Emerson Here and Now

Ralph Waldo Emerson on Living an Original Relation to the Universe By Richard Geldard

.jpg)

Retail/cover price: $18.95

Our price : $15.16

(You save $3.79!)

About this book:

Emerson Here and Now

Ralph Waldo Emerson on Living an Original Relation to the Universe

by Richard Geldard

From the Foreword by Robert Richardson, author of: Emerson: The Mind on Fire

“Geldard understands the main thing, which is that Emerson is as alive, as pertinent, as urgent now as he was in his lifetime. We have only to reach out for the gifts which Emerson, like a new god on a new day, offers us."

Subjects: Spirituality, American Transcendentalism, Personal Transformation

6 x 9 trade paperback

190 pages

comprehensive index

ISBN 10:

ISBN 13: 978-1936012-96-1

Book Details

“Geldard understands the main thing, which is that Emerson is as alive, as pertinent, as urgent now as he was in his lifetime. We have only to reach out for the gifts which Emerson, like a new god on a new day, offers us. . . . for that spiritual work, Geldard’s is the most practical and useful handbook we have apart from Emerson’s own writings.” —Robert D. Richardson, Jr., author of Emerson, The Mind on Fire

Ralph Waldo Emerson devoted his entire life to inspiring each of us to discover, and showing us how to live, our own original, authentic relation to the universe. Emerson Here and Now, a 30th anniversary edition/celebration of Geldard’s finest book (first published as The Esoteric Emerson) helps us do just that. It is a great gift to a new generation of Americans seeking uplift, inspiration, and their own inner strength.

Foreword

No one who has felt the life-changing pull of Emerson’s enormous planetary mind has ever doubted his power or his greatness, though we are often puzzled to know whether he is primarily a poet, an essayist, or a philosopher. Richard Geldard is not puzzled at all by this; he has written a book which plainly shows the essential Emerson to be a teacher, the Socrates of Concord, a man with a message that we need to hear today. Previous generations “beheld God and nature face to face,” Emerson says, and he adds, provocatively, that we moderns seem able only to see those things through the eyes of the earlier generations. “Why,” he asks—and the question is intended to shatter our complacency— “Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs?”

Emerson’s life was devoted to showing how one may still attain an original, that is to say, an authentic, relation to the universe, and Geldard’s book aims to focus and distill the famously dispersed Emerson and put his central teachings into the modern reader’s hand. Geldard understands the main thing, which is that Emerson is as alive, as pertinent, as urgent now as he was in his lifetime. We have only to reach out for the gifts which Emerson, like a new god on a new day, offers us.

Where to begin? “Where do we find ourselves?” is Emerson’s way of starting. “We awake,” he says, “and find ourselves on a stair; there are stairs below us, which we seem to have ascended; there are stairs above us, many a one, which go upward and out of sight” It is a scene from Piranesi’s Imaginary Prisons, where stairs spiral up and reel down, and end in blank walls, in mid-air, or in darkness. Emerson’s intended audience is not a crowd or a group, but always the solitary reader, imprisoned, it may be, by the past, or by family, or habit, or fear of the future. Where do we find ourselves? Not in the nineteenth century, not in Concord (or not only there), not among men only, nor among white people only. We find ourselves, says Emerson, one by one in the here and now. “We must set up the strong present tense against all the rumors of wrath, past or to come.”

Emerson’s central message, as William James understood it and as Van Wyck Brooks summed it up, is the same message that “has marked all the periods of revival, the early Christian Age and Luther’s age, Rousseau’s, Kant’s and Goethe’s, namely, that the innermost nature of things is congenial to the powers that men possess.” Six months after the death of his first child, Waldo, aged five, Emerson rose in his grief to write to a Quaker acquaintance in Baltimore, Solomon Corner, that he, Emerson, had got no further than his old conviction that the powers of the soul are commensurate with its needs, all experience to the contrary notwithstanding.”

If true, why is this not more quickly apparent to us? Because, as Emerson fully recognized, something has gone wrong. It is literally true, as Emerson says and as Geldard emphasizes, that each of us “is made of the same atoms as the world is.” “We are star-stuff,” as Carl Sagan liked to say. “Except for hydrogen,” he wrote, “all the atoms that make each of us up—the iron in our blood, the calcium in our bones, the carbon in our brains—were manufactured in red giant stars thousands of light years away in space and billions of years ago in time.” Each new person is a fresh assortment of atoms and, as Emerson says, “the power which resides in him is new in nature.” But we have lost our vital connections to our heritage, like the orphan in a Victorian novel, and our task is now for each of us to regain his or her proper place in the world. “The reason why the world lacks unity, and lies broken and in heaps,” says Emerson, “is because man is disunited with himself.”

