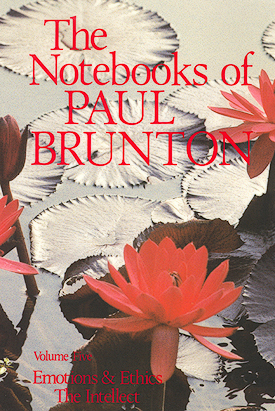

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton volume 5

Emotions and Ethics /

The Intellect By Paul Brunton

Retail/cover price: $18.95

Our price : $15.16

(You save $3.79!)

About this book:

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton volume 5

Emotions and Ethics /

The Intellect

by Paul Brunton

"The question is . . . to accept the baser weaknesses as human or . . . to struggle against them as unworthy of a human being." —Paul Brunton

Subjects: Philosophy, Spirituality, Ethics

5.75 x 8.5, softcover

(hardcover is available)

432 pages

ISBN 10: 0-943914-22-1

ISBN 13: 978-0-943914-22-0

Book Details

One of Paul Brunton's truly significant contributions, this volume offers a mature spiritual perspective on the importance of character development, personality refinement, and proper use of the thinking faculty.

Part 1, Emotions and Ethics, explores two fundamental relationships. The first is that between character development and spiritual progress; the second is that between personality refinement and spiritual self-expression.

Part 2, The Intellect, explains the important role, and the limitations, of the thinking faculty as a transformative potency in spiritual practice.

Category Six: EMOTIONS AND ETHICS

INTRODUCTION

1. UPLIFT CHARACTER

Environmental influence

Moral relativity

Conscience

Goodness

Altruism

Patience, perseverance

Value of confession, repentance

Truthfulness

2. RE-EDUCATE FEELINGS

Love, compassion

Detachment

Family

Friendship

Marriage

Happiness

3. DISCIPLINE EMOTIONS

Higher and lower emotions

Self-restraint

Matured emotion

4. PURIFY PASSIONS

5. SPIRITUAL REFINEMENT

Courtesy, tolerance, considerateness

Spiritual value of manners

Discipline of speech

Accepting criticism

Refraining from criticism

Forgiveness

Criticizing constructively

Sympathetic understanding

6. AVOID FANATICISM

7. MISCELLANEOUS ETHICAL ISSUES

Nonviolence, nonresistance, pacifism

Category Seven: THE INTELLECT

INTRODUCTION

1. THE PLACE OF INTELLECT

Its value

Its limitations

Its inward vision

Reason, intuition, and insight

2. THE SERVICE OF INTELLECT

Cultivation of intelligence

Balance of intellect and feeling

Doubt and the modern mind

3. THE DEVELOPMENT OF INTELLECT

Independence and individuality

Comparison and synthesis

Authority and the past

Books

4. ABSTRACT THOUGHT

Facts and logic

The need for precision

5. SEMANTICS

Clarity is essential

The problem with words

The meaning of language

6. SCIENCE

Influence of science

When science stands alone

Science and metaphysics

7. METAPHYSICS OF TRUTH

Speculation vs. knowledge

Issues and adherents

Its spiritual significance

8. INTELLECT, REALITY, AND THE OVERSELF

“. . . a veritable treasure-trove of philosophic-spiritual wisdom.” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

“. . . sensible and compelling. His work can stand beside that of such East-West bridges as Merton, Huxley, Suzuki, Watts, and Radhakrishnan. It should appeal to anyone concerned personally and academically with issues of spirituality.” —Choice

“Vigorous, clear-minded and independent . . . a synthesis of Eastern mysticism and Western rationality. . . A rich volume.” —Library Journal

“. . . a great gift to us Westerners who are seeking the spiritual.” —Charles T. Tart

“A person of rare intelligence. . . thoroughly alive, and whole in the most significant, 'holy' sense of the word.” —Yoga Journal

For more reviews of the Notebooks series, click here

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category six, Emotions and Ethics

Emotions and Ethics deals with two direct relationships not often adequately recognized. The first is that between character development and spiritual awakening. The second is that between personality refinement and spiritual self-expression. The evolutionary process of recognizing and developing these relationships traces a course through the animal, human, and angelic possibilities within our own individual souls.

You will know only so much of the Divine, this section seems to say, as you yourself can become. You will see its actions in your own life to the extent that you master your own baser nature and cultivate your own latent spiritual nobility. You will see its benign presence in the world around you to the extent that you first, see the working of evolutionary laws in human experience and, second, consciously place your own maturing intelligence into the service of that evolutionary development. Purification of motive and act must precede reliable revelation.

Within our hearts, this section says—under the agitations, doubts, and desires—is a reliable source of individualized ethical guidance for daily living. We can know what is best in a given situation and we can respond creatively and positively to its needs by drawing upon spiritual resources from within. But to make use of this guidance, we must first acquire enough self-discipline to discern its voice among the many that contend within us. And we must acquire enough strength of will to act as it would have us do. Only in doing this do we truly become it. And only in ourselves becoming it do we come to the calm, unshakeable certitude that it is.

Editorial policy with regard to selection and placement of the material in this section is the same as that mentioned in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that the para also appears in Perspectives, the survey volume to this series.

