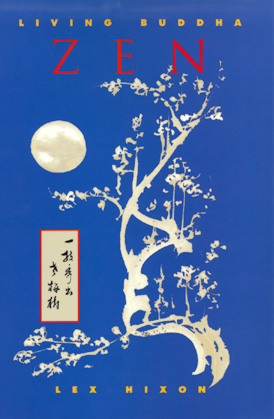

Living Buddha Zen

By Lex Hixon

Retail/cover price: $15.95

Our price : $12.76

(You save $3.19!)

About this book:

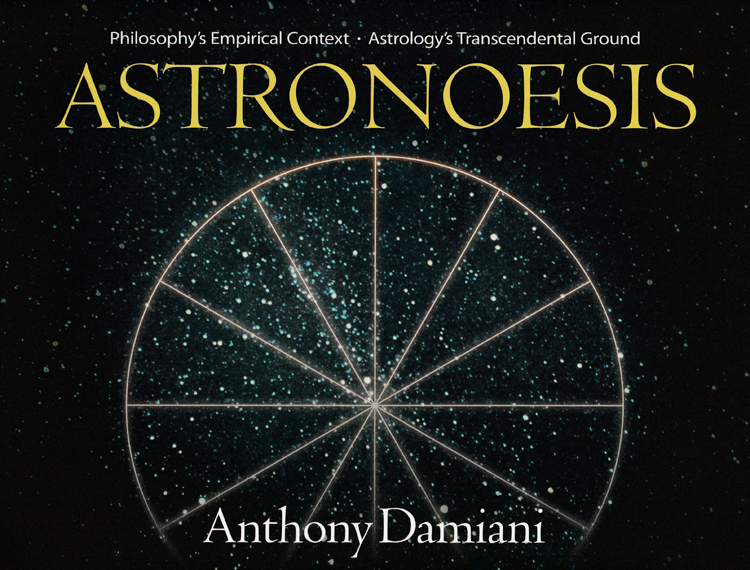

Living Buddha Zen

by Lex Hixon

Hixon's most amazing book.” —Robert Aitken, Roshi

A meticulously polished re-creation of the classic Denkoroku — 52 stories of how Buddha’s light flowed through masters to their successors.

Subjects: Spirituality, Buddhism

with Roshi Bernard Glassman

6 x 9, paperback

256 pages

ISBN 10: 0-943914-75-2

ISBN 13: 978-0-943914-75-6

Book Details

"Passionate . . . joyous, irrepressible, daring, announcing good news on every page." —Parabola

“A unique opportunity to embrace and absorb the wisdom of the Buddhas . . . an occasion of insight into Awakening.” —NAPRA Review

What happens in the moment of irreversible Awakening?

What leads up to it?

What follows?

Living Buddha Zen recreates 52 such ineffable moments, 52 “transmissions of the light” — from Shakyamuni Buddha continuously from master to successor. Hixon follows the original awakening impulse through India and China to the flowering of Soto Zen in Japan . . . and to his vision of how this same light circulates in the world today.

This is Lex’s final book, meticulously polished to his satisfaction in the months before his passing on. It is a modern re-creation, not a translation — in language that is fresh and alive — of the classic Japanese Denkoroku: The Record of Transmitting the Light.

The format follows that of the root text: koan, commentary, and concluding poem for each moment of sudden full illumination. Lex and his Zen mentor Roshi Bernard Tetsugen Glassman contemplated together and discussed each transmission.

Appreciation by Maezumi Roshi

Foreword by Helen Tworkov

Author's Introduction:

What is this Book?

Who Are These Living Buddhas?

Shakyamuni Buddha's Enlightenment

Wonderful Old Plum Tree Stands Deep in the Garden

Transmissions

One: Shakyamuni to Mahakashyapa

Two Clear Mirrors Facing Each Other outside Time

Two: Mahakashyapa to Ananda

Knock Down the Flagpole before the Gate!

Three: Ananda to Shanavasa

Buddha is Alive! Buddha is Alive!

Four: Shanavasa to Upagupta

Space is Consumed by Flaming Space

Five: Upagupta to Dhritaka

Not One Conventional Coin in this Treasury

Six: Dhritaka to Michaka

Hazy Moon of Spring

Seven: Michaka to Vasurnitra

There is No Need for an Empty Cup

Eight: Vasumitra to Buddhanandi

Do Not Imagine You are Going to Become a Still Pond

Nine: Buddhanandi to Buddhamitra

How Sweet These Seven Steps!

Ten: Buddhamitra to Parshva

Curling White Like Perpetually Breaking Waves

Eleven: Parshva to Punyayashas

Patience! Small Birds are Speaking!

Twelve: Punyayashas to Ashvaghosa

The Uncommon Red of the Peach Blossoms

Thirteen: Ashvaghosa to Kapimala

Pale Blue Mirror Ocean

Fourteen: Kapimala to Nagarjuna

It Simply Shines, Shines, Shines!

Fifteen: Nagarjuna to Aryadeva

White Crane Standing Still in Bright Moonlight

Sixteen: Aryadeva to Rahulata

This Delicious Fungus Grows Everywhere

Seventeen: Rahulata to Sanghanandi

Come Out of the Cave to Taste the Sweetness

Eighteen: Sanghanandi to Gayashata

Both Bell and Wind are the Silence of Great Mind

Nineteen: Gayashata to Kumarata

Bright Blue River Rushing in a Circle

Twenty: Kumarata to Jayata

Plum Tree Deep in the Garden Blossoms Spontaneously

Twenty-One: Jayata to Vasubandhu

Laughable Old Scarecrows

Twenty-Two: Vasubandhu to Manorhita

Ocean is Merging with Ocean

Twenty-Three: Manorhita to Haklenayashas

Come Out of the Sky, You Five Hundred Cranes!

Twenty-Four: Haklenayashas to Aryasinha

Whatever Merits I Attain Do Not Belong to Me

Twenty-Five: Aryasinha to Basiasita

Ancient Springtime Mind Light

Twenty-Six: Basiasita to Punyamitra

Just a Seldom Flowering Cactus

Twenty-Seven: Punyamitra to Prajnatara

Moonlight Swallows Moon

Twenty-Eight: Prajnatara to Bodhidharma

Though the Planet is Broad, There is No Other Path

Twenty-Nine: Bodhidharma to Hui-k'o

Allow the Entire Mindscape to Become a Smooth Wall

Thirty: Hui-k'o to Seng-ts'an

Do Not Fall into Inert Meditation

Thirty-One: Seng-ts'an to Tao-hsin

Glistening Serpent Never Entangled in Its Own Coils

Thirty-Two: Tao-hsin to Hung-jen

Light Can Be Poured Only Into Light

Thirty-Three: Hung-jen to Hui-neng

Woodcutter Realizes Instantly He Is A Diamond Cutter

Thirty-Four: Hui-neng to Ch'ing-yuan

How Can One Sew If the Needle Remains Shut in the Case?

Thirty-Five: Ch'ing-yuan to Shih-t'ou

Riding Effortlessly on a Large Green Turtle

Thirty-Six: Shih-t’ou to Yao-shan

Planting Flowers on a Smooth River Stone

Thirty-Seven: Yao-shan to Yun-yen

Same Wind Blowing for a Thousand Miles

Thirty-Eight: Yun-yen to Tung-shan

Sound of Wood Preaching Deep Underwater Words

Thirty-Nine: Tung-shan to Tao-ying

Whole Body Pours with Perspiration

Forty: Tao-ying to Tao-p'i

Pregnant jade Rabbit Enters Purple Sky

Forty-One: Tao-p'i to Kuan-chih

All is Great Peace from the Very Beginning

Forty-Two: Kuan-chih to Yuan-kuan

Deep Intimacy and Even Deeper Intimacy

Forty-Three: Yuan-kuan to Ta-yang

The Vermilion Sail is So Beautiful!

Forty-Four: Ta-yang to T'ou-tzu

Zen Master Dreams of Raising a Green Hawk

Forty-Five: T'ou-tzu to Tao-k'ai

I Am Terribly Ashamed to Be Called the Head of this Monastery

Forty-Six: Tao-k'ai to Tan-hsia

Now Melt Away Like Wax before the Fire!

Forty-Seven: Tan-hsia to Wu-k'ung

You Have Taken a Stroll in the Realm of Self-luminosity

Forty-Eight: Wu-k'ung to Tsung-chüeh

Dark Side of Moon Infinitely Vaster than Bright Side

Forty-Nine: Tsung-chüeh to Hsüeh-tou

Why Have I Never Encountered this Mystery Before?