The solution is self-reliance. “To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men, —that is genius.” Fair enough, we say, but how exactly does one go about gaining this belief? We expect Emerson to lead us through, say, a twelve-step program, forgetting that what Emerson has to give us is the source, the secret, the reason why twelve-step programs work in the first place. We want a solid, should I say material, program from Emerson, but the basic fact is that “the foundations of man are not in matter, but in spirit,” as Emerson flatly puts it in “Nature.” The vital principle, the source of power for the human being, is the soul.

Now this is precisely the strength of Richard Geldard’s book, that he fully and sympathetically understands this spiritual dimension in Emerson, just as Emerson honors and praises the work of other and earlier teachers of the same doctrine, such as Plotinus and Thomas Taylor. The Emersonian work we must do to be saved is spiritual work. And for that spiritual work, Geldard’s is the most practical and useful handbook we have apart from Emerson’s own writings. Geldard leads the reader to a solid grasp of such concepts as “lowly listening,” “opening the heart,” to how “the best we can say of God is the mind as it is known to us,” and finally to an understanding that courage, meaning “equality to the problem before us,” is possible for us too. Geldard restores Emerson to the position he held among his contemporaries, that of a “seer of a revolution in human self-recovery."

Emerson believes, and may bring us to believe, that we have it in us to lead better lives, that we too can “affect the quality of the day,” as his friend Henry Thoreau put it. And while all Emerson’s teaching is based on the importance and power of the spirit, the means and the results are often surprisingly tangible. Even such a statement as “hitch your wagon to a star,” which sounds impractical if beautiful, turns out to have an unexpected grounding in the real world. Emerson was thinking, when he wrote that phrase, about the tide-mills that used to exist in Boston and along the East Coast. A dam, with a mill and a water wheel, would be built across the mouth of a long narrow bay. The incoming tide would turn the wheel one way, the outgoing tide would turn it the other way; both ways ground grain and sawed wood, and it was all done by hitching the mill to the tides which are hitched to the moon. So Emerson means his spiritual advice literally when he says—and we must hear where the emphasis falls— “hitch your wagon to a star.” Richard Geldard will show you how to tie the hitch.

—Robert D. Richardson, author of Emerson: The Mind on Fire

At Faneuil Hall, Boston, June, 2003

"Geldard's knowledge and understanding of Emerson is second to none, including the inimitable Harold Bloom." —Robert Lamb, New York Journal of Books

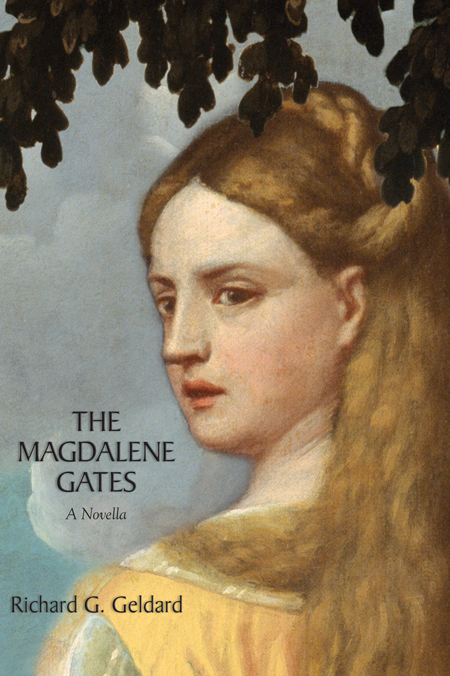

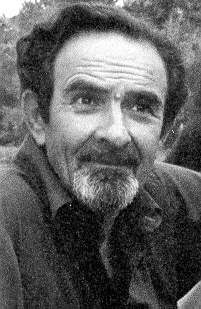

Richard Geldard is a full-time writer and lecturer living in New York City and the Hudson Valley. He is married to the artist and writer Astrid Fitzgerald.