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category seven, The Intellect

In light of the material in Emotions and Ethics, category seven, The Intellect, takes on deeper meaning and significance. Emotions and Ethics tells us that our passions, emotions, and feelings must come to be guided by reason, and that reason itself must be guided by intuition. The Intellect helps us to understand what reason and intuition are, and how they contribute to the individual intelligence that is born out of their creative union.

This section quickly establishes three major points. First, intelligence is to be honored and developed as one of the divine qualities potential in human character. Second, speculative intellection, unguided by wisdom, is of little or no use in spiritual matters; this is as true of what this kind of blind intellection asserts about the Divine as of what it critically denies. Third, the matured and properly trained intelligence not only makes it easier for us to know when to think and when to suspend thinking; it also becomes a powerful tool for precise communication of higher intuitions and mystical perceptions. In its most developed form, this intelligence can formulate what P.B calls a "metaphysics of truth": an inspired, fluid structure of revelatory reasoning whereby the Proficient can express, in intellectual terms, much of what has been learned through intellect-transcending inner vision and direct experience.

Editorial policy with regard to selection and placement of the material in this section is the same as that mentioned in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that the para also appears in Perspectives, the survey volume to this series.

Excerpts from Notebooks category six: Emotions and Ethics

Prefatory:

Is there no basis of morality and taste, no standard of judgement and ethics, except that which the individual brings with himself or creates for himself? The situation is not so anarchic as it seems, for there is a progressive evolutionary character running through all these different points of view.

The human journey from mere animal existence to real spiritual essence is reflected in human ethics, where rules imposed from without are gradually supplanted by principles intuited from within.

From chapter 1: UPLIFT CHARACTER

1

If we will bring more sincerity and more integrity into our lives, more truth and more wisdom into our minds, more goodwill and more self-discipline into our hearts, not only will we be more blessed but also all others with whom we are in touch.

2

Face yourself if you would find yourself. By this I do not only mean that you are to seek out and study the pathetic weaknesses of your lower nature, but also the noble inspirations of your higher nature.

3

Philosophy guides human conduct not so much by imposing a particular code of rules to be obeyed as by inculcating a general attitude to be developed. It does not tell us what to do so much as it helps us to get the kind of spiritual knowledge and moral perception which will tell us what to do.

4

The moral precepts which it offers for use in living and for guidance in wise action are not offered to all alike, but only to those engaged on the quest. They are not likely to appeal to anyone who is virtuous merely because he fears the punishment of sin rather than because he loves virtue itself. Nor are they likely to appeal to anyone who does not know where his true self-interest lies. There would be nothing wrong in being utterly selfish if only we fully understood the self whose interest we desire to preserve or promote. For then we would not mistake pleasure for happiness nor confuse evil with good. Then we would see that earthly self-restraint in some directions is in reality holy self-affirmation in others, and that the hidden part of self is the best part.(P)

5

These ideals have been reiterated too often to be new, but concrete application of them to the actual state of affairs would be new.

6

This grand section of the quest deals with the right conduct of life. It seeks both the moral re-education of the individual's character for his own benefit and the altruistic transformation of it for society's benefit.(P)

7

We have free will to change our character, but we must also call upon God's assistance. We are likely to fail without it and it is possible by striving too earnestly all alone to make ourselves mentally or physically ill. We should Pray and ask for God's help even when trying to make ourselves have faith in a Higher Power as well as in ourselves.

8

We begin and end the study of philosophy by a consideration of the subject of ethics. Without a certain ethical discipline to start with, the mind will distort truth to suit its own fancies. Without a mastery of the whole course of philosophy to its very end, the problem of the significance of good and evil cannot be solved.(P)

9

The foundation of this work is a fine character. He who is without such moral development will be without personal control of the powers of the mind when they appear as a result of this training; instead those powers will be under the control of his ego. Sooner or later he will injure himself or harm others. The philosophic discipline acts as a safeguard against these dangers.

10

All those points of metaphysical doctrine and religious history like the problem of evil and the biography of avatars are doubtful, if not insoluble, whereas all the points of moral attitude and personal conduct like honesty, justice, goodness, and self-control are both indisputable and essential. Here we walk on trustworthy ground. Why not then leave others to quarrel fiercely about the first and let us abide peacefully in the second.

From chapter 2: RE-EDUCATE FEELINGS

1

The proper cultivation and refinement of feeling is necessary for the philosophic path, but this must not be confused with mere emotionalism. The former lifts him to higher and higher levels while the latter keeps him pinned down to egoism. The former gives him the right kind of inner experience, but the latter often deceives him.

2

It is right to rule the passions and lower emotions by reasoned thinking, but reason itself must be companioned by the higher and nobler emotions or it will be unbalanced.

3

As man's impulses to action come mainly from his feelings, hence it is necessary to re-educate his feelings if we would get him to act aright.

4

There are three kinds of feeling. The lowest is passional. The highest is intuitional. Between them lies the emotional.

5

It is not emotion in itself that philosophy asks us to triumph over but the lower emotions. On the contrary, it asks us to cherish and cultivate the higher ones. It is not feeling in itself that is to be ruled sternly by reason but the blind animal instincts and ignorant human self-seeking. When feeling is purified and disciplined, exalted and ennobled, depersonalized and instructed, it becomes the genuine expression of philosophical living.