Fifty: Hsüeh-tou to Ju-ching

In the Last Few Hundred Years, No Spiritual Guide Like Me Has Appeared

Fifty-One: Ju-ching to Dogen

The Terrible Thunder of Great Compassion

Fifty-Two: Dogen to Ejo

Subtly Piercing Every Atom of Japan

Lineage Chart of Buddha Ancestors from Shakyamuni Buddha to the Present

“No one, including many authors in Japan, has expressed these teachings with such distinctive style.” —Hakayu Taizan Maezumi, Roshi, Honolulu Diamond Sangha

“Living Buddha Zen is Hixon's most amazing book.” —Robert Aitken, Roshi

“Living Buddha Zen surprised me. This manuscript is not a new translation of an old classic at all! Rather it is an invitation to enter directly into the awakening process itself. Not by talking about it, but by allowing these stories to serve as doorways. Lex Hixon's expression of the Dharma is alive, immediate, universal — leaping with broad warmth over discriminations of gender and affiliation. As I read Living Buddha Zen, I am deeply nourished.” —Susan Ji-on Postal, Zen Priest, Empty Hand Zendo, Rye, NY

“Hixon emerges as a conservative keeper of the Zen flame — At the same time, however, he pushes past the known boundaries of his own cultural alphabet as well as the verbal conventions of Zen. Like the great Zen classics, this book embodies Zen as ‘the full moon way, complete from the very beginning.’” —Helen Tworkov, editor, Tricycle: The Buddhist Review

“Lex Hixon’s bold, free meditation on Keizan Zenji’s Denkoroku is an original and very welcome contribution.” —Peter Matthiessen, author, Snow Leopard; Nine-Headed Dragon River

“Passionate . . . joyous, irrepressible, daring, announcing good news on every page.” —Parabola

“Lex Hixon cuts through any notion of time or place to bring us the living lineage of the true Dharma Eye. His felicitous prose is like a sparkling brook; his closing poems are remarkable expressions of intimacy and delight. With its unimpeded warmth, its boundless generosity of spirit, Living Buddha Zen goes directly to the reader's heart. —Reverend Roko Sherry Chayat, Dharma Teacher and Director, Zen Center of Syracuse

“True to the Dharma name he received from Abbess Aoyama Sundo Roshi, Jikai or Ocean of Compassion, Lex Hixon, in a warm and all-embracing way offers an original and very stimulating interpretation of one of Zen's most important works, bringing it to the attention of a wider Western audience.” —Patricia Dai-En Bennage, Resident Senior Priest, Mt. Equity Zendo, Pennsylvania, Translator, Abbess Aoyama’s Zen Seeds

“The energies emanating from Lex Hixon's encounter with Zen Master Keizan are those of celebration, rejoicing, and ecstasy. This serves to take us to the heart of the matter.” —Nancy Baker, Professor of Philosophy, Sarah Lawrence College

Foreword, by Helen Twokov

Author of Zen in America

Editor, Tricycle: The Buddhist Review

I first met Lex Hixon more than twenty years ago in the antechamber of a house in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. We sat waiting our turns to meet privately with His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, a Tibetan lama renowned for his silent compassion and for his height. He was six foot seven. It was his first visit to the United States.

Over the following years, Lex and I would meet up again and again in circumstances which reflected the diverse channels through which the Buddha Dharma was flowing into the West. Together we have received teachings from Tibetan lamas, Vietnamese and Japanese masters, and American Zen teachers. We have encountered each other and the Dharma in hotel ballrooms, Bowery lofts, small apartments, elegant townhouses, a mansion in Riverdale, a waterfront warehouse in Yonkers. Each experience contained the quirky juxtapositions inevitable in the transmission of Dharma to the West.

Almost all these experiences evoked, at least for me, questions and more questions. For many years, I judged my own questioning harshly. I saw it as a sign of hopeless stupidity, of just not getting it. The fact that I had so many questions only seemed to indicate my attachment to a rational, faithless, logical way of understanding things. That my assessments were far from inaccurate made it all the more difficult for me to grasp that in Buddhist practice, ultimately, knowing nothing always eclipses knowing anything, and that questioning — or more specifically, the cultivation of a questioning mind — is integral to the practice itself.

Living Buddha Zen is a book of questions. In fact, it is a contemporary meditation on a Zen classic, Transmission of the Light, wherein the question — or koan — is used to transcend the parameters of rational thinking. Through complete absorption in the question itself, or, as it is said in Zen, by becoming the question, the practitioner uses a koan to dissolve the barriers that separate self and other, teacher and student. In this absence of any object or subject, “the transmission of light” occurs, and it is this illumination that Lex Hixon reflects, embodies, and communicates. But this is not a work of literal translation, for Hixon intertwines the traditional text with his personal investigation of the masters that make up the Zen line in which he himself is a lineage holder. Thus, Living Buddha Zen — as its title suggests — is a work of present history. By penetrating the all-encompassing wisdom minds of previous successors, Living Buddha Zen effects the collapse of time and space, making this journey, as Hixon says, both personal and planetary.

For Zen masters, Zen is life, this very universe in its entirety. And the transmission of light, upon which the authority and authenticity of the Zen tradition relies, transcends scripture, reason, words, and concepts. Nonetheless, Zen does have its own particular story, its distinct history and heroes, its location in time and place. Layered in its linguistic and cultural heritage, Zen arrived on Western shores in need of both literal and creative translators. This task of creating a new language for Zen in America provides an arena big enough to match Hixon's remarkable gifts.

Perhaps more than other modern contemplatives, Lex Hixon is the arch translator: from East to West, from old to new, from dead to living, from historical to contemporary, from the black and white calligraphic strokes of Zen to vibrant color and translucent imagery. And from the terse, often harsh and formidable language of the Zen patriarchs to a more universal and liquid language of love. In Living Buddha Zen, Hixon emerges as a conservative keeper of the Zen flame. At the same time, however, he pushes past the known boundaries of his own cultural alphabet as well as the verbal conventions of Zen, in order to retrieve from unknown territory a new way of retelling the classic teaching tales.

For all its idealization of silence — and perhaps because of it — Zen history has produced its fair share of written words. The Chinese masters of the Golden Era still inspire us, as they inspired Master Dogen, the thirteenth-century patriarch of Hixon’s own lineage. But Zen words have played different roles at different times. In Asian Zen — China, Japan, Korea — Zen classics and the Sutras of the Mahayana were studied almost exclusively in monasteries. These studies accompanied, inspired, and complemented a life devoted exclusively to attaining the very experiences indicated by the words. In traditional Asia, Zen words were not isolated from meditation, from working with a master, or from other aspects of daily life practice in a monastery Words may have echoed in the Void but never in a vacuum.

In the West, by contrast, words came first and played the central early role in our Zen history. In the absence of monasteries and even masters, in social contexts where sitting still was anathema and godless Reality blasphemy, books alone spread the Zen word. One cannot underestimate the transformative force that writings on Zen have had in this country. Convincingly, Hixon continues this literary heritage.

The first Zen master to visit the United States was Shoyen Shaku, the esteemed abbot of Engakuji. He came from Japan to Chicago in 1893 to attend the World's Parliament of Religions. He spoke no English and his letter of acceptance to the Parliament was written by his young student, D.T. Suzuki. Within a few years, Suzuki himself would be in the United States, living in Chicago at the home of Paul Carus, and working on translations with Carus at the Open Court Press.

By the 1950s, D.T. Suzuki had become the voice of Zen in the West. The word-magician who used language to point out the way of no-language, he talked to audiences in New York and London about the futility of talk and explained the inadequacy of explanation. A prolific and singular writer, Suzuki's books influenced a generation of Western intellectuals and fertilized the soil for subsequent generations of Western Zen practitioners. Not wanting to burden his curious but unprepared Western audience with the Japanese cultural formalities that infuse Zen method, Suzuki did not emphasize practices such as sitting and bowing, but concentrated instead on philosophy. A Zen master at work, Suzuki evoked just the right teachings for the level of his students through his intimate perception of the West.

It is beyond my imagination to picture the American Zen landscape without the ubiquitous presence of D.T. Suzuki. But there were other writers as well who preceded the practice centers, the zendos, and who helped ignite the Zen boom of the 1950s: the iconoclastic writings of Alan Watts, which challenged the monastic ideals of Asia; the extraordinary appeal of Jack Kerouac, whose work today is impacting a whole new generation; and Paul Reps’ widely circulated collected stories, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. It was the latter specifically, originally published as five separate volumes from 1934 to 1955, that provided Americans with their first taste of the tough and unsentimental flavor of the Zen tradition.

Zen developed in China as a radical alternative to the prevailing Buddhist schools. From the first century C.E. to the sixth, Chinese Buddhism advocated memorization and recitation of the sacred texts. This conservative approach depended on what had been time tested, esteeming the past over the present. Then came Bodhidharma, the blue-eyed monk who traveled East from India to China, only to manifest his perfect realization by facing a wall for nine years in silence. Today, Bodhidharma, revered as the first Zen patriarch, is still beloved, and still portrayed with the look of a pirate, rough and nasty, bearded, scowling, with a hoop in one ear. The enlarged look of his eyes is due to the absence of lids, for supposedly, the inclination of eyelids to close when sleepy interfered with Bodhidharma’s resolute sitting meditation, and so he cut them off. Whether or not this story is factual, it remains an indication of the radical Zen school of awakened masters that emerged. Bodhidharma’s successor, Hui-k'o in Chinese, Eka in Japanese, cut off his own arm as a testament to how serious he was about awakening. Eka succeeds Bodhidharma to become the second Zen patriarch.

After only two successions, between severed eyelids and an amputated arm, the uncompromising style of this Buddhist school could already be characterized by Barry Goldwater's memorable, Extremism in the name of liberty is no vice.

