alone. In some cases, it simply puts the non-Greek reader in a more informed position to reflect upon what Plotinus may have intended.

As B.S. Page points out in his preface to the second edition of MacKenna’s work, MacKenna “was no friend of the scholiast, and would not easily have consented to have his version of Plotinus used as itself a text for notes and variants.” Footnoting the text could easily be, as Page observes, “strangely incompatible with MacKenna’s ceaseless striving for lucidity and elegance of presentation.” Agreeing with and trying to honor this perception, we have attempted to minimize our intrusion on MacKenna’s magical spell.

We run the fourth edition as our main text. The reader may profitably ignore, on first reading, the vertical bars and tiny superscripts defining passages for which endnotes are to be found at the end of each tractate. We have also attempted to minimize the number of endnotes: the vast majority of Page’s changes being unquestionably correct, we call attention only to a relatively small percentage of them. On more careful study in subsequent reading, however, the reader should find most of these endnotes helpful — some perhaps even illuminating.

The first three tractates of the sixth ennead have no notes at all. These sections were translated by B.S. Page even in the first edition; though there are many changes between the first and fourth editions, these are changes Page made in his own work, not in MacKenna’s.

We hope that this edition will be a welcome contribution to the growing “Plotinian revival” and East-West spiritual dialogue. It has been a most satisfying project to work on. Much of which we were only partially aware through the years of working with Anthony Damiani has crystallized in the process of assembling it.

We offer it not as a be-all-and-end-all edition of Plotinus, simply as the most definitive edition of the MacKenna edition to date. The continuing dialogue of which it is a part is of inestimable value. Such dialogue, appropriately conducted, becomes a genuine spiritual practice in itself, expressing the ongoing life of the tradition of wisdom-knowledge.

In the spirit of further contributing to that dialogue, we have also added an appendix at the end of the book. It introduces key elements of one fertile perspective on the Plotinian “grand insight.” We are most grateful to Anthony Damiani for having exposed us to this perspective, and hope that it will prove useful to others who approach the Enneads as one of the greatest literary and philosophical masterpieces of all time.

This edition has come about through the combined volunteer efforts of many people. I am most grateful to more than twenty individuals associated with Wisdom’s Goldenrod and the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation for reproducing, carefully proofreading, and correcting the fourth-edition main text; for an exacting, line-by-line comparison of the first and fourth editions to identify all differences; for extensive and much-needed assistance in comparing these differences with those other translations and selecting which ones to footnote; and for essential financial assistance toward the cost of its publication. Thanks to this remarkable coming-together of so many highly motivated people, this edition has come to print despite the numerous difficulties besetting such idealistic publishing efforts at the present time.

I am also most grateful to James Hillman for his initial suggestion of comparing debatable differences to the A.H. Armstrong translation, which we subsequently developed to include other translations as well; to Huston Smith, Jacob Needleman, and Robert Bly for their enthusiastic support in the early stages of conceiving this project; to Anne Kilgore of Paperwork for skillful design and diligent production of the text and cover; and to George Whipple of Cornell University Press for valuable production advice and assistance.

Paul Cash

Director, Larson Publications

“This truly great book is the source of much that is most precious in the whole Western spiritual tradition—whether one’s interest is scholarly or whether one is seeking support for one’s own spiritual search.” —Jacob Needleman, author of The American Soul

“Out of Plotinus have come so many Yeats poems that I would love him for that alone. MacKenna’s translations of his words are ingenious, gorgeous, and Irish. We need to celebrate your putting his translation back into print.” —Robert Bly

“I first read MacKenna’s Plotinus in my twenties and I think no book ever had such a transforming influence on my life.” —Kathleen Raine

“MacKenna's translation of The Enneads continues to capture the 'voice' of Plotinus as no other English version does. . . . Time and again MacKenna’s Plotinus leaves the reader feeling exalted.” —Huston Smith

“For the rapture of its wild genius, MacKenna's Plotinus has been for near to forty years the most inspiring and instructive single volume in my library. It is a source of the deepest ideas the mind can think; it is also a bible of beauty.” —James Hillman

“I tell my students this is the edition to get.” —S.H. Nasr

From Ennead 1.6 Beauty, tractates 8, 9

8. But what must we do? How lies the path? How come to vision of the inaccessible Beauty, dwelling as if in consecrated precincts, apart from the common ways where all may see, even the profane?