6

The heart must also acknowledge the truth of these sacred tenets, for then only can the will apply it in common everyday living.

7

Those are much mistaken who think the philosophic life is one of dark negation and dull privation, of sour life-denial and emotional refrigeration. Rather is it the happy cultivation of Life's finest feelings.

8

The hardest thing in the emotional life of the aspirant is to tear himself away from his own past. Yet in his capacity to do this lies his capacity to gain newer and fresher ideals, motives, habits, and powers. Through this effort he may find new patterns for living and re-educate himself psychologically.

9

But it is not all his ideas which govern man's life. Only those are decisive which are breathed and animated by his feelings, only they prompt him to action. Hence a merely intellectualist acceptance of these teachings, although good, does not suffice alone.

10

The aspirant needs to rise above his emotional self, without rising above the capacity to feel, and to govern it by reason, will, and intuition.

Excerpts from Notebooks category seven: The Intellect

Prefatory:

It is inborn in the human mind to wish to know. If this begins with the endless surface questions of a child's curiosity, if it continues into the deeper questions of a scientist's probing investigation, it cannot and does not stop there. For the higher part of the mind will eventually come into unfoldment, that union of abstract reflective thought with mystical intuition which is true intelligence, which needs and sees a view of the whole of things. And so the knowing faculty enters the realm of philosophy.

From chapter 1: THE PLACE OF INTELLECT

1

Let us honour intelligence, and not insult it, for it is as much from God as piety.

2

The intellect cannot lead us to infallible truth, yes, but it can keep us from straying into roads that would lead us to utter falsehood.

3

What was called "Reason" in The Hidden Teaching Beyond Yoga and what was honoured as "Reason" by the Cambridge Platonists is a mystical plus intellectual faculty and not merely an intellectual one. It is not merely a coexistence but a fusion of the two capacities.

4

If we reverse the words of Descartes, whose thought helped usher in the age of science, and proclaim, "I am, therefore I think" we come nearer to the truth.

5

True intelligence is the working union of three active faculties: concrete thinking, abstract thinking, and mystical intuition.

6

The intellect can only speak for the Overself after the Glimpse has vanished and turned to a mere memory. That is to say, it is really speaking for itself, for what it thinks about the Overself. It has no really valid authority to speak.

7

The wisdom of God cannot be found by the intellect of man.

8

The fragment of knowledge which the finite mind can absorb and hold is so little that we must remain humble always.

9

He may recognize the truth with his intellect and yet be unable to realize it with his consciousness.

10

The intellect ought to work only as a servant, obeying intuitions orders in practical life or filling in details for intuition's discoveries in the truth-seeking quest.

11

These competing tendencies of intuition and reason may, however, be harmonized in a balanced personality. All mystics have not advocated the paralysis of intellect - even Jacob Boehme wrote: "Human reason, by being kept within its true bounds and regulated by a superior light, is only made useful. Both the divine and natural life may in the soul subsist together and be of mutual service each to the other."

From chapter 3: THE DEVELOPMENT OF INTELLECT

1

When intelligence is applied so thoroughly as to yield a whole view and not merely a partial view of existence, when it is applied so persistently as to yield a steady insight into things rather than a sporadic one, when it is applied so detachedly as to be without regard to personal preconceptions, and when it is applied so calmly that feelings and passions cannot alter its direction, then and only then, does a man become truly reasonable and capable of intellectually ascertaining truth.(P)

2

We must think before we can understand the soul's existence; we must understand before we can realize it.

3

The earliest beginnings of thought, as apart from instinct, when it was itself still but a lurking tendency, belong far back in primeval time. The human intellect as we find it today, so rich and developed an instrument for the consciousness of the ego, did not arrive at this fullness without a series of graduated stages.

4

We have had plenty of scientific thinking, business thinking, and political thinking long enough, but we have had very little inspired thinking. That is the world's need.

5

The intellect is cradled in selfishness but runs the evolutionary track into reason where it will one day finish at the winning-post of selflessness.

6

The animal acts as its instinctive drives bid it act whereas in man this instinctive nature is made up with and consequently modified by, the awakening intellect's need to consider, compare, and judge.

7

He who wants to go back to the simple medieval life is welcome to it. He who wants his rooms cleaned with old-fashioned brooms that raise a cloud of dust and leave it hanging in the air until it can find safe lodgement in throats and lungs, is welcome to the dust. There are others, however, who react differently to such a situation; who are resolved to take advantage of the skill of human brains and the fact of human advance. They have thrown away the unhealthy broom and adopted the vacuum cleaner which removes and swallows the dust instead of filling the air with it. We are not writing a thesis on domestic hygiene. We are writing in this strain because it is highly symbolic. It shows quite vividly the difference between the backward looking mentality and the forward looking one. The student of philosophy belongs to the second category. He sees the futility of propagating a switch-back to medieval methods when we are in the midst of the greatest technical transformation mankind has ever known. He knows that modern conditions must be faced with modern attitudes. However, he takes "modern" to mean whatever has attained the most finished state as a consequence of progressive development. He knows it does not mean whatever is merely fashionable at the moment, as materialism was fashionable in intellectual circles and sensualism in youthful circles until very lately. His vision is larger than that of his contemporaries, because it encompasses more. They are modern only in a chronological sense, but backward in a spiritual one.