The liberty of which Senator Goldwater spoke referred to the American principles of democratic rule, while extremism argued in favor of the hapless effort to defend democracy by opposing Communist forces in Vietnam. Bodhidharma’s concerns with liberation were neither political nor dualistic, yet in both cases extremism is associated with shedding blood and fierce warriorship. This extremism is hard-edged, wounding, stoic, and sacrificial. In Zen history, as in war, the esthetic has been defined by men; and the intense muscularity of Zen remained very much part of the tradition inherited by both men and women in the West.

Eighty generations of lineage holders in the Soto Zen line have been patriarchs. Lex Hixon, as a Dharma heir of the American teacher, Tetsugen Glassman, is in the eighty-second generation. Beginning with Glassman Sensei’s eighty-first generation, through the blessings of his teacher, Taizan Maezumi Roshi, women have been granted full teaching authority. The passing of the patriarchal era lies mercifully in sight. For those concerned with this issue, Living Buddha Zen proves to be an unexpected ally.

Living Buddha Zen excels at the difficult task of speaking of silence in a language that expresses the authentic Zen terrain while releasing the imagery from its masculine stronghold. Here, the whip-cracking exchanges of bare-boned Zen discourse convert into generous, aromatic prose; tough love is replaced with unabashed devotion; the confidence of the disciple softens the hierarchical authority of the master. Here, love for the teacher, love for the Buddha Dharma, and love for life itself is emotionally charged, passionate, sensual. Tales of Zen life on the razor's edge are retold in language that is pliable and poetic. Pick a paragraph at random, and you may hear Rumi, Milarepa, or the Song of Solomon, but not Zen — at least not the Zen to which we have grown accustomed. You may even hear the voice of a woman.

Translation for Hixon is a process of transformation, translating from the inside out, from the heart and from his own understanding. If he has circumvented certain rules of the game, his choices have not been arbitrary. With a Ph.D. in religion from Columbia and seven books in print, he has spent thirty years investigating the initiatory lineages of various sacred traditions. The modern, secular, skeptical, scientific view has not been casually jettisoned by Hixon, but shed slowly, through trial and error, personal inquiry, reliable spiritual guidance, and fearless commitment to a naked vision.

Living Buddha Zen is not just a contemporary rendering of an old text, nor a lyrical account of one man's Zen story. Rather, like the great Zen classics, it embodies Zen in the manner of Master Dogen as “the full moon way, complete from the very beginning.” Living Buddha Zen is not a manual for enlightenment, yet it contains the essentialized teachings of Zen.

With Zen practice centers flourishing all over North America and the modem world, Hixon's audience is vastly different from D.T. Suzuki’s. So he offers not just an introduction, but an invitation to receive initiation and to pursue face-to-face study with a master, as he himself has done. As well, this book is a compendium of warnings against subtle forms of avoidance and inflation which masquerade as spiritual practice and realization.

As a genuine lineage holder, Hixon writes with the full empowerment of successive generations of adepts. But his special genius is to become the flexible vehicle through which this prodigious spiritual energy flows, while steadying himself in its midst long enough for his heart to find its voice for our benefit. This is the vow of the bodhisattva, and it affirms Living Buddha Zen as an authentic continuation of the transmission of light.

WHAT IS THIS BOOK?

This book is a union of personal and planetary history. To begin within the personal dimension, in 1991, when the October full moon, the orange harvest moon, was setting at dawn, on the day the Dalai Lama offered the ancient Tantric Kalachakra initiation at Madison Square Garden, I drove to meet my Zen master, Bernard Tetsugen Glassman Sensei. He is a Brooklyn kid who migrated West to the aerospace industry in southern California, becoming spiritual successor in 1976 to Taizan Maezumi Roshi, a Japanese Zen master living in Los Angeles. In 1979, Sensei Glassman returned to New York City to take his Zen seat here. I encountered him immediately.

So it was as old friends that Sensei and I sat together in radiant silence that early autumn morning in 1991, and then engaged in easy conversation, exploring the enlightenment experience of Shakyamuni Buddha. The essence of this meeting, and our subsequent fifty-two meetings over three years, tracing the transmission of Shakyamuni's enlightenment down fifty-two generations, is now recorded by Living Buddha Zen.

The present pages were born from Sensei Glassman’s intuition that I should write a book about our mutual study of these koan, these dramas of spiritual transmission between living Buddhas and their destined successors — twenty-eight generations in India, twenty-two generations in China, two generations in Japan. Sensei’s understanding of my need to write — a need which, as essentially a non-writing person, he does not share — reminds me of anthropologist Carlos Castaneda and his Yaqui Indian guide, Don Juan. The Native American sage realized that his modern apprentice could not get the rational mind out of the way unless he wrote voluminous field-notes.

The timeless sage in the present case, Bernard Glassman, emerged from modern culture with a Ph.D. in mathematics and an instinctive sense of business organization as a vehicle for social and spiritual action. Glassman is a Jewish Zen master who has vowed to end homelessness in Yonkers, the depressed community where he lives just north of New York City. He began from the entrepreneurial base of a gourmet bakery, staffed at first by his Zen students and now by inner city persons who have come through the Greystone Bakery job training program. The Sensei presently receives state grants to fund his programs for housing single mothers, infant day care, and now a residential AlDs facility for the homeless. Glassman has also founded the House of One People, an inner city community center where members of all religions can come to worship, meditate, and celebrate, both together and separately, in an atmosphere of social renewal and spiritual harmony.

These and many other projects are all undertaken in the unitive spirit of Shakyamuni Buddha's enlightenment. Glassman's own resolution of some one thousand Zen koan prepared him to develop a social vision rooted in the Buddhist principle of nonduality. Even his Zen teaching program, How to Raise an Ox, integrates the practical wisdom of the twelve-step movement, originally inspired by Alcoholics Anonymous, into the traditional Buddhist understanding of the path to enlightenment. Twice a year, Sensei leads a seven-day Street Retreat, when he and a few Zen students wholeheartedly join the homeless population of New York City, living in shelters and eating at soup kitchens, to which they later give anonymous financial contributions.

Bernard Glassman is hardly the romantic figure from another world, or worlds, that we encounter in the sorcerer Don Juan. Yet when seated face to face with Sensei in silence, an ancient wisdom-being is clearly manifest — mysterious, belonging to all worlds and to no world, a great being inseparable from the fifty-three Awakened Ones we approach through the pages of Living Buddha Zen.

The original work at the base of Living Buddha Zen is the fourteenth-century Japanese masterpiece by Keizan Zeriji, Denkoroku: The Record of Transmitting the Light. This text purports to trace the transmission from master to successor of the enlightenment of Shakyamuni Buddha through one thousand seven hundred years to the world-teacher, Dogen Zenji, in thirteenth-century Japan. Master Dogen is considered the father of the Soto Zen Order, which has twenty-five thousand temples and ten million practitioners in contemporary Japan. His seminal work, Shobogenzo: The Treasure House of the Eye of True Dharma, has profoundly inspired both Eastern and Western philosophers and spiritual practitioners during this century, after remaining in obscurity, even in its native land, for some seven hundred years. Master Keizan is considered the mother of Soto Zen, his Denkoroku being the reservoir or womb of the lineage.

The Denkoroku is a fifty-three stroke ink and brush drawing of essential Buddhist history. Seen more broadly, this text presents in the direct Zen manner the essential nature of awareness, the single Light celebrated by all ancient wisdom traditions. The Denkoroku is a work of art whose subject is sacred history. It is not historiography.

Even more than a work of art, this text is a vehicle for mutual study between Zen masters and their successors, honing the insight of each and insuring the actual continuation, without diminution, of Dogen Zenjis radical spiritual teaching, perpetual plenitude — the perfect awakeness, here and now, of all beings and worlds. This transmission of Light remains continuous throughout the unpredictable developments of planetary history, such as the transplanting of Zen from Japan to America and, from America, to the strange global landscape called the postmodern world.

These are some reasons why Sensei Glassman chose the Denkoroku as the text for our mutual study, preparing me for the Dharma transmission in which I will be invested with responsibility for pouring Light into the next generation. The formal ceremonies are scheduled to be celebrated in Japan and New York during 1995.

The model of Dharma transmission presented by the Denkoroku, one living Buddha for each generation, is symbolic. In actual fact, all fully awakened men and women in each generation constitute the living Buddha of that generation. According to the reckoning of his Soto lineage, Maezumi Roshi in Los Angeles represented the eightieth Buddha generation to descend from the Shakyamuni Buddha of ancient India, enlightened two thousand five hundred years ago. Glassman Sensei and other Western successors represent the eighty-first generation. Along with the next wave of successors, I represent the eighty-second Buddha generation. Members of these three contemporary Buddha generations — spiritual grandparents, spiritual parents, spiritual grandchildren — are scattered across the earth, some recognized by formal ceremony, others remaining hidden. Some are teaching, some are writing, others are simply waiting.

Also to be understood symbolically is the Denkoroku's single-pointed focus on the Soto lineage of Dogen Zenji, which seems to ignore the rich complexity of Buddhist history. This focus is the simplification of nature by the Zen artist, a simplification which permits the participant-observer to enter a much fuller, more profound experience of the landscape. Soto Zen here represents all realized Buddhist lineages and all wisdom traditions on the planet whose initiatory transmission of Light remains unbroken, providing a direct spiritual experience at the highest level of authenticity, not just a cultural inheritance or a romantic aspiration.