He that has the strength, let him arise and withdraw into himself, foregoing all that is known by the eyes, turning away for ever from the material beauty that once made his joy. When he perceives those shapes of grace that show in body, let him not pursue: he must know them for copies, vestiges, shadows, and hasten away towards That they tell of. For if anyone follow what is like a beautiful shape playing over water — is there not a myth telling in symbol of such a dupe, how he sank into the depths of the current and was swept away to nothingness? So too, one that is held by material beauty and will not break free shall be precipitated, not in body but in Soul, down to the dark depths loathed of the Intellective-Being, where, blind even in the Lower-World, he shall have commerce only with shadows, there as here.

‘Let us flee then to the beloved Fatherland’: this is the soundest counsel. But what is this flight? How are we to gain the open sea? For Odysseus is surely a parable to us when he commands the flight from the sorceries of Circe or Calypso — not content to linger for all the pleasure offered to his eyes and all the delight of sense filling his days.

The Fatherland to us is There whence we have come, and There is The Father. What then is our course, what the manner of our flight? This is not a journey for the feet; the feet bring us only from land to land; nor need you think of coach or ship to carry you away; all this order of things you must set aside and refuse to see: you must close the eyes and call instead upon another vision which is to be waked within you, a vision, the birth-right of all, which few turn to use.

9. And this inner vision, what is its operation?

Newly awakened it is all too feeble to bear the ultimate splendour. Therefore the Soul must be trained — to the habit of remarking, first, all noble pursuits, then the works of beauty produced not by the labour of the arts but by the virtue of men known for their goodness: lastly, you must search the souls of those that have shaped these beautiful forms.

But how are you to see into a virtuous Soul and know its loveliness?

Withdraw into yourself and look. And if you do not find yourself beautiful yet, act as does the creator of a statue that is to be made beautiful: he cuts away here, he smoothes there, he makes this line lighter, this other purer, until a lovely face has grown upon his work. So do you also: cut away all that is excessive, straighten all that is crooked, bring light to all that is overcast, labour to make all one glow of beauty and never cease chiseling your statue, until there shall shine out on you from it the godlike splendour of virtue, until you shall see the perfect goodness surely established in the stainless shrine.

When you know that you have become this perfect work, when you are self-gathered in the purity of your being, nothing now remaining that can shatter that inner unity, nothing from without clinging to the authentic man, when you find yourself wholly true to your essential nature, wholly that only veritable Light which is not measured by space, not narrowed to any circumscribed form nor again diffused as a thing void of term, but ever unmeasurable as something greater than all measure and more than all quantity — when you perceive that you have grown to this, you are now become very vision: now call up all your confidence, strike forward yet a step — you need a guide no longer — strain, and see.

This is the only eye that sees the mighty Beauty. If the eye that adventures the vision be dimmed by vice, impure, or weak, and unable in its cowardly blenching to see the uttermost brightness, then it sees nothing even though another point to what lies plain to sight before it. To any vision must be brought an eye adapted to what is to be seen, and having some likeness to it. Never did eye see the sun unless it had first become sun-like, and never can the Soul have vision of the First Beauty unless itself be beautiful. . . .

From Ennead V.3, tractates 6, 7

. . . As long as we were Above, collected within the Intellectual nature, we were satisfied; we were held in the intellectual act; we had vision because we drew all into unity — for the thinker in us was the Intellectual Principle telling us of itself — and the Soul or mind was motionless, assenting to that act of its prior. But now that we are once more here — living in the secondary, the Soul — we seek for persuasive probabilities: it is through the image we desire to know the archetype.

Our way is to teach our Soul how the Intellectual-Principle exercises self-vision; the phase thus to be taught is that which already touches the intellective order, that which we call the understanding or intelligent Soul, indicating by the very name (dia-noia) that it is already of itself in some degree an Intellectual-Principle or that it holds its peculiar power through and from that Principle. This phase must be brought to understand by what means it has knowledge of the thing it sees and warrant for what it affirms: if it became what it affirms, it would by that fact possess self-knowing. All its vision and affirmation being in the Supreme or deriving from it — There where itself also is — it will possess self knowledge by its right as a Reason-Principle, claiming its kin and bringing all into accord with the divine imprint upon it.