Before turning to writing he was an educator, teaching English and philosophy at both the secondary, undergraduate and graduate levels. His most recent appointment was at the Pacifica Graduate Institute in Carpenteria, California, where he taught the Greek Mystery Religions. Prior to that he taught Greek Philosophy and The Science of Mind at Yeshiva College in New York, where he also supervised the General Studies program at the university’s boys' and girls' high schools.

He is a graduate of Bowdoin College, The Bread Loaf School of English at Middlebury College, and Stanford University, where he earned his doctorate in Dramatic Literature and Classics in 1972. He has also studied at St. John’s College, Oxford.

Geldard is the author of nine books, including studies of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Greek philosophy and culture. He is also a frequent lecturer. In June, 2003, and September, 2003, he was a featured speaker at Faneuil Hall in Boston as part of the Emerson Bicentennial Celebrations. In June, 2005, he was the Keynote speaker at the re-instatement of the Delphic Games in Delphi, Greece.

Dr. Geldard serves on three Boards of Directors: the Ralph Waldo Emerson Institute, the Friends of the Shawangunks and the World Sound Foundation.

Book Details

“Geldard understands the main thing, which is that Emerson is as alive, as pertinent, as urgent now as he was in his lifetime. We have only to reach out for the gifts which Emerson, like a new god on a new day, offers us. . . . for that spiritual work, Geldard’s is the most practical and useful handbook we have apart from Emerson’s own writings.” —Robert D. Richardson, Jr., author of Emerson, The Mind on Fire

Ralph Waldo Emerson devoted his entire life to inspiring each of us to discover, and showing us how to live, our own original, authentic relation to the universe. Emerson Here and Now, a 30th anniversary edition/celebration of Geldard’s finest book (first published as The Esoteric Emerson) helps us do just that. It is a great gift to a new generation of Americans seeking uplift, inspiration, and their own inner strength.

Foreword

No one who has felt the life-changing pull of Emerson’s enormous planetary mind has ever doubted his power or his greatness, though we are often puzzled to know whether he is primarily a poet, an essayist, or a philosopher. Richard Geldard is not puzzled at all by this; he has written a book which plainly shows the essential Emerson to be a teacher, the Socrates of Concord, a man with a message that we need to hear today. Previous generations “beheld God and nature face to face,” Emerson says, and he adds, provocatively, that we moderns seem able only to see those things through the eyes of the earlier generations. “Why,” he asks—and the question is intended to shatter our complacency— “Why should not we also enjoy an original relation to the universe? Why should not we have a poetry and philosophy of insight and not of tradition, and a religion by revelation to us, and not the history of theirs?”

Emerson’s life was devoted to showing how one may still attain an original, that is to say, an authentic, relation to the universe, and Geldard’s book aims to focus and distill the famously dispersed Emerson and put his central teachings into the modern reader’s hand. Geldard understands the main thing, which is that Emerson is as alive, as pertinent, as urgent now as he was in his lifetime. We have only to reach out for the gifts which Emerson, like a new god on a new day, offers us.

Where to begin? “Where do we find ourselves?” is Emerson’s way of starting. “We awake,” he says, “and find ourselves on a stair; there are stairs below us, which we seem to have ascended; there are stairs above us, many a one, which go upward and out of sight” It is a scene from Piranesi’s Imaginary Prisons, where stairs spiral up and reel down, and end in blank walls, in mid-air, or in darkness. Emerson’s intended audience is not a crowd or a group, but always the solitary reader, imprisoned, it may be, by the past, or by family, or habit, or fear of the future. Where do we find ourselves? Not in the nineteenth century, not in Concord (or not only there), not among men only, nor among white people only. We find ourselves, says Emerson, one by one in the here and now. “We must set up the strong present tense against all the rumors of wrath, past or to come.”

Emerson’s central message, as William James understood it and as Van Wyck Brooks summed it up, is the same message that “has marked all the periods of revival, the early Christian Age and Luther’s age, Rousseau’s, Kant’s and Goethe’s, namely, that the innermost nature of things is congenial to the powers that men possess.” Six months after the death of his first child, Waldo, aged five, Emerson rose in his grief to write to a Quaker acquaintance in Baltimore, Solomon Corner, that he, Emerson, had got no further than his old conviction that the powers of the soul are commensurate with its needs, all experience to the contrary notwithstanding.”