8

It is the faculty of reason which differentiates human beings from all Nature's other creatures. It is this which sets man beyond the animals. But reason untouched by the finer promptings of the heart, and unillumined by the sublimer intuitions of the mind, degenerates easily into selfish cunning, and degrades instead of dignifying man.

9

It may be they find it too hard to make the crossing from the older way of thinking to what is demanded of them by the new knowledge: a willingness to accept paradox. For otherwise they get only a half-truth.

10

Reason gradually becomes paramount as man develops through life after life.

In his own words:

“Writing, which is an exercise of the intellect to some, is an act of worship to me. I rise from my desk in the same mood as that in which I leave an hour of prayer in an old cathedral, or of meditation in a little wood . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 143

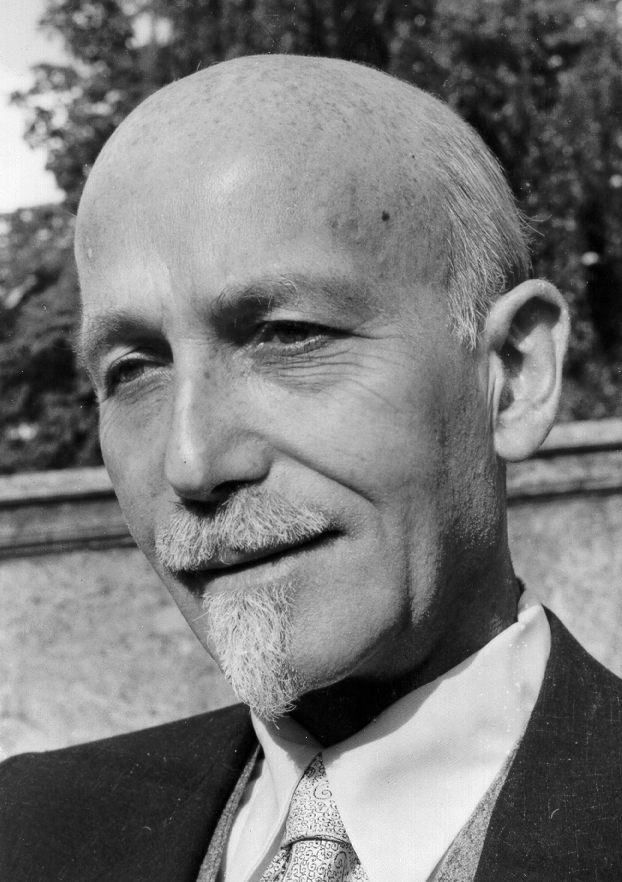

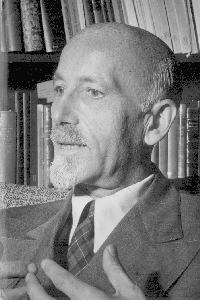

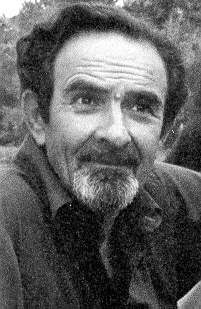

“P.B. as a private person does not count. There are hundreds of millions of such persons anyway. What is one man and his quest? P.B.’s personal experiences and views are not of any particular importance or special consequence. What happens to the individual man named P.B. is a matter of no account to anyone except himself. But what happens to the hundreds of thousands of spiritual seekers today who are following the same path that he pioneered is a serious matter and calls for prolonged consideration. Surely the hundreds of thousands of Western seekers who stand behind him and whom indeed, in one sense, he represents, do count. P.B. as a symbol of the scattered group of Western truth-seekers who, by following his writings so increasingly and so eagerly, virtually follow him also, does count. He personifies their aspirations, their repulsion from materialism and attraction toward mysticism, their interest in Oriental wisdom and their shepherdless state. As a symbol of this Western movement of thought, he is vastly greater than himself. In his mind and person the historic need for a new grasp of the contemporary spiritual problem found a plain-speaking voice . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 145

Learn more about Paul Brunton through articles at the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation web site

Electronic versions of this book are available from all major (Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, etc.) and most smaller ebook vendors. Please don't try to order ebooks directly from us, as we are not yet able to deliver anything to you in a preferred electronic format.

To see all our Paul Brunton titles, scroll down to The Complete Paul Brunton Opus below.

To see and/or order individual volumes in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, hover your mouse over the specific cover in the Notebooks section of Complete Paul Brunton Opus below, then click on Details in the box that appears within it.

Click here to see or order the complete set of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

Paul Brunton helps us hear the melody behind the medley of today's "spiritual marketplace." His late writings raise the bar for what we can expect of spiritual teachings and teachers, and what we can do for ourselves. Born in London in 1898, he soon became a leading pioneer of much of what we now take for granted. He traveled widely throughout the world (long before it was fashionable) to meet living masters of various traditions with whom he then lived and studied. His eleven early books from 1934–1952 shared much of what he learned, and helped set the stage for dramatic east-west exchanges of the late 20th century. Paul Brunton left more than 10,000 pages of enormously helpful new work in notebooks he reserved for posthumous publication, much of which is now available as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. See "The Complete Paul Brunton Opus" in blue below to see his many works available on this site. You can also search on Paul Brunton in the search bar to browse the selections, or click on a link below for specific connections.