The Soul therefore (to attain self-knowledge) has only to set this image (that is to say, its highest phase) alongside the veritable Intellectual-Principle which we have found to be identical with the truths constituting the objects of intellection, the world of Primals and Reality: for this Intellectual-Principle, by very definition, cannot be outside of itself, the Intellectual Reality: self-gathered and unalloyed, it is Intellectual-Principle through all the range of its being — for unintelligent intelligence is not possible — and thus it possesses of necessity self-knowing, as a being immanent to itself and one having for function and essence to be purely and solely Intellectual-Principle. This is no doer; the doer, not self-intent but looking outward, will have knowledge, in some kind, of the external, but, if wholly of this practical order, need have no self-knowledge; where, on the contrary, there is no action — and of course the pure Intellectual-Principle cannot be straining after any absent good — the intention can be only towards the self; at once self-knowing becomes not merely plausible but inevitable; what else could living signify in a being immune from action and existing in Intellect?

7. The contemplating of God, we might answer.

But to admit its knowing God is to be compelled to admit its self-knowing. It will know what it holds from God, what God has given forth or may; with this knowledge, it knows itself at the stroke, for it is itself one of those given things — in fact is all of them. Knowing God and His power, then, it knows itself, since it comes from Him and carries His power upon it; if, because here the act of vision is identical with the object, it is unable to see God clearly, then all the more, by the equation of seeing and seen, we are driven back upon that self-seeing and self-knowing in which seeing and thing seen are undistinguishably one thing. . . .

Nature, Contemplation, and the One, by John Deck

Astronoesis, by Anthony Damiani

Bio coming soon.

Book Details

“This truly great book is the source of much that is most precious in the whole Western spiritual tradition.” —Jacob Needleman

“MacKenna's translation of The Enneads continues to capture the 'voice' of Plotinus as no other English version does.” —Huston Smith

“For the rapture of its wild genius, MacKenna's Plotinus is the most inspiring and instructive single volume in my library . . . a source of the deepest ideas the mind can think, it is also a bible of beauty.” —James Hillman

This book is simply the most exalted translation of one of the finest products of the human mind. Our edition makes it truly “the thinking person's Plotinus” as well: Endnotes compare MacKenna's original translation with hundreds of debatable revisions made by editors in editions published after his death, and show how other major translators (A.H. Armstrong, K.S. Guthrie, Thomas Taylor) handle these same passages. Bonus: a detailed appendix from Anthony Damiani's groundbreaking work with The Enneads.

THE ENNEADS of Plotinus transport the reader, by what Pierre Hadot has called “an irresistible movement that defies analysis,” toward a fundamental but unutterable experience that transfigures everything. They are, as Hadot observes so beautifully, “spiritual exercises in which the soul sculpts herself — that is, purifies herself, simplifies herself, lifts herself to the plane of pure thought prior to transcending herself in ecstasy.”

“Withdraw into yourself and look,” Plotinus writes in Ennead I.6.9:

And if you do not find yourself beautiful yet, act as does the creator of a statue that is to be made beautiful: he cuts away here, he smoothes there, he makes this line lighter, this other purer, until a lovely face has grown upon his work. So do you also: cut away all that is excessive, straighten all that is crooked, bring light to all that is overcast, labour to make all one glow of beauty and never cease chiseling your statue, until there shall shine out on you from it the godlike splendour of virtue, until you shall see the perfect goodness surely established in the stainless shrine. When you know that you have become this perfect work, when you are self-gathered in the purity of your being, nothing now remaining that can shatter that inner unity, nothing from without clinging to the authentic man, when you find yourself wholly true to your essential nature, wholly that only veritable Light which is not measured by space, not narrowed to any circumscribed form . . . ever unmeasurable as something greater than all measure and more than all quantity — when you perceive that you have grown to this, you are now become very vision: now call up all your confidence, strike forward yet a step—you need a guide no longer — strain, and see.Here, when one has become an eye adapted to (or of sufficient likeness with) what is to be seen, this unutterable “experience” may begin. “When this consciousness takes hold of a man,” Paul Brunton writes, “it takes him by surprise. Infinity is so utterly different from what he was experiencing a few minutes earlier that its wonder, its truth, its love fill him abruptly, as if in descent from the skies.” Stillness lends its eloquence to a mind struck speechless, and nothing can ever again be the same. Nothing is ever again devoid of the divine; yet neither does any thing fully capture or express the exquisite intimacy of this eternally new ever-presence that remains absolutely seamless, free, and beyond conception.