Glassman Sensei encouraged me at the beginning of our work together to experience direct encounter with Keizan Zenji, author of the Denkoroku. That is precisely what occurred. The six hundred ninety-one years that appeared to distance me from Master Keizan’s Zen talks melted away I encountered his text as living and breathing. His presence shone vividly as the brown-robed presence of my contemporary Zen master. I encountered with similar directness each of the fifty-two living Buddhas in the Denkoroku and the fountainhead of their lineage, Shakyamuni, whose enlightenment flows through and as them all. This enlightenment, or Light, suffers no diminution, and actually increases the breadth and profundity of its expression as Buddha generations pass.

To resolve any particular koan, to pass through any of the gateless gates along the pathless path of Zen, is simply to become this koan. Through the motherly encouragement and guidance of my ancient Japanese guide, Keizan Zenji, and my contemporary American guide, Tetsugen Glassman, I was somehow pushed, pulled, and inspired to become in turn each of these fifty-three living Buddhas. Without a qualified Zen master — in my case, two masters, one ancient, one contemporary — such a process would be impossible, even unimaginable.

Living Buddha Zen is my personal presentation of each koan, each drama of Dharma succession, as well as my personal commentary on each. These presentations and commentaries represent a fusion of my own perspectives as a practitioner of several sacred traditions, including the Tantric Buddhism of Tibet, with the perspectives of Keizan Zenji from fourteenth-century Japan and Glassman Sensei from our century. This fusion of insights cannot be analyzed into its component streams. As with any dish, some of the seasonings can be discerned, but we taste and enjoy it as a new experience, beyond any of its original ingredients. The ancient, the contemporary, and the timeless interact alchemically in these pages, which I would never claim as my own separate creation.

The same basic format followed by Keizan Zenji is followed here. First there is a condensed presentation of the ineluctable moment of transmitting Light, called koan, a presentation which I originally made orally to Tetsugen Glassman, opening our face-to-face meeting, or daisan. Then follows a free-flowing reflection on the transmission, called comment, composed from notes taken directly after my early morning Zen interviews-generous, loving conversations, not the staccato dialogues often associated with Zen. These records were later expanded, as I continued to reread the Zen talks of Master Keizan. Finally, I conclude each chapter as our ancient Japanese guide does by expressing koan and comment in a single poetic flash, called closing poem. These poems took shape inwardly, during or immediately following the Zen sitting, the Zen interview, and the Buddhist morning service—chanting, bowing, and offering incense, accompanied by deep bell, high bell, and wooden drum. Living Buddha Zen is not a book about Zen history, Zen philosophy, or Zen method. Nor is it autobiography. This book is simply a reservoir of Zen, envisioned by Dogen Zenji and others as the full moon way: Total Awakeness, complete from the very beginning.

What is this book? It is an invitation to the full moon way, the spontaneous awakeness which is total in every moment. It is an invitation to receive initiation and to pursue profound face-to-face study within any of the living wisdom traditions on the globe.

My gratitude flows primarily to my Zen master, Bernard Tetsugen Glassman, and to my spiritual grandfather, Hakuyu Taizan Maezumi who, along with his contemporary, Suzuki Roshi, and others, has helped to open the full moon way of Soto for America.

I joyfully acknowledge deep connection with another contemporary Soto full moon, Shundo Aoyama Roshi. Among the most prominent women Zen teachers in Japan, she is abbess of Aichi Women's Monastery in Nagoya. On the eve of the formal ceremony in New York City, 1983, when I became a senior student of Tetsugen Glassman, she gave me the Dharma name, Jikai, oceanic compassion.

I am also deeply grateful to Francis H. Cook, the scholar-practitioner whose accurate and sympathetic English translation, Denkoroku: The Record of Transmitting the Light, helped to make this entire experience possible. There are two other English translations of the Denkoroku by Western scholar-practitioners, indicating the immense importance and attraction of this text. The Denkoroku: The Record of the Transmission of the Light by Reverend Herbert Nearman O.B.C., was edited and contains an introduction by the prominent Western woman Zen teacher in America, British-born Jiyu-Kennett Roshi. The other translation is Transmission of Light by Thomas Cleary. These translations will provide inspiration to the interested reader. My version is not a translation but an assimilation. Yet Living Buddha Zen always aspires to remain loyal to the basic meaning of the Denkoroku and to the living spirit of its author, Keizan Zenji, fourth Buddha Ancestor of Japanese Soto, disciple of his own mother, profound devotee of the female Buddha, Kuan Yin, and initiate in the Japanese Tantric tradition.

Someone might ask, “How can your personal assimilation of this text have real value for someone else? Why not simply allow the accurate translations of the classical Japanese to stand alone?” This argument has the merit of simplicity, but somehow Buddha Dharma will not remain silent about itself. It continues to speak out, orally and in writing, through Buddha generation after Buddha generation. Sometimes the Dharma speech is completely authentic; other times, it remains veiled to various degrees by layers of personality and society. But the primordial urge to express truth continues to spring up spontaneously.

Living Buddha Zen is a manifestation of this urgency — boiling, fermenting, fructifying. At the very least, my study of Soto Zen teaching can inspire others to recognize that personal assimilation is possible — without knowing Japanese, without leaving aside social, family, and religious responsibility, without becoming someone who meditates for days or weeks on end, and without becoming so inflated as to deny personal limitations, to claim full enlightenment, or to claim any enlightenment whatsoever.

Living Buddha Zen is conceptually transparent. It will not further clutter the complex ideological, intellectual and religious landscape of modem times. It may even serve as antidote for this disease of complexity, as well as for the disease of over-simplification, two prominent modern maladies. Whether my book serves or does not serve, however, I had no choice but to write it.

WHO ARE THESE LIVING BUDDHAS?

Many of these living Buddhas, before awakening, were personal attendants of the previous living Buddhas, cherishing the selfless, responsive, transparent presence that the attendant’s role entails. One successor served as attendant for forty years under two living Buddhas before awakening into Buddhahood. Another continued to serve as attendant after his awakening, after his beloved master finally passed away, and even after his own biological death, declaring that his own unmarked tomb should be placed near the tomb of his beloved guide in the position of attendant.

These characteristics of the attendant, invisibility and pure attention, reflect throughout the lives of living Buddhas. At least two Awakened Ones regularly cleaned latrines after the unveiling of their inconceivably sublime nature — one remaining within the monastery, the other taking care of public latrines in the town, living there and speaking only the rough language of the common folk.

These two concealed their recognition as living Buddhas, as many other destined successors did. One living Buddha hid among hill tribes for ten years, constantly moving and changing his personal appearance to conceal his identity. Another waited sixty-seven years before revealing his revolutionizing wisdom. Ten years of concealment after being unveiled as living Buddhas was quite natural for these Awakened Ones. Some transmitted Light to hundreds or thousands, but most transmitted only to a few. Some taught the families of princes and emperors, but most refused invitations from places of temporal power, eating and dressing exactly like their monastic disciples or like the humble common people with whom they enjoyed associating. One gave his eye to a blind beggar.

Many of these destined inheritors of Buddhahood began the intensive process of unveiling during childhood or youth. One boy reached up and touched his own face while the Heart Sutra was being chanted — no eye, no ear, no tongue — astonishing his Sutra teacher with the confident Zen affirmation, “But I have eyes, ears, tongue!” Another destined successor, while his mother was washing a wound on the young boy's hand, stated in a straightforward manner, “My hand is a Buddha's hand.”

Mothers are immensely important to these successors, and are mentioned more prominently than fathers. Many mothers of these living Buddhas had dreams of the diamond beings destined to come forth from the wisdom womb of Mother Prajnaparamita, mystically unified with their own wombs. One mother dreamed she drank a liquid jewel on the night of conception. Another, already pregnant, dreamed of her future child standing on the summit of Mount Sumeru at the center of the visible and invisible cosmos, holding a golden ring and calmly reporting, “I am here.” Several bedchambers were filled with golden light at the moment of conception or birth. Wherever one successor walked, the earth turned a beautiful golden color.

In several instances, spiritual instructions from their mothers were the main source of inspiration for these destined successors to Buddhahood. Several renounced royal palaces or courtly careers particularly associated with their fathers, escaping by night into the wilderness of nondual Mother Wisdom, the realm of Goddess Prajnaparamita.

Some fathers and mothers voluntarily gave up their gifted children to the way of living Buddhahood upon hearing songs and affirmations of wisdom spring forth unexpectedly from the lips of these beloved young persons. One astonished father observed his mute, paralyzed son, fifty years old, become a successor to Buddhahood by taking his first steps toward the living Buddha and uttering his first words as a wisdom poem, Another destined successor was considered insane by his entire village as he wandered about moaning, night and day, carrying a gourd of wine. Yet another successor cut off his own arm to demonstrate radical commitment, an act that could not be considered sane by the standards of any culture.

Two among these successors to living Buddhahood were young homeless persons. One called himself nameless and the other immediately recognized his destined master from a previous eon. Two among these living Buddhas were executed by corrupt political authorities, and a third, by nonviolently extending his neck to the sword, touched the conscience of the emperor and received the royal reprieve. From the headless trunk of one precious Buddha body, milk gushed forth.