Click here for an article about Paul Brunton.

Click here for The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

To access small theme-based books compiled from Paul Brunton's writings, scroll down to Derived from the Notebooks below.

To access Paul Brunton's early writings, published from 1934–1952, scroll down to Paul Brunton's Early Works below.

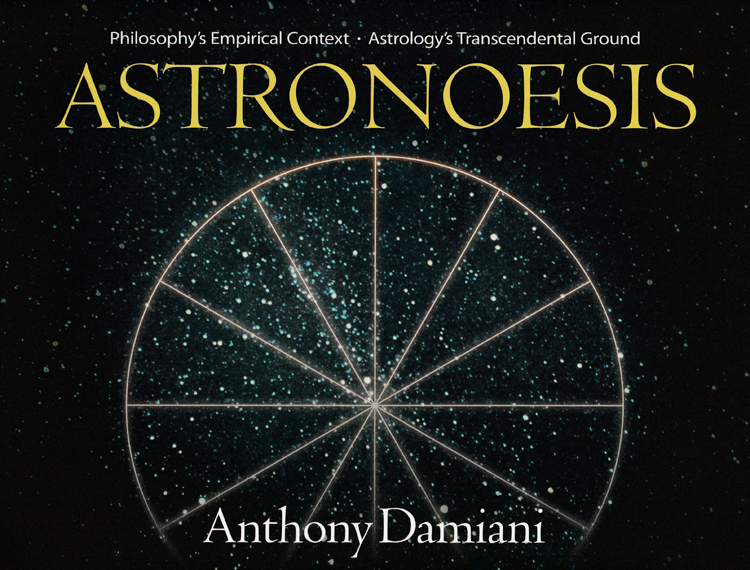

To access commentaries on Paul Brunton and his work by his leading student, Anthony Damiani, as well as other writings about Paul Brunton and/or his work, scroll down to Commentaries and Reflections on Paul Brunton and His Work below.

Book Details

One of Paul Brunton's truly significant contributions, this volume offers a mature spiritual perspective on the importance of character development, personality refinement, and proper use of the thinking faculty.

Part 1, Emotions and Ethics, explores two fundamental relationships. The first is that between character development and spiritual progress; the second is that between personality refinement and spiritual self-expression.

Part 2, The Intellect, explains the important role, and the limitations, of the thinking faculty as a transformative potency in spiritual practice.

Category Six: EMOTIONS AND ETHICS

INTRODUCTION

1. UPLIFT CHARACTER

Environmental influence

Moral relativity

Conscience

Goodness

Altruism

Patience, perseverance

Value of confession, repentance

Truthfulness

2. RE-EDUCATE FEELINGS

Love, compassion

Detachment

Family

Friendship

Marriage

Happiness

3. DISCIPLINE EMOTIONS

Higher and lower emotions

Self-restraint

Matured emotion

4. PURIFY PASSIONS

5. SPIRITUAL REFINEMENT

Courtesy, tolerance, considerateness

Spiritual value of manners

Discipline of speech

Accepting criticism

Refraining from criticism

Forgiveness

Criticizing constructively

Sympathetic understanding

6. AVOID FANATICISM

7. MISCELLANEOUS ETHICAL ISSUES

Nonviolence, nonresistance, pacifism

Category Seven: THE INTELLECT

INTRODUCTION

1. THE PLACE OF INTELLECT

Its value

Its limitations

Its inward vision

Reason, intuition, and insight

2. THE SERVICE OF INTELLECT

Cultivation of intelligence

Balance of intellect and feeling

Doubt and the modern mind

3. THE DEVELOPMENT OF INTELLECT

Independence and individuality

Comparison and synthesis

Authority and the past

Books

4. ABSTRACT THOUGHT

Facts and logic

The need for precision

5. SEMANTICS

Clarity is essential

The problem with words

The meaning of language

6. SCIENCE

Influence of science

When science stands alone

Science and metaphysics

7. METAPHYSICS OF TRUTH

Speculation vs. knowledge

Issues and adherents

Its spiritual significance

8. INTELLECT, REALITY, AND THE OVERSELF

“. . . a veritable treasure-trove of philosophic-spiritual wisdom.” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

“. . . sensible and compelling. His work can stand beside that of such East-West bridges as Merton, Huxley, Suzuki, Watts, and Radhakrishnan. It should appeal to anyone concerned personally and academically with issues of spirituality.” —Choice

“Vigorous, clear-minded and independent . . . a synthesis of Eastern mysticism and Western rationality. . . A rich volume.” —Library Journal

“. . . a great gift to us Westerners who are seeking the spiritual.” —Charles T. Tart

“A person of rare intelligence. . . thoroughly alive, and whole in the most significant, 'holy' sense of the word.” —Yoga Journal

For more reviews of the Notebooks series, click here

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category six, Emotions and Ethics

Emotions and Ethics deals with two direct relationships not often adequately recognized. The first is that between character development and spiritual awakening. The second is that between personality refinement and spiritual self-expression. The evolutionary process of recognizing and developing these relationships traces a course through the animal, human, and angelic possibilities within our own individual souls.