For most who glimpse it, the actual experience passes, but the urge to regain it — to make it an established state — becomes a driving force of their inner life. Communicating this unutterable state — at once immanent and transcendent — and forging a way to it for his readers, is Plotinus’ sole purpose. To accomplish it, he summons all the possibilities of the language and thought of his epoch, developing a unique and incomparable tonality for which there is no substitute.

To experience the powerful cogency of his reasoning, even to be thrilled by the elegant beauty of his expositions, one need not share or even grant initial validity to his mystical — or paramystical — perceptions. Yet the cogency and beauty do lend wings to the rational mind. A process begins whereby that mind can convince itself, rationally, of the need for such perceptions — and gradually allow deeper levels of one’s own being to emerge and deliver them.

Plotinus was vividly aware that the self, the true “I,” is not essentially of our common sensible world: yet he was equally aware that we do not have to leave this world to reclaim the spiritual dimensions of our being. His “spiritual world” is not a supra-terrestrial or supra-cosmic place from which the vastness of extended space and the density of bodies separate the true self. It is the inner topography of that self, whose discontinuous levels can be revealed immediately through profound inward communion. As John Deck points out in Nature, Contemplation, and the One, this dimension of realization “is not, except metaphorically, a world above the everyday world. It is the everyday world — not as experienced by sense, by opinion, or by discursive reasoning — but as known . . . by the best knowing power.” And Plotinus also knew, paradoxically, that he was most this (true) self when least his (ego) self.

Plotinus’ uncanny ability to exhibit and map a course to this state of perception and — more importantly — to inspire us to pursue it, is what makes the Enneads of such inestimable value to contemporary seekers. It is, at the same time, what makes these writings such an astonishing challenge to translate. This issue deserves explanation, as it is the basis for structuring the present edition as we have.

One level of difficulty: Plotinus wrote mainly for his own students, who had distinct advantages in recognizing the nuances of his particular usage of certain terms. Another: his inspiration frequently stretches language toward nearly inexpressible profundities, invoking the poetic dimension and “violating” the grammar of linear thought. A third: the Enneads are not a step-by-step sequence of teachings readily reducible to a linear system of notions; rather, each seems to unfold a specific intuition that is itself an aspect of an underlying — and unwritable — grand insight; without access to this grand insight that makes ultimate sense of each of its intuited or reasoned elements, certain passages simply cannot be made to yield their full meaning. The reader will see, for example, several places in the present edition where major translators differ greatly: holding them all together, rather than trying to choose which is “right,” will sometimes show a large idea of which each has grasped a legitimate and necessary part.

ABOUT THIS EDITION

Our inspiration for an edition such as this one comes from years of living with the Enneads as the core of a broadly diversified spiritual practice under the late Anthony Damiani (1922 – 1984), founder of Wisdom’s Goldenrod Center for Philosophic Studies in Valois, New York. Time and again Anthony found in Plotinus ideas, or fertile perspectives on ideas, that resolved apparent conflicts in the teachings of sages from various traditions, teachings that — at least in their extant English texts — lacked the metaphysical or mystical detail Plotinus provides.

Stephen Clark, in The Mysteries of Religion, writes of how “Great critics sometimes seem to understand a text better than the words before them quite explain, better even than the author: they are, as we say, ‘on the same wavelength’.” In the case of Anthony Damiani and Plotinus, Anthony often discovered more in the text than seemed readily apparent from the words a given translator provided. Working with him often yielded glimpses of what Stephen Clark calls “the Angel of the Book” — an intelligence present with but slightly beyond the imperfect medium of the words, with revelatory power much greater than the intellect. When an author is inspired by and a reader tunes in to this “angel,” the words become transparent. Where intellect may before have proffered a dozen possible meanings, the angel silences all but the one that mirrors its intent.

Anyone who has successfully translated inspired thought from one language to another knows that meeting a winged idea in its original language is often only half the task. The next is to fashion words in the new language that not only describe its body but also soar with its wings. The poetic dimension must be activated anew, perhaps with the help of the “angel” itself.

And this is where the Irish poet and self-taught Greek scholar Stephen MacKenna shines. More often than any of the other English translators, he speaks the “angel” of the Enneads. When he catches an exalted idea, he expresses it exquisitely. For this reason, Anthony Damiani nearly always chose the poet in MacKenna over all other translators as providing the words most fruitful to take into meditation. But it must also be admitted that when MacKenna missed, he often missed completely.