Many of these successors never studied Buddhism or practiced formal meditation, while others were profound scholars and intense monastic practitioners of Buddha Dharma from their youth. One successor insisted upon leaving home for a monastery at age six. Some began their relentless push to unveil intrinsic enlightenment later in life. One successor started practicing by becoming a monk at age sixty, remaining sleepless for three years until his awakening.

Some destined successors were already deeply realized when they approached their destined masters, others had more experiences to go through. One was a famous philosophical debater of the Buddhist Sutras of Liberation, another had delivered charismatic lectures on the Lotus Sutra since age seventeen. Some were profound meditators, realizers of emptiness, immersed in silence. One was a holy mendicant. Another was a shaman with thousands of followers. Other successors to living Buddhahood were adepts of various sacred traditions and yogic practices. One had read extensively in Taoist and Confucian philosophy. At least two lived in caves.

One successor studied the Sutras delivered by Buddhas from previous eons, scriptures preserved only on the subtle plane of the Naga kings. Another successor was born with left fist clenched, this disability only being healed by meeting the living Buddha and releasing to him a tiny miraculous gem from the Naga plane — a crystallized manifestation of Prajnaparamita, Perfect Nondual Wisdom.

Some who became living Buddhas continued to remain focused on the richness of Buddhist tradition, often resounding with Tantric overtones, while others polished all the colors of Buddhism from the rice of essential nature, leaving it brilliantly white. One living Buddha invited sincere non-Buddhists to practice in his monastery. In one instance recorded here, Shakyamuni Buddha opened the highest realization to a non-Buddhist practitioner.

Some who became living Buddhas were simple village persons, who received their destined masters in mud-walled huts. Others were princes or members of important families, who met with living Buddhas in palaces or beautiful old gardens. One cleansed the local temple of degenerate practices before he even reached the age of ten. One was constantly followed by a flock of cranes. Another was followed by a brilliant round mirror, visible only to those with spiritual sight.

One successor suffered from leprosy and was healed by his unveiling as living Buddha. Several successors were so transparent as to provide no details whatsoever about their existence prior to becoming living Buddhas. Several died in meditation, eyes open. One did not lie down to sleep for sixty years after his unveiling as a living Buddha. The body of at least one of these diamond beings remained incorrupt. When his tomb was opened by an earthquake, one year after death, the body was still sitting at ease in the position of meditation, only hair and nails had grown long.

At least one of these Awakened Ones was married and had a child — Shakyamuni Buddha, fountainhead of the lineage. Monastic sensibility may have prevented frank reporting of this dimension in the lives of other living Buddhas. Another dimension, even more obviously suppressed, is the existence of female living Buddhas. Even though the mothers of these fifty-three Awakened Ones are always near the center of their spiritual unfolding, the absence in the Denkoroku of living Buddhas who experience a woman's body and a woman's sensibility raises questions.

The fact that the living Buddha of each generation is constituted by all the fully awakened men and women of that generation permits the enlightened women of Buddhist history, and human history in general, to take their proper place. To one degree or another, however, awakened women are always concealed by male-oriented culture. But this pervasive pattern of male-orientation is changing. The continuous yet hidden stream of women’s spirituality is emerging. When future lineage trees are drawn, women's awakening will be openly recorded, their teaching gestures will be widely cherished, and their spiritual successors, both men and women, will be more numerous and more visible.

As we celebrate female practitioners and female living Buddhas from the past, as well as those from present and future who will be recognized and strongly supported by their surrounding cultures and religions, there is another perspective which must be considered. The living Buddhas are androgynous beings. Awakened Ones enjoy immediate conscious access to fatherly and motherly qualities, to sisterly and brother qualities, to the qualities of passionate female lover and passionate male lover. Female living Buddhas are therefore no more exclusively female than male living Buddhas are exclusively male. Whatever our cultural sense of maleness and femaleness may be, we will find in these fifty-three fluid and elusive sages of the Denkoroku a wonderfully broad spectrum of human response and expression.

Nor are living Buddhas purely transcendent beings — some mere essence of light without humanity, without personal integrity without history. Total Awakeness does not erase the experience of being human or being Indian, Chinese, Japanese, American. Living Buddhas are fully human. Being the most complete flowering of humanity, they are more passionately and compassionately human than we can imagine, for we are still lost in abstractions and patterns of avoidance that separate us from our true humanity.

The living Buddha can appreciate a cup of plain tea more profoundly than a museum curator can appreciate an ancient masterpiece. Why? The Awakened One is not curating, not defending or controlling, not separating past from present, not isolating museum, temple, or self from the miraculous flow of ordinary events.

This full humanity of the living Buddhas is precisely what demands that there be equal numbers of male and female Awakened Ones, whether they remain hidden or revealed. Gender experience and its nuances are a vivid dimension of full human experience.

The existence of female Buddhas, both celestial and earthly, was discovered and clearly proclaimed by Buddhist Tantra, beginning in India some fifteen centuries ago, but was strongly hinted at before that by the feminine nature of Prajnaparamita, Perfect Nondual Wisdom. In the Upanishads, the wisdom literature of ancient, pre-Buddhist India, the existence of fully awakened female sages is clearly documented.

However, the mainstream cultures of Buddhist lands, with the partial exception of Tantric India and Tibet, retained their fundamental male-orientation. For instance, none of the exalted female Buddhas of Tantra, such as the Vajradakini, ever entered Japan with the great wave of Tantric Buddhism called Shingon.

The spiritual principle of the equality of feminine and masculine has been irrefutably established by Tantric Buddhism and by other great sacred traditions, but, the social and religious implications of this principle have yet to be worked out with genuine completeness anywhere on the globe.

Let us consider once more the fifty-three living Buddhas presented by the Denkoroku. They are lepers, princes, nonviolent revolutionaries who face execution, shamans, yogis, deep meditators, scholars, debaters, cleaners of latrines, homeless children, the mute, the paralyzed, those who are apparently insane, mendicants, members of wealthy families, woodcutters, rice-huskers, persons spiritually awake from birth, anonymous persons who keep their backgrounds unknown, persons advanced in age as well as those who are surprisingly young, those with thousands of followers, those who conceal themselves among the common people, those in touch with subtle and divine beings on other planes of being, cave dwellers, village dwellers, city dwellers, adepts with miraculous powers, selfless attendants who regard themselves as utterly insignificant, devout Buddhists, members of other sacred traditions, practitioners without any religious identification.

Who are these living Buddhas? We are these living Buddhas! Whoever we are, however we are, whatever we are, wherever we are — in our naked awareness, unveiled, here and now! Welcome to the wonderful and auspicious realm where living Buddhas recognize and serve living Buddhas! Welcome to Living Buddha Zen!

Jikai

Lex Hixon

New York City

1995

“Lex Hixon was a pioneer in the spiritual renaissance in America over the last four decades.” —Allen Ginsberg, poet