You will know only so much of the Divine, this section seems to say, as you yourself can become. You will see its actions in your own life to the extent that you master your own baser nature and cultivate your own latent spiritual nobility. You will see its benign presence in the world around you to the extent that you first, see the working of evolutionary laws in human experience and, second, consciously place your own maturing intelligence into the service of that evolutionary development. Purification of motive and act must precede reliable revelation.

Within our hearts, this section says—under the agitations, doubts, and desires—is a reliable source of individualized ethical guidance for daily living. We can know what is best in a given situation and we can respond creatively and positively to its needs by drawing upon spiritual resources from within. But to make use of this guidance, we must first acquire enough self-discipline to discern its voice among the many that contend within us. And we must acquire enough strength of will to act as it would have us do. Only in doing this do we truly become it. And only in ourselves becoming it do we come to the calm, unshakeable certitude that it is.

Editorial policy with regard to selection and placement of the material in this section is the same as that mentioned in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that the para also appears in Perspectives, the survey volume to this series.

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category seven, The Intellect

In light of the material in Emotions and Ethics, category seven, The Intellect, takes on deeper meaning and significance. Emotions and Ethics tells us that our passions, emotions, and feelings must come to be guided by reason, and that reason itself must be guided by intuition. The Intellect helps us to understand what reason and intuition are, and how they contribute to the individual intelligence that is born out of their creative union.

This section quickly establishes three major points. First, intelligence is to be honored and developed as one of the divine qualities potential in human character. Second, speculative intellection, unguided by wisdom, is of little or no use in spiritual matters; this is as true of what this kind of blind intellection asserts about the Divine as of what it critically denies. Third, the matured and properly trained intelligence not only makes it easier for us to know when to think and when to suspend thinking; it also becomes a powerful tool for precise communication of higher intuitions and mystical perceptions. In its most developed form, this intelligence can formulate what P.B calls a "metaphysics of truth": an inspired, fluid structure of revelatory reasoning whereby the Proficient can express, in intellectual terms, much of what has been learned through intellect-transcending inner vision and direct experience.

Editorial policy with regard to selection and placement of the material in this section is the same as that mentioned in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that the para also appears in Perspectives, the survey volume to this series.

Excerpts from Notebooks category six: Emotions and Ethics

Prefatory:

Is there no basis of morality and taste, no standard of judgement and ethics, except that which the individual brings with himself or creates for himself? The situation is not so anarchic as it seems, for there is a progressive evolutionary character running through all these different points of view.

The human journey from mere animal existence to real spiritual essence is reflected in human ethics, where rules imposed from without are gradually supplanted by principles intuited from within.

From chapter 1: UPLIFT CHARACTER

1

If we will bring more sincerity and more integrity into our lives, more truth and more wisdom into our minds, more goodwill and more self-discipline into our hearts, not only will we be more blessed but also all others with whom we are in touch.

2

Face yourself if you would find yourself. By this I do not only mean that you are to seek out and study the pathetic weaknesses of your lower nature, but also the noble inspirations of your higher nature.

3

Philosophy guides human conduct not so much by imposing a particular code of rules to be obeyed as by inculcating a general attitude to be developed. It does not tell us what to do so much as it helps us to get the kind of spiritual knowledge and moral perception which will tell us what to do.

4

The moral precepts which it offers for use in living and for guidance in wise action are not offered to all alike, but only to those engaged on the quest. They are not likely to appeal to anyone who is virtuous merely because he fears the punishment of sin rather than because he loves virtue itself. Nor are they likely to appeal to anyone who does not know where his true self-interest lies. There would be nothing wrong in being utterly selfish if only we fully understood the self whose interest we desire to preserve or promote. For then we would not mistake pleasure for happiness nor confuse evil with good. Then we would see that earthly self-restraint in some directions is in reality holy self-affirmation in others, and that the hidden part of self is the best part.(P)

5

These ideals have been reiterated too often to be new, but concrete application of them to the actual state of affairs would be new.

6

This grand section of the quest deals with the right conduct of life. It seeks both the moral re-education of the individual's character for his own benefit and the altruistic transformation of it for society's benefit.(P)

7

We have free will to change our character, but we must also call upon God's assistance. We are likely to fail without it and it is possible by striving too earnestly all alone to make ourselves mentally or physically ill. We should Pray and ask for God's help even when trying to make ourselves have faith in a Higher Power as well as in ourselves.

8

We begin and end the study of philosophy by a consideration of the subject of ethics. Without a certain ethical discipline to start with, the mind will distort truth to suit its own fancies. Without a mastery of the whole course of philosophy to its very end, the problem of the significance of good and evil cannot be solved.(P)

9

The foundation of this work is a fine character. He who is without such moral development will be without personal control of the powers of the mind when they appear as a result of this training; instead those powers will be under the control of his ego. Sooner or later he will injure himself or harm others. The philosophic discipline acts as a safeguard against these dangers.

10

All those points of metaphysical doctrine and religious history like the problem of evil and the biography of avatars are doubtful, if not insoluble, whereas all the points of moral attitude and personal conduct like honesty, justice, goodness, and self-control are both indisputable and essential. Here we walk on trustworthy ground. Why not then leave others to quarrel fiercely about the first and let us abide peacefully in the second.