Stephen MacKenna, however, worked on only the first of the four editions that bear his name. The subsequent three editions include increasing numbers of changes made by B.S. Page and incorporated indistinguishably into the text. The vast majority of Page’s changes are unquestionably improvements, and the fourth edition is deservedly most scholars’ text of choice for the MacKenna translation of Plotinus.

Anthony Damiani generally preferred the fourth edition as well. Through my years of study with him, however, there were many times that he expressed a preference for MacKenna’s original translation over Page’s changes where the two men differ significantly on points of philosophical meaning. In many of these cases, the difference of meaning is quite dramatic; in others the meaning is the same, but some readers may find the first edition more clear.

With the MacKenna translation out of print, we decided not only to re-issue it but also to show what we consider some of the more significant — and debatable — differences between the original and fourth editions. This editorial dimension of the project began primarily for our own edification. In the process of a thorough line-by-line comparison of the first and fourth editions, however, we discovered many more noteworthy differences than we had expected. The importance of such an undertaking became increasingly obvious.

Each of the differences noted is one that merited discussion among the editors on the project. Though we did not always agree on whether or not to footnote a given passage, we ultimately took the fact of having such differences of opinion as reason enough to do so. In some cases we ultimately agree with Page, but think MacKenna’s original thought worthy of consideration. In many others we firmly believe that MacKenna’s translation is not only more profound but also more attuned with the Plotinian “grand insight.”

Having found so many significant contrasts, we chose to take yet a further step toward creating the book that many serious students of Plotinus would most like to have. In most of the passages involving what we consider debatable differences between MacKenna and Page, we also show how the same ideas are handled by other major translators and interpreters: A.H. Armstrong, Thomas Taylor, K.S. Guthrie, and, occasionally, John Deck.

Each of the other translations has unique and laudable virtues, and the serious student will eventually want to read them all. Each also brings a wealth of scholarship to bear on the text. In general, A.H. Armstrong is highly praised for his technical precision, fidelity to the Greek text in light of recent scholarship, clear explication of his reasons for occasionally introducing interpretive changes, and valuable commentary. Thomas Taylor is renowned for his philosophical profundity; though he translated only a third of the tractates, his footnotes firmly establish the overall Neoplatonic context of many important ideas. Kenneth Sylvan Guthrie is most generous in carefully spelling out his understanding of a given idea, and offers many valuable cross-references — both within the Enneads themselves and to other Platonic and Neoplatonic sources. And John Deck, though he translated only small sections of the writings, shows an astonishing grasp of the overall Plotinian vision in his own treatment of some difficult metaphysical details. Juxtaposing their various visions of debatable passages often rounds out an idea with a clarity that none delivers alone. In some cases, it simply puts the non-Greek reader in a more informed position to reflect upon what Plotinus may have intended.

As B.S. Page points out in his preface to the second edition of MacKenna’s work, MacKenna “was no friend of the scholiast, and would not easily have consented to have his version of Plotinus used as itself a text for notes and variants.” Footnoting the text could easily be, as Page observes, “strangely incompatible with MacKenna’s ceaseless striving for lucidity and elegance of presentation.” Agreeing with and trying to honor this perception, we have attempted to minimize our intrusion on MacKenna’s magical spell.

We run the fourth edition as our main text. The reader may profitably ignore, on first reading, the vertical bars and tiny superscripts defining passages for which endnotes are to be found at the end of each tractate. We have also attempted to minimize the number of endnotes: the vast majority of Page’s changes being unquestionably correct, we call attention only to a relatively small percentage of them. On more careful study in subsequent reading, however, the reader should find most of these endnotes helpful — some perhaps even illuminating.

The first three tractates of the sixth ennead have no notes at all. These sections were translated by B.S. Page even in the first edition; though there are many changes between the first and fourth editions, these are changes Page made in his own work, not in MacKenna’s.

We hope that this edition will be a welcome contribution to the growing “Plotinian revival” and East-West spiritual dialogue. It has been a most satisfying project to work on. Much of which we were only partially aware through the years of working with Anthony Damiani has crystallized in the process of assembling it.