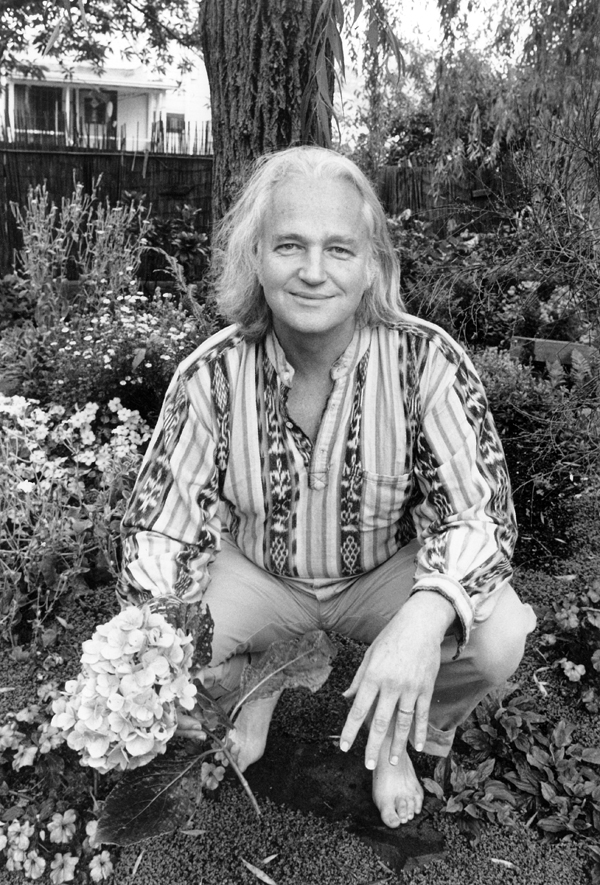

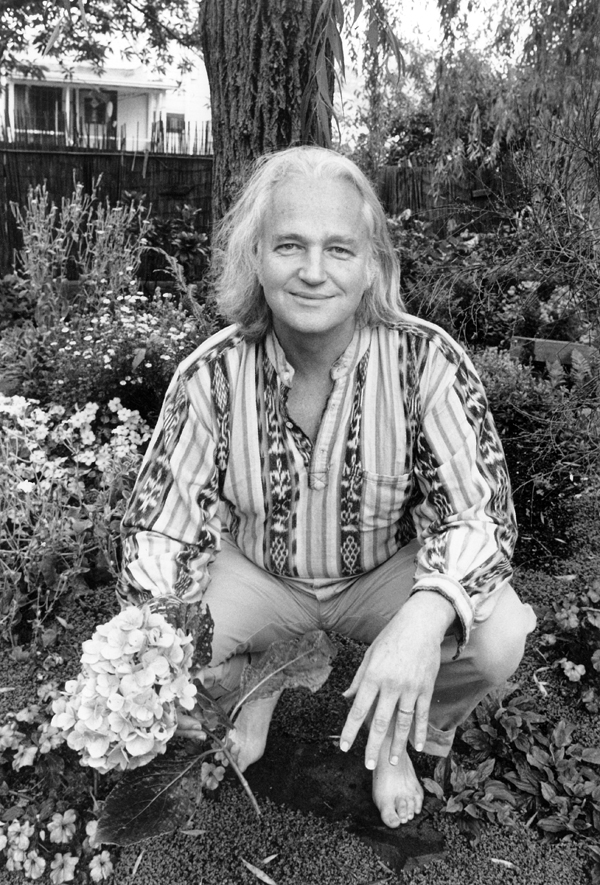

Lex Hixon (1941–1995) was truly an ambassador for the brighter possibilities of humanity’s future. An author of seven books, a practitioner/leader of five different religions, an accredited scholar (Ph.D. Columbia), and a contagiously passionate mystic, he left a priceless legacy for all who aspire to global community.

Originally a disciple of Swami Nikhilananda of the Ramakrishna Order, Lex came to life in five “parallel sacred worlds.” He was a member of the Eastern Orthodox church, became a teacher in a traditional Sufi lineage, and co-founded the Nur Ashki Jerrahi Sufi Order in the United States. For many years he hosted the radio program “In the Spirit” WBAI, on which he interviewed many religious teachers (including Mother Teresa of Calcutta and the Dalai Lama of Tibet) and was responsible for introducing their practices to many Americans. He was the founder of Free Spirit magazine. Shortly before his death, he was in the process of being ordained as a successor in the initiatory lineage of Dogen’s Soto Zen.

After Lex received his Ph.D. in World Religions from Columbia University in 1976 at age thirty-five, his first book was published by Doubleday in 1978, Coming Home: The Experience of Enlightenment in Sacred Traditions. This book, with its experiential bent and spirit of universality, has been widely recognized as a classic and is used regularly in college courses.

For more than thirty years, Lex traveled the globe making first-hand explorations of various initiatory lineages, always maintaining the clear and balanced overview he expressed in Coming Home. He began his traveling early, at age nineteen, when he lived and studied in South Dakota with Vine Deloria, Senior, a Lakota Sioux elder and Episcopal priest.

Beginning in 1980, Lex made a profound fifteen-year study of Islam and Sufism, which he reported in two of his books, Heart of the Koran and Atom from the Sun of Knowledge. His first-hand experience of Buddhism appears in Mother of the Buddhas: Meditation on the Prajnaparamita Sutra and Living Buddha Zen. His thirty-year involvement with the Divine Mother tradition of Bengal is documented in Great Swan: Meetings with Ramakrishna and Mother of the Universe: Visions of the Goddess and Tantric Hymns of Enlightenment. His final book was Living Buddha Zen, which he happily lived in good health long enough to hone to his full satisfaction.

Lex’s experience of being “orthodox in five different spiritual traditions” produced a unique philosophy, a “theory of relativity for religions.” His warm, joyful manner of teaching, celebrating, and encouraging spiritual seekers of all kinds touched thousands of lives.

Book Details

"Passionate . . . joyous, irrepressible, daring, announcing good news on every page." —Parabola

“A unique opportunity to embrace and absorb the wisdom of the Buddhas . . . an occasion of insight into Awakening.” —NAPRA Review

What happens in the moment of irreversible Awakening?

What leads up to it?

What follows?

Living Buddha Zen recreates 52 such ineffable moments, 52 “transmissions of the light” — from Shakyamuni Buddha continuously from master to successor. Hixon follows the original awakening impulse through India and China to the flowering of Soto Zen in Japan . . . and to his vision of how this same light circulates in the world today.

This is Lex’s final book, meticulously polished to his satisfaction in the months before his passing on. It is a modern re-creation, not a translation — in language that is fresh and alive — of the classic Japanese Denkoroku: The Record of Transmitting the Light.

The format follows that of the root text: koan, commentary, and concluding poem for each moment of sudden full illumination. Lex and his Zen mentor Roshi Bernard Tetsugen Glassman contemplated together and discussed each transmission.

Appreciation by Maezumi Roshi

Foreword by Helen Tworkov

Author's Introduction:

What is this Book?

Who Are These Living Buddhas?

Shakyamuni Buddha's Enlightenment

Wonderful Old Plum Tree Stands Deep in the Garden

Transmissions

One: Shakyamuni to Mahakashyapa

Two Clear Mirrors Facing Each Other outside Time

Two: Mahakashyapa to Ananda

Knock Down the Flagpole before the Gate!

Three: Ananda to Shanavasa

Buddha is Alive! Buddha is Alive!

Four: Shanavasa to Upagupta

Space is Consumed by Flaming Space

Five: Upagupta to Dhritaka

Not One Conventional Coin in this Treasury

Six: Dhritaka to Michaka

Hazy Moon of Spring

Seven: Michaka to Vasurnitra

There is No Need for an Empty Cup

Eight: Vasumitra to Buddhanandi

Do Not Imagine You are Going to Become a Still Pond

Nine: Buddhanandi to Buddhamitra

How Sweet These Seven Steps!

Ten: Buddhamitra to Parshva

Curling White Like Perpetually Breaking Waves

Eleven: Parshva to Punyayashas

Patience! Small Birds are Speaking!

Twelve: Punyayashas to Ashvaghosa

The Uncommon Red of the Peach Blossoms

Thirteen: Ashvaghosa to Kapimala

Pale Blue Mirror Ocean

Fourteen: Kapimala to Nagarjuna

It Simply Shines, Shines, Shines!

Fifteen: Nagarjuna to Aryadeva

White Crane Standing Still in Bright Moonlight

Sixteen: Aryadeva to Rahulata

This Delicious Fungus Grows Everywhere

Seventeen: Rahulata to Sanghanandi

Come Out of the Cave to Taste the Sweetness

Eighteen: Sanghanandi to Gayashata

Both Bell and Wind are the Silence of Great Mind

Nineteen: Gayashata to Kumarata

Bright Blue River Rushing in a Circle

Twenty: Kumarata to Jayata

Plum Tree Deep in the Garden Blossoms Spontaneously

Twenty-One: Jayata to Vasubandhu

Laughable Old Scarecrows

Twenty-Two: Vasubandhu to Manorhita

Ocean is Merging with Ocean

Twenty-Three: Manorhita to Haklenayashas

Come Out of the Sky, You Five Hundred Cranes!

Twenty-Four: Haklenayashas to Aryasinha

Whatever Merits I Attain Do Not Belong to Me

Twenty-Five: Aryasinha to Basiasita

Ancient Springtime Mind Light

Twenty-Six: Basiasita to Punyamitra

Just a Seldom Flowering Cactus

Twenty-Seven: Punyamitra to Prajnatara

Moonlight Swallows Moon

Twenty-Eight: Prajnatara to Bodhidharma

Though the Planet is Broad, There is No Other Path

Twenty-Nine: Bodhidharma to Hui-k'o

Allow the Entire Mindscape to Become a Smooth Wall

Thirty: Hui-k'o to Seng-ts'an

Do Not Fall into Inert Meditation

Thirty-One: Seng-ts'an to Tao-hsin

Glistening Serpent Never Entangled in Its Own Coils

Thirty-Two: Tao-hsin to Hung-jen

Light Can Be Poured Only Into Light

Thirty-Three: Hung-jen to Hui-neng

Woodcutter Realizes Instantly He Is A Diamond Cutter

Thirty-Four: Hui-neng to Ch'ing-yuan

How Can One Sew If the Needle Remains Shut in the Case?

Thirty-Five: Ch'ing-yuan to Shih-t'ou

Riding Effortlessly on a Large Green Turtle

Thirty-Six: Shih-t’ou to Yao-shan

Planting Flowers on a Smooth River Stone

Thirty-Seven: Yao-shan to Yun-yen

Same Wind Blowing for a Thousand Miles

Thirty-Eight: Yun-yen to Tung-shan

Sound of Wood Preaching Deep Underwater Words

Thirty-Nine: Tung-shan to Tao-ying

Whole Body Pours with Perspiration

Forty: Tao-ying to Tao-p'i

Pregnant jade Rabbit Enters Purple Sky

Forty-One: Tao-p'i to Kuan-chih

All is Great Peace from the Very Beginning

Forty-Two: Kuan-chih to Yuan-kuan

Deep Intimacy and Even Deeper Intimacy

Forty-Three: Yuan-kuan to Ta-yang

The Vermilion Sail is So Beautiful!

Forty-Four: Ta-yang to T'ou-tzu

Zen Master Dreams of Raising a Green Hawk

Forty-Five: T'ou-tzu to Tao-k'ai

I Am Terribly Ashamed to Be Called the Head of this Monastery

Forty-Six: Tao-k'ai to Tan-hsia

Now Melt Away Like Wax before the Fire!