If true, why is this not more quickly apparent to us? Because, as Emerson fully recognized, something has gone wrong. It is literally true, as Emerson says and as Geldard emphasizes, that each of us “is made of the same atoms as the world is.” “We are star-stuff,” as Carl Sagan liked to say. “Except for hydrogen,” he wrote, “all the atoms that make each of us up—the iron in our blood, the calcium in our bones, the carbon in our brains—were manufactured in red giant stars thousands of light years away in space and billions of years ago in time.” Each new person is a fresh assortment of atoms and, as Emerson says, “the power which resides in him is new in nature.” But we have lost our vital connections to our heritage, like the orphan in a Victorian novel, and our task is now for each of us to regain his or her proper place in the world. “The reason why the world lacks unity, and lies broken and in heaps,” says Emerson, “is because man is disunited with himself.”

The solution is self-reliance. “To believe your own thought, to believe that what is true for you in your private heart is true for all men, —that is genius.” Fair enough, we say, but how exactly does one go about gaining this belief? We expect Emerson to lead us through, say, a twelve-step program, forgetting that what Emerson has to give us is the source, the secret, the reason why twelve-step programs work in the first place. We want a solid, should I say material, program from Emerson, but the basic fact is that “the foundations of man are not in matter, but in spirit,” as Emerson flatly puts it in “Nature.” The vital principle, the source of power for the human being, is the soul.

Now this is precisely the strength of Richard Geldard’s book, that he fully and sympathetically understands this spiritual dimension in Emerson, just as Emerson honors and praises the work of other and earlier teachers of the same doctrine, such as Plotinus and Thomas Taylor. The Emersonian work we must do to be saved is spiritual work. And for that spiritual work, Geldard’s is the most practical and useful handbook we have apart from Emerson’s own writings. Geldard leads the reader to a solid grasp of such concepts as “lowly listening,” “opening the heart,” to how “the best we can say of God is the mind as it is known to us,” and finally to an understanding that courage, meaning “equality to the problem before us,” is possible for us too. Geldard restores Emerson to the position he held among his contemporaries, that of a “seer of a revolution in human self-recovery."

Emerson believes, and may bring us to believe, that we have it in us to lead better lives, that we too can “affect the quality of the day,” as his friend Henry Thoreau put it. And while all Emerson’s teaching is based on the importance and power of the spirit, the means and the results are often surprisingly tangible. Even such a statement as “hitch your wagon to a star,” which sounds impractical if beautiful, turns out to have an unexpected grounding in the real world. Emerson was thinking, when he wrote that phrase, about the tide-mills that used to exist in Boston and along the East Coast. A dam, with a mill and a water wheel, would be built across the mouth of a long narrow bay. The incoming tide would turn the wheel one way, the outgoing tide would turn it the other way; both ways ground grain and sawed wood, and it was all done by hitching the mill to the tides which are hitched to the moon. So Emerson means his spiritual advice literally when he says—and we must hear where the emphasis falls— “hitch your wagon to a star.” Richard Geldard will show you how to tie the hitch.

—Robert D. Richardson, author of Emerson: The Mind on Fire

About Richard Geldard

At Faneuil Hall, Boston, June, 2003

"Geldard's knowledge and understanding of Emerson is second to none, including the inimitable Harold Bloom." —Robert Lamb, New York Journal of Books

Richard Geldard is a full-time writer and lecturer living in New York City and the Hudson Valley. He is married to the artist and writer Astrid Fitzgerald.

Before turning to writing he was an educator, teaching English and philosophy at both the secondary, undergraduate and graduate levels. His most recent appointment was at the Pacifica Graduate Institute in Carpenteria, California, where he taught the Greek Mystery Religions. Prior to that he taught Greek Philosophy and The Science of Mind at Yeshiva College in New York, where he also supervised the General Studies program at the university’s boys' and girls' high schools.

He is a graduate of Bowdoin College, The Bread Loaf School of English at Middlebury College, and Stanford University, where he earned his doctorate in Dramatic Literature and Classics in 1972. He has also studied at St. John’s College, Oxford.

Geldard is the author of nine books, including studies of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Greek philosophy and culture. He is also a frequent lecturer. In June, 2003, and September, 2003, he was a featured speaker at Faneuil Hall in Boston as part of the Emerson Bicentennial Celebrations. In June, 2005, he was the Keynote speaker at the re-instatement of the Delphic Games in Delphi, Greece.

Dr. Geldard serves on three Boards of Directors: the Ralph Waldo Emerson Institute, the Friends of the Shawangunks and the World Sound Foundation.

.jpg)

.jpg)