We offer it not as a be-all-and-end-all edition of Plotinus, simply as the most definitive edition of the MacKenna edition to date. The continuing dialogue of which it is a part is of inestimable value. Such dialogue, appropriately conducted, becomes a genuine spiritual practice in itself, expressing the ongoing life of the tradition of wisdom-knowledge.

In the spirit of further contributing to that dialogue, we have also added an appendix at the end of the book. It introduces key elements of one fertile perspective on the Plotinian “grand insight.” We are most grateful to Anthony Damiani for having exposed us to this perspective, and hope that it will prove useful to others who approach the Enneads as one of the greatest literary and philosophical masterpieces of all time.

This edition has come about through the combined volunteer efforts of many people. I am most grateful to more than twenty individuals associated with Wisdom’s Goldenrod and the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation for reproducing, carefully proofreading, and correcting the fourth-edition main text; for an exacting, line-by-line comparison of the first and fourth editions to identify all differences; for extensive and much-needed assistance in comparing these differences with those other translations and selecting which ones to footnote; and for essential financial assistance toward the cost of its publication. Thanks to this remarkable coming-together of so many highly motivated people, this edition has come to print despite the numerous difficulties besetting such idealistic publishing efforts at the present time.

I am also most grateful to James Hillman for his initial suggestion of comparing debatable differences to the A.H. Armstrong translation, which we subsequently developed to include other translations as well; to Huston Smith, Jacob Needleman, and Robert Bly for their enthusiastic support in the early stages of conceiving this project; to Anne Kilgore of Paperwork for skillful design and diligent production of the text and cover; and to George Whipple of Cornell University Press for valuable production advice and assistance.

Paul Cash

Director, Larson Publications

“This truly great book is the source of much that is most precious in the whole Western spiritual tradition—whether one’s interest is scholarly or whether one is seeking support for one’s own spiritual search.” —Jacob Needleman, author of The American Soul

“Out of Plotinus have come so many Yeats poems that I would love him for that alone. MacKenna’s translations of his words are ingenious, gorgeous, and Irish. We need to celebrate your putting his translation back into print.” —Robert Bly

“I first read MacKenna’s Plotinus in my twenties and I think no book ever had such a transforming influence on my life.” —Kathleen Raine

“MacKenna's translation of The Enneads continues to capture the 'voice' of Plotinus as no other English version does. . . . Time and again MacKenna’s Plotinus leaves the reader feeling exalted.” —Huston Smith

“For the rapture of its wild genius, MacKenna's Plotinus has been for near to forty years the most inspiring and instructive single volume in my library. It is a source of the deepest ideas the mind can think; it is also a bible of beauty.” —James Hillman

“I tell my students this is the edition to get.” —S.H. Nasr

From Ennead 1.6 Beauty, tractates 8, 9

8. But what must we do? How lies the path? How come to vision of the inaccessible Beauty, dwelling as if in consecrated precincts, apart from the common ways where all may see, even the profane?

He that has the strength, let him arise and withdraw into himself, foregoing all that is known by the eyes, turning away for ever from the material beauty that once made his joy. When he perceives those shapes of grace that show in body, let him not pursue: he must know them for copies, vestiges, shadows, and hasten away towards That they tell of. For if anyone follow what is like a beautiful shape playing over water — is there not a myth telling in symbol of such a dupe, how he sank into the depths of the current and was swept away to nothingness? So too, one that is held by material beauty and will not break free shall be precipitated, not in body but in Soul, down to the dark depths loathed of the Intellective-Being, where, blind even in the Lower-World, he shall have commerce only with shadows, there as here.

‘Let us flee then to the beloved Fatherland’: this is the soundest counsel. But what is this flight? How are we to gain the open sea? For Odysseus is surely a parable to us when he commands the flight from the sorceries of Circe or Calypso — not content to linger for all the pleasure offered to his eyes and all the delight of sense filling his days.

The Fatherland to us is There whence we have come, and There is The Father. What then is our course, what the manner of our flight? This is not a journey for the feet; the feet bring us only from land to land; nor need you think of coach or ship to carry you away; all this order of things you must set aside and refuse to see: you must close the eyes and call instead upon another vision which is to be waked within you, a vision, the birth-right of all, which few turn to use.

9. And this inner vision, what is its operation?

Newly awakened it is all too feeble to bear the ultimate splendour. Therefore the Soul must be trained — to the habit of remarking, first, all noble pursuits, then the works of beauty produced not by the labour of the arts but by the virtue of men known for their goodness: lastly, you must search the souls of those that have shaped these beautiful forms.