Forty-Seven: Tan-hsia to Wu-k'ung

You Have Taken a Stroll in the Realm of Self-luminosity

Forty-Eight: Wu-k'ung to Tsung-chüeh

Dark Side of Moon Infinitely Vaster than Bright Side

Forty-Nine: Tsung-chüeh to Hsüeh-tou

Why Have I Never Encountered this Mystery Before?

Fifty: Hsüeh-tou to Ju-ching

In the Last Few Hundred Years, No Spiritual Guide Like Me Has Appeared

Fifty-One: Ju-ching to Dogen

The Terrible Thunder of Great Compassion

Fifty-Two: Dogen to Ejo

Subtly Piercing Every Atom of Japan

Lineage Chart of Buddha Ancestors from Shakyamuni Buddha to the Present

“No one, including many authors in Japan, has expressed these teachings with such distinctive style.” —Hakayu Taizan Maezumi, Roshi, Honolulu Diamond Sangha

“Living Buddha Zen is Hixon's most amazing book.” —Robert Aitken, Roshi

“Living Buddha Zen surprised me. This manuscript is not a new translation of an old classic at all! Rather it is an invitation to enter directly into the awakening process itself. Not by talking about it, but by allowing these stories to serve as doorways. Lex Hixon's expression of the Dharma is alive, immediate, universal — leaping with broad warmth over discriminations of gender and affiliation. As I read Living Buddha Zen, I am deeply nourished.” —Susan Ji-on Postal, Zen Priest, Empty Hand Zendo, Rye, NY

“Hixon emerges as a conservative keeper of the Zen flame — At the same time, however, he pushes past the known boundaries of his own cultural alphabet as well as the verbal conventions of Zen. Like the great Zen classics, this book embodies Zen as ‘the full moon way, complete from the very beginning.’” —Helen Tworkov, editor, Tricycle: The Buddhist Review

“Lex Hixon’s bold, free meditation on Keizan Zenji’s Denkoroku is an original and very welcome contribution.” —Peter Matthiessen, author, Snow Leopard; Nine-Headed Dragon River

“Passionate . . . joyous, irrepressible, daring, announcing good news on every page.” —Parabola

“Lex Hixon cuts through any notion of time or place to bring us the living lineage of the true Dharma Eye. His felicitous prose is like a sparkling brook; his closing poems are remarkable expressions of intimacy and delight. With its unimpeded warmth, its boundless generosity of spirit, Living Buddha Zen goes directly to the reader's heart. —Reverend Roko Sherry Chayat, Dharma Teacher and Director, Zen Center of Syracuse

“True to the Dharma name he received from Abbess Aoyama Sundo Roshi, Jikai or Ocean of Compassion, Lex Hixon, in a warm and all-embracing way offers an original and very stimulating interpretation of one of Zen's most important works, bringing it to the attention of a wider Western audience.” —Patricia Dai-En Bennage, Resident Senior Priest, Mt. Equity Zendo, Pennsylvania, Translator, Abbess Aoyama’s Zen Seeds

“The energies emanating from Lex Hixon's encounter with Zen Master Keizan are those of celebration, rejoicing, and ecstasy. This serves to take us to the heart of the matter.” —Nancy Baker, Professor of Philosophy, Sarah Lawrence College

Foreword, by Helen Twokov

Author of Zen in America

Editor, Tricycle: The Buddhist Review

I first met Lex Hixon more than twenty years ago in the antechamber of a house in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. We sat waiting our turns to meet privately with His Holiness Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche, a Tibetan lama renowned for his silent compassion and for his height. He was six foot seven. It was his first visit to the United States.

Over the following years, Lex and I would meet up again and again in circumstances which reflected the diverse channels through which the Buddha Dharma was flowing into the West. Together we have received teachings from Tibetan lamas, Vietnamese and Japanese masters, and American Zen teachers. We have encountered each other and the Dharma in hotel ballrooms, Bowery lofts, small apartments, elegant townhouses, a mansion in Riverdale, a waterfront warehouse in Yonkers. Each experience contained the quirky juxtapositions inevitable in the transmission of Dharma to the West.

Almost all these experiences evoked, at least for me, questions and more questions. For many years, I judged my own questioning harshly. I saw it as a sign of hopeless stupidity, of just not getting it. The fact that I had so many questions only seemed to indicate my attachment to a rational, faithless, logical way of understanding things. That my assessments were far from inaccurate made it all the more difficult for me to grasp that in Buddhist practice, ultimately, knowing nothing always eclipses knowing anything, and that questioning — or more specifically, the cultivation of a questioning mind — is integral to the practice itself.

Living Buddha Zen is a book of questions. In fact, it is a contemporary meditation on a Zen classic, Transmission of the Light, wherein the question — or koan — is used to transcend the parameters of rational thinking. Through complete absorption in the question itself, or, as it is said in Zen, by becoming the question, the practitioner uses a koan to dissolve the barriers that separate self and other, teacher and student. In this absence of any object or subject, “the transmission of light” occurs, and it is this illumination that Lex Hixon reflects, embodies, and communicates. But this is not a work of literal translation, for Hixon intertwines the traditional text with his personal investigation of the masters that make up the Zen line in which he himself is a lineage holder. Thus, Living Buddha Zen — as its title suggests — is a work of present history. By penetrating the all-encompassing wisdom minds of previous successors, Living Buddha Zen effects the collapse of time and space, making this journey, as Hixon says, both personal and planetary.

For Zen masters, Zen is life, this very universe in its entirety. And the transmission of light, upon which the authority and authenticity of the Zen tradition relies, transcends scripture, reason, words, and concepts. Nonetheless, Zen does have its own particular story, its distinct history and heroes, its location in time and place. Layered in its linguistic and cultural heritage, Zen arrived on Western shores in need of both literal and creative translators. This task of creating a new language for Zen in America provides an arena big enough to match Hixon's remarkable gifts.

Perhaps more than other modern contemplatives, Lex Hixon is the arch translator: from East to West, from old to new, from dead to living, from historical to contemporary, from the black and white calligraphic strokes of Zen to vibrant color and translucent imagery. And from the terse, often harsh and formidable language of the Zen patriarchs to a more universal and liquid language of love. In Living Buddha Zen, Hixon emerges as a conservative keeper of the Zen flame. At the same time, however, he pushes past the known boundaries of his own cultural alphabet as well as the verbal conventions of Zen, in order to retrieve from unknown territory a new way of retelling the classic teaching tales.

For all its idealization of silence — and perhaps because of it — Zen history has produced its fair share of written words. The Chinese masters of the Golden Era still inspire us, as they inspired Master Dogen, the thirteenth-century patriarch of Hixon’s own lineage. But Zen words have played different roles at different times. In Asian Zen — China, Japan, Korea — Zen classics and the Sutras of the Mahayana were studied almost exclusively in monasteries. These studies accompanied, inspired, and complemented a life devoted exclusively to attaining the very experiences indicated by the words. In traditional Asia, Zen words were not isolated from meditation, from working with a master, or from other aspects of daily life practice in a monastery Words may have echoed in the Void but never in a vacuum.

In the West, by contrast, words came first and played the central early role in our Zen history. In the absence of monasteries and even masters, in social contexts where sitting still was anathema and godless Reality blasphemy, books alone spread the Zen word. One cannot underestimate the transformative force that writings on Zen have had in this country. Convincingly, Hixon continues this literary heritage.

The first Zen master to visit the United States was Shoyen Shaku, the esteemed abbot of Engakuji. He came from Japan to Chicago in 1893 to attend the World's Parliament of Religions. He spoke no English and his letter of acceptance to the Parliament was written by his young student, D.T. Suzuki. Within a few years, Suzuki himself would be in the United States, living in Chicago at the home of Paul Carus, and working on translations with Carus at the Open Court Press.

By the 1950s, D.T. Suzuki had become the voice of Zen in the West. The word-magician who used language to point out the way of no-language, he talked to audiences in New York and London about the futility of talk and explained the inadequacy of explanation. A prolific and singular writer, Suzuki's books influenced a generation of Western intellectuals and fertilized the soil for subsequent generations of Western Zen practitioners. Not wanting to burden his curious but unprepared Western audience with the Japanese cultural formalities that infuse Zen method, Suzuki did not emphasize practices such as sitting and bowing, but concentrated instead on philosophy. A Zen master at work, Suzuki evoked just the right teachings for the level of his students through his intimate perception of the West.

It is beyond my imagination to picture the American Zen landscape without the ubiquitous presence of D.T. Suzuki. But there were other writers as well who preceded the practice centers, the zendos, and who helped ignite the Zen boom of the 1950s: the iconoclastic writings of Alan Watts, which challenged the monastic ideals of Asia; the extraordinary appeal of Jack Kerouac, whose work today is impacting a whole new generation; and Paul Reps’ widely circulated collected stories, Zen Flesh, Zen Bones. It was the latter specifically, originally published as five separate volumes from 1934 to 1955, that provided Americans with their first taste of the tough and unsentimental flavor of the Zen tradition.