From chapter 2: RE-EDUCATE FEELINGS

1

The proper cultivation and refinement of feeling is necessary for the philosophic path, but this must not be confused with mere emotionalism. The former lifts him to higher and higher levels while the latter keeps him pinned down to egoism. The former gives him the right kind of inner experience, but the latter often deceives him.

2

It is right to rule the passions and lower emotions by reasoned thinking, but reason itself must be companioned by the higher and nobler emotions or it will be unbalanced.

3

As man's impulses to action come mainly from his feelings, hence it is necessary to re-educate his feelings if we would get him to act aright.

4

There are three kinds of feeling. The lowest is passional. The highest is intuitional. Between them lies the emotional.

5

It is not emotion in itself that philosophy asks us to triumph over but the lower emotions. On the contrary, it asks us to cherish and cultivate the higher ones. It is not feeling in itself that is to be ruled sternly by reason but the blind animal instincts and ignorant human self-seeking. When feeling is purified and disciplined, exalted and ennobled, depersonalized and instructed, it becomes the genuine expression of philosophical living.

6

The heart must also acknowledge the truth of these sacred tenets, for then only can the will apply it in common everyday living.

7

Those are much mistaken who think the philosophic life is one of dark negation and dull privation, of sour life-denial and emotional refrigeration. Rather is it the happy cultivation of Life's finest feelings.

8

The hardest thing in the emotional life of the aspirant is to tear himself away from his own past. Yet in his capacity to do this lies his capacity to gain newer and fresher ideals, motives, habits, and powers. Through this effort he may find new patterns for living and re-educate himself psychologically.

9

But it is not all his ideas which govern man's life. Only those are decisive which are breathed and animated by his feelings, only they prompt him to action. Hence a merely intellectualist acceptance of these teachings, although good, does not suffice alone.

10

The aspirant needs to rise above his emotional self, without rising above the capacity to feel, and to govern it by reason, will, and intuition.

Excerpts from Notebooks category seven: The Intellect

Prefatory:

It is inborn in the human mind to wish to know. If this begins with the endless surface questions of a child's curiosity, if it continues into the deeper questions of a scientist's probing investigation, it cannot and does not stop there. For the higher part of the mind will eventually come into unfoldment, that union of abstract reflective thought with mystical intuition which is true intelligence, which needs and sees a view of the whole of things. And so the knowing faculty enters the realm of philosophy.

From chapter 1: THE PLACE OF INTELLECT

1

Let us honour intelligence, and not insult it, for it is as much from God as piety.

2

The intellect cannot lead us to infallible truth, yes, but it can keep us from straying into roads that would lead us to utter falsehood.

3

What was called "Reason" in The Hidden Teaching Beyond Yoga and what was honoured as "Reason" by the Cambridge Platonists is a mystical plus intellectual faculty and not merely an intellectual one. It is not merely a coexistence but a fusion of the two capacities.

4

If we reverse the words of Descartes, whose thought helped usher in the age of science, and proclaim, "I am, therefore I think" we come nearer to the truth.

5

True intelligence is the working union of three active faculties: concrete thinking, abstract thinking, and mystical intuition.

6

The intellect can only speak for the Overself after the Glimpse has vanished and turned to a mere memory. That is to say, it is really speaking for itself, for what it thinks about the Overself. It has no really valid authority to speak.

7

The wisdom of God cannot be found by the intellect of man.

8

The fragment of knowledge which the finite mind can absorb and hold is so little that we must remain humble always.

9

He may recognize the truth with his intellect and yet be unable to realize it with his consciousness.

10

The intellect ought to work only as a servant, obeying intuitions orders in practical life or filling in details for intuition's discoveries in the truth-seeking quest.

11

These competing tendencies of intuition and reason may, however, be harmonized in a balanced personality. All mystics have not advocated the paralysis of intellect - even Jacob Boehme wrote: "Human reason, by being kept within its true bounds and regulated by a superior light, is only made useful. Both the divine and natural life may in the soul subsist together and be of mutual service each to the other."

From chapter 3: THE DEVELOPMENT OF INTELLECT

1

When intelligence is applied so thoroughly as to yield a whole view and not merely a partial view of existence, when it is applied so persistently as to yield a steady insight into things rather than a sporadic one, when it is applied so detachedly as to be without regard to personal preconceptions, and when it is applied so calmly that feelings and passions cannot alter its direction, then and only then, does a man become truly reasonable and capable of intellectually ascertaining truth.(P)

2

We must think before we can understand the soul's existence; we must understand before we can realize it.

3

The earliest beginnings of thought, as apart from instinct, when it was itself still but a lurking tendency, belong far back in primeval time. The human intellect as we find it today, so rich and developed an instrument for the consciousness of the ego, did not arrive at this fullness without a series of graduated stages.

4

We have had plenty of scientific thinking, business thinking, and political thinking long enough, but we have had very little inspired thinking. That is the world's need.

5

The intellect is cradled in selfishness but runs the evolutionary track into reason where it will one day finish at the winning-post of selflessness.

6

The animal acts as its instinctive drives bid it act whereas in man this instinctive nature is made up with and consequently modified by, the awakening intellect's need to consider, compare, and judge.