But how are you to see into a virtuous Soul and know its loveliness?

Withdraw into yourself and look. And if you do not find yourself beautiful yet, act as does the creator of a statue that is to be made beautiful: he cuts away here, he smoothes there, he makes this line lighter, this other purer, until a lovely face has grown upon his work. So do you also: cut away all that is excessive, straighten all that is crooked, bring light to all that is overcast, labour to make all one glow of beauty and never cease chiseling your statue, until there shall shine out on you from it the godlike splendour of virtue, until you shall see the perfect goodness surely established in the stainless shrine.

When you know that you have become this perfect work, when you are self-gathered in the purity of your being, nothing now remaining that can shatter that inner unity, nothing from without clinging to the authentic man, when you find yourself wholly true to your essential nature, wholly that only veritable Light which is not measured by space, not narrowed to any circumscribed form nor again diffused as a thing void of term, but ever unmeasurable as something greater than all measure and more than all quantity — when you perceive that you have grown to this, you are now become very vision: now call up all your confidence, strike forward yet a step — you need a guide no longer — strain, and see.

This is the only eye that sees the mighty Beauty. If the eye that adventures the vision be dimmed by vice, impure, or weak, and unable in its cowardly blenching to see the uttermost brightness, then it sees nothing even though another point to what lies plain to sight before it. To any vision must be brought an eye adapted to what is to be seen, and having some likeness to it. Never did eye see the sun unless it had first become sun-like, and never can the Soul have vision of the First Beauty unless itself be beautiful. . . .

From Ennead V.3, tractates 6, 7

. . . As long as we were Above, collected within the Intellectual nature, we were satisfied; we were held in the intellectual act; we had vision because we drew all into unity — for the thinker in us was the Intellectual Principle telling us of itself — and the Soul or mind was motionless, assenting to that act of its prior. But now that we are once more here — living in the secondary, the Soul — we seek for persuasive probabilities: it is through the image we desire to know the archetype.

Our way is to teach our Soul how the Intellectual-Principle exercises self-vision; the phase thus to be taught is that which already touches the intellective order, that which we call the understanding or intelligent Soul, indicating by the very name (dia-noia) that it is already of itself in some degree an Intellectual-Principle or that it holds its peculiar power through and from that Principle. This phase must be brought to understand by what means it has knowledge of the thing it sees and warrant for what it affirms: if it became what it affirms, it would by that fact possess self-knowing. All its vision and affirmation being in the Supreme or deriving from it — There where itself also is — it will possess self knowledge by its right as a Reason-Principle, claiming its kin and bringing all into accord with the divine imprint upon it.

The Soul therefore (to attain self-knowledge) has only to set this image (that is to say, its highest phase) alongside the veritable Intellectual-Principle which we have found to be identical with the truths constituting the objects of intellection, the world of Primals and Reality: for this Intellectual-Principle, by very definition, cannot be outside of itself, the Intellectual Reality: self-gathered and unalloyed, it is Intellectual-Principle through all the range of its being — for unintelligent intelligence is not possible — and thus it possesses of necessity self-knowing, as a being immanent to itself and one having for function and essence to be purely and solely Intellectual-Principle. This is no doer; the doer, not self-intent but looking outward, will have knowledge, in some kind, of the external, but, if wholly of this practical order, need have no self-knowledge; where, on the contrary, there is no action — and of course the pure Intellectual-Principle cannot be straining after any absent good — the intention can be only towards the self; at once self-knowing becomes not merely plausible but inevitable; what else could living signify in a being immune from action and existing in Intellect?

7. The contemplating of God, we might answer.

But to admit its knowing God is to be compelled to admit its self-knowing. It will know what it holds from God, what God has given forth or may; with this knowledge, it knows itself at the stroke, for it is itself one of those given things — in fact is all of them. Knowing God and His power, then, it knows itself, since it comes from Him and carries His power upon it; if, because here the act of vision is identical with the object, it is unable to see God clearly, then all the more, by the equation of seeing and seen, we are driven back upon that self-seeing and self-knowing in which seeing and thing seen are undistinguishably one thing. . . .

Nature, Contemplation, and the One, by John Deck

Astronoesis, by Anthony Damiani

About MacKenna/Paige with Guthrie, Taylor, Armstrong

Bio coming soon.

.jpg)