Zen developed in China as a radical alternative to the prevailing Buddhist schools. From the first century C.E. to the sixth, Chinese Buddhism advocated memorization and recitation of the sacred texts. This conservative approach depended on what had been time tested, esteeming the past over the present. Then came Bodhidharma, the blue-eyed monk who traveled East from India to China, only to manifest his perfect realization by facing a wall for nine years in silence. Today, Bodhidharma, revered as the first Zen patriarch, is still beloved, and still portrayed with the look of a pirate, rough and nasty, bearded, scowling, with a hoop in one ear. The enlarged look of his eyes is due to the absence of lids, for supposedly, the inclination of eyelids to close when sleepy interfered with Bodhidharma’s resolute sitting meditation, and so he cut them off. Whether or not this story is factual, it remains an indication of the radical Zen school of awakened masters that emerged. Bodhidharma’s successor, Hui-k'o in Chinese, Eka in Japanese, cut off his own arm as a testament to how serious he was about awakening. Eka succeeds Bodhidharma to become the second Zen patriarch.

After only two successions, between severed eyelids and an amputated arm, the uncompromising style of this Buddhist school could already be characterized by Barry Goldwater's memorable, Extremism in the name of liberty is no vice.

The liberty of which Senator Goldwater spoke referred to the American principles of democratic rule, while extremism argued in favor of the hapless effort to defend democracy by opposing Communist forces in Vietnam. Bodhidharma’s concerns with liberation were neither political nor dualistic, yet in both cases extremism is associated with shedding blood and fierce warriorship. This extremism is hard-edged, wounding, stoic, and sacrificial. In Zen history, as in war, the esthetic has been defined by men; and the intense muscularity of Zen remained very much part of the tradition inherited by both men and women in the West.

Eighty generations of lineage holders in the Soto Zen line have been patriarchs. Lex Hixon, as a Dharma heir of the American teacher, Tetsugen Glassman, is in the eighty-second generation. Beginning with Glassman Sensei’s eighty-first generation, through the blessings of his teacher, Taizan Maezumi Roshi, women have been granted full teaching authority. The passing of the patriarchal era lies mercifully in sight. For those concerned with this issue, Living Buddha Zen proves to be an unexpected ally.

Living Buddha Zen excels at the difficult task of speaking of silence in a language that expresses the authentic Zen terrain while releasing the imagery from its masculine stronghold. Here, the whip-cracking exchanges of bare-boned Zen discourse convert into generous, aromatic prose; tough love is replaced with unabashed devotion; the confidence of the disciple softens the hierarchical authority of the master. Here, love for the teacher, love for the Buddha Dharma, and love for life itself is emotionally charged, passionate, sensual. Tales of Zen life on the razor's edge are retold in language that is pliable and poetic. Pick a paragraph at random, and you may hear Rumi, Milarepa, or the Song of Solomon, but not Zen — at least not the Zen to which we have grown accustomed. You may even hear the voice of a woman.

Translation for Hixon is a process of transformation, translating from the inside out, from the heart and from his own understanding. If he has circumvented certain rules of the game, his choices have not been arbitrary. With a Ph.D. in religion from Columbia and seven books in print, he has spent thirty years investigating the initiatory lineages of various sacred traditions. The modern, secular, skeptical, scientific view has not been casually jettisoned by Hixon, but shed slowly, through trial and error, personal inquiry, reliable spiritual guidance, and fearless commitment to a naked vision.

Living Buddha Zen is not just a contemporary rendering of an old text, nor a lyrical account of one man's Zen story. Rather, like the great Zen classics, it embodies Zen in the manner of Master Dogen as “the full moon way, complete from the very beginning.” Living Buddha Zen is not a manual for enlightenment, yet it contains the essentialized teachings of Zen.

With Zen practice centers flourishing all over North America and the modem world, Hixon's audience is vastly different from D.T. Suzuki’s. So he offers not just an introduction, but an invitation to receive initiation and to pursue face-to-face study with a master, as he himself has done. As well, this book is a compendium of warnings against subtle forms of avoidance and inflation which masquerade as spiritual practice and realization.

As a genuine lineage holder, Hixon writes with the full empowerment of successive generations of adepts. But his special genius is to become the flexible vehicle through which this prodigious spiritual energy flows, while steadying himself in its midst long enough for his heart to find its voice for our benefit. This is the vow of the bodhisattva, and it affirms Living Buddha Zen as an authentic continuation of the transmission of light.

WHAT IS THIS BOOK?

This book is a union of personal and planetary history. To begin within the personal dimension, in 1991, when the October full moon, the orange harvest moon, was setting at dawn, on the day the Dalai Lama offered the ancient Tantric Kalachakra initiation at Madison Square Garden, I drove to meet my Zen master, Bernard Tetsugen Glassman Sensei. He is a Brooklyn kid who migrated West to the aerospace industry in southern California, becoming spiritual successor in 1976 to Taizan Maezumi Roshi, a Japanese Zen master living in Los Angeles. In 1979, Sensei Glassman returned to New York City to take his Zen seat here. I encountered him immediately.

So it was as old friends that Sensei and I sat together in radiant silence that early autumn morning in 1991, and then engaged in easy conversation, exploring the enlightenment experience of Shakyamuni Buddha. The essence of this meeting, and our subsequent fifty-two meetings over three years, tracing the transmission of Shakyamuni's enlightenment down fifty-two generations, is now recorded by Living Buddha Zen.

The present pages were born from Sensei Glassman’s intuition that I should write a book about our mutual study of these koan, these dramas of spiritual transmission between living Buddhas and their destined successors — twenty-eight generations in India, twenty-two generations in China, two generations in Japan. Sensei’s understanding of my need to write — a need which, as essentially a non-writing person, he does not share — reminds me of anthropologist Carlos Castaneda and his Yaqui Indian guide, Don Juan. The Native American sage realized that his modern apprentice could not get the rational mind out of the way unless he wrote voluminous field-notes.

The timeless sage in the present case, Bernard Glassman, emerged from modern culture with a Ph.D. in mathematics and an instinctive sense of business organization as a vehicle for social and spiritual action. Glassman is a Jewish Zen master who has vowed to end homelessness in Yonkers, the depressed community where he lives just north of New York City. He began from the entrepreneurial base of a gourmet bakery, staffed at first by his Zen students and now by inner city persons who have come through the Greystone Bakery job training program. The Sensei presently receives state grants to fund his programs for housing single mothers, infant day care, and now a residential AlDs facility for the homeless. Glassman has also founded the House of One People, an inner city community center where members of all religions can come to worship, meditate, and celebrate, both together and separately, in an atmosphere of social renewal and spiritual harmony.

These and many other projects are all undertaken in the unitive spirit of Shakyamuni Buddha's enlightenment. Glassman's own resolution of some one thousand Zen koan prepared him to develop a social vision rooted in the Buddhist principle of nonduality. Even his Zen teaching program, How to Raise an Ox, integrates the practical wisdom of the twelve-step movement, originally inspired by Alcoholics Anonymous, into the traditional Buddhist understanding of the path to enlightenment. Twice a year, Sensei leads a seven-day Street Retreat, when he and a few Zen students wholeheartedly join the homeless population of New York City, living in shelters and eating at soup kitchens, to which they later give anonymous financial contributions.

Bernard Glassman is hardly the romantic figure from another world, or worlds, that we encounter in the sorcerer Don Juan. Yet when seated face to face with Sensei in silence, an ancient wisdom-being is clearly manifest — mysterious, belonging to all worlds and to no world, a great being inseparable from the fifty-three Awakened Ones we approach through the pages of Living Buddha Zen.

The original work at the base of Living Buddha Zen is the fourteenth-century Japanese masterpiece by Keizan Zeriji, Denkoroku: The Record of Transmitting the Light. This text purports to trace the transmission from master to successor of the enlightenment of Shakyamuni Buddha through one thousand seven hundred years to the world-teacher, Dogen Zenji, in thirteenth-century Japan. Master Dogen is considered the father of the Soto Zen Order, which has twenty-five thousand temples and ten million practitioners in contemporary Japan. His seminal work, Shobogenzo: The Treasure House of the Eye of True Dharma, has profoundly inspired both Eastern and Western philosophers and spiritual practitioners during this century, after remaining in obscurity, even in its native land, for some seven hundred years. Master Keizan is considered the mother of Soto Zen, his Denkoroku being the reservoir or womb of the lineage.

The Denkoroku is a fifty-three stroke ink and brush drawing of essential Buddhist history. Seen more broadly, this text presents in the direct Zen manner the essential nature of awareness, the single Light celebrated by all ancient wisdom traditions. The Denkoroku is a work of art whose subject is sacred history. It is not historiography.

Even more than a work of art, this text is a vehicle for mutual study between Zen masters and their successors, honing the insight of each and insuring the actual continuation, without diminution, of Dogen Zenjis radical spiritual teaching, perpetual plenitude — the perfect awakeness, here and now, of all beings and worlds. This transmission of Light remains continuous throughout the unpredictable developments of planetary history, such as the transplanting of Zen from Japan to America and, from America, to the strange global landscape called the postmodern world.

These are some reasons why Sensei Glassman chose the Denkoroku as the text for our mutual study, preparing me for the Dharma transmission in which I will be invested with responsibility for pouring Light into the next generation. The formal ceremonies are scheduled to be celebrated in Japan and New York during 1995.