7

He who wants to go back to the simple medieval life is welcome to it. He who wants his rooms cleaned with old-fashioned brooms that raise a cloud of dust and leave it hanging in the air until it can find safe lodgement in throats and lungs, is welcome to the dust. There are others, however, who react differently to such a situation; who are resolved to take advantage of the skill of human brains and the fact of human advance. They have thrown away the unhealthy broom and adopted the vacuum cleaner which removes and swallows the dust instead of filling the air with it. We are not writing a thesis on domestic hygiene. We are writing in this strain because it is highly symbolic. It shows quite vividly the difference between the backward looking mentality and the forward looking one. The student of philosophy belongs to the second category. He sees the futility of propagating a switch-back to medieval methods when we are in the midst of the greatest technical transformation mankind has ever known. He knows that modern conditions must be faced with modern attitudes. However, he takes "modern" to mean whatever has attained the most finished state as a consequence of progressive development. He knows it does not mean whatever is merely fashionable at the moment, as materialism was fashionable in intellectual circles and sensualism in youthful circles until very lately. His vision is larger than that of his contemporaries, because it encompasses more. They are modern only in a chronological sense, but backward in a spiritual one.

8

It is the faculty of reason which differentiates human beings from all Nature's other creatures. It is this which sets man beyond the animals. But reason untouched by the finer promptings of the heart, and unillumined by the sublimer intuitions of the mind, degenerates easily into selfish cunning, and degrades instead of dignifying man.

9

It may be they find it too hard to make the crossing from the older way of thinking to what is demanded of them by the new knowledge: a willingness to accept paradox. For otherwise they get only a half-truth.

10

Reason gradually becomes paramount as man develops through life after life.

In his own words:

“Writing, which is an exercise of the intellect to some, is an act of worship to me. I rise from my desk in the same mood as that in which I leave an hour of prayer in an old cathedral, or of meditation in a little wood . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 143

“P.B. as a private person does not count. There are hundreds of millions of such persons anyway. What is one man and his quest? P.B.’s personal experiences and views are not of any particular importance or special consequence. What happens to the individual man named P.B. is a matter of no account to anyone except himself. But what happens to the hundreds of thousands of spiritual seekers today who are following the same path that he pioneered is a serious matter and calls for prolonged consideration. Surely the hundreds of thousands of Western seekers who stand behind him and whom indeed, in one sense, he represents, do count. P.B. as a symbol of the scattered group of Western truth-seekers who, by following his writings so increasingly and so eagerly, virtually follow him also, does count. He personifies their aspirations, their repulsion from materialism and attraction toward mysticism, their interest in Oriental wisdom and their shepherdless state. As a symbol of this Western movement of thought, he is vastly greater than himself. In his mind and person the historic need for a new grasp of the contemporary spiritual problem found a plain-speaking voice . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 145

Learn more about Paul Brunton through articles at the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation web site

Electronic versions of this book are available from all major (Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, etc.) and most smaller ebook vendors. Please don't try to order ebooks directly from us, as we are not yet able to deliver anything to you in a preferred electronic format.

To see all our Paul Brunton titles, scroll down to The Complete Paul Brunton Opus below.

To see and/or order individual volumes in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, hover your mouse over the specific cover in the Notebooks section of Complete Paul Brunton Opus below, then click on Details in the box that appears within it.

Click here to see or order the complete set of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

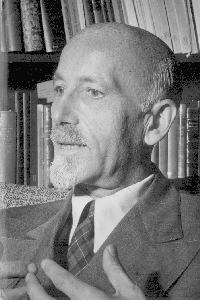

About Paul Brunton

Paul Brunton helps us hear the melody behind the medley of today's "spiritual marketplace." His late writings raise the bar for what we can expect of spiritual teachings and teachers, and what we can do for ourselves. Born in London in 1898, he soon became a leading pioneer of much of what we now take for granted. He traveled widely throughout the world (long before it was fashionable) to meet living masters of various traditions with whom he then lived and studied. His eleven early books from 1934–1952 shared much of what he learned, and helped set the stage for dramatic east-west exchanges of the late 20th century. Paul Brunton left more than 10,000 pages of enormously helpful new work in notebooks he reserved for posthumous publication, much of which is now available as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. See "The Complete Paul Brunton Opus" in blue below to see his many works available on this site. You can also search on Paul Brunton in the search bar to browse the selections, or click on a link below for specific connections.

Click here for an article about Paul Brunton.

Click here for The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

To access small theme-based books compiled from Paul Brunton's writings, scroll down to Derived from the Notebooks below.

To access Paul Brunton's early writings, published from 1934–1952, scroll down to Paul Brunton's Early Works below.

To access commentaries on Paul Brunton and his work by his leading student, Anthony Damiani, as well as other writings about Paul Brunton and/or his work, scroll down to Commentaries and Reflections on Paul Brunton and His Work below.

The Complete Paul Brunton Opus:

Paul Brunton's most mature work, in the order he specified for posthumous publication.

Smaller books on popular/timely themes, developed from the Notebooks and published posthumously.

Paul Brunton's works published during his lifetime from 1934-1952

Commentaries/Reflections by other authors on Paul Brunton or his works.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)