The Notebooks of Paul Brunton volume 10

The Orient: Its Legacy to the West By Paul Brunton

Retail/cover price: $14.95

Our price : $11.96

(You save $2.99!)

About this book:

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton volume 10

The Orient: Its Legacy to the West

by Paul Brunton

A fascinating view of traditional and contemporary Eastern life, customs, arts, philosophies, and spiritual leaders — with an eye to what East and West are teaching one another

Subjects: Spirituality, Adventure

5.75 x 8.5, softcover

(hardcover is available)

272 pages

ISBN 10: 0-943914-33-7

ISBN 13: 978-0-943914-33-6

Book Details

This volume offers a sympathetic and often fascinating view of contemporary and traditional customs, arts, architecture, philosophies, and spiritual leaders of the East. Often reading like a colorful travelogue, it has sections on India, China, Angkor Wat, Ceylon, Japan, Egypt, Tibet, and other Himalayan countries.

It highlights what East and West can (and must) learn from and teach one another as we stumble toward global community.

Includes notes on great teachers and schools of thought.

Category Fifteen: THE ORIENT

INTRODUCTION

1. MEETINGS OF EAST AND WEST

General interest

Value of Eastern thought

Modern opportunities

Western arrogance

Romantic glamour

Western assimilation of Eastern thought

Differences between East and West

Decline of traditional East

Reciprocal West-East impact

Parallels between East and West

Universality of truth

East-West synthesis

2. INDIA

Images of environment, culture, history

Spiritual condition of modern India

India's change and modernization

Caste

General and comparative

Buddha, Buddhism

Vedanta, Hinduism

Shankara

Ramana Maharshi

Aurobindo

Atmananda

Krishnamurti

Gandhi

Ananda Mayee

Ramakrishna, Vivekananda

Other Indian teachers and schools

Himalayan region

3. CHINA, TIBET, JAPAN

General notes on China

Taoism

Confucius, Confucianism, neo-Confucianism

Ch'an Buddhism

Japan

Tibet

4. CEYLON, ANGKOR WAT, BURMA, JAVA

Ceylon

Angkor Wat

Burma

Java

5. ISLAMIC CULTURES, EGYPT

Islamic cultures

Egypt

6. RELATED ENTRIES

Mount Athos

Greece

Christianity and the East

“. . . a veritable treasure-trove of philosophic-spiritual wisdom.” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

“. . . sensible and compelling. His work can stand beside that of such East-West bridges as Merton, Huxley, Suzuki, Watts, and Radhakrishnan. It should appeal to anyone concerned personally and academically with issues of spirituality.” —Choice

“Vigorous, clear-minded and independent . . . a synthesis of Eastern mysticism and Western rationality. . . A rich volume.” —Library Journal

“. . . a great gift to us Westerners who are seeking the spiritual.” —Charles T. Tart

“A person of rare intelligence. . . thoroughly alive, and whole in the most significant, 'holy' sense of the word.” —Yoga Journal

For more reviews of the Notebooks series, click here

The Orient has three distinct elements. Chapter one consists primarily of inspiring reflections on the value of Eastern thought in general, differences and parallels between Eastern and Western cultures, and how changes in both hemispheres are pointing toward the birth of a new and necessarily creative world-culture that will integrate the best values of ancient and modern, mystical and scientific cultures worldwide.

Turning next to specific elements within Oriental culture, the book reflects one major editorial decision. The entries in this section of The Notebooks can be approached in a variety of ways. The two most obvious alternatives involve choosing between a structure that reflects primarily geographic distinctions and one that reflects religious or ideological ones. We could, for example, have gathered together all the notes on Buddhism in one place. Instead, we distributed them to the various countries with which they are associated. This geographical structure seems more in keeping with the "travel book'' style of P.B.'s earlier writings. It also delivers a more direct view into the world-traveling, adventurous side of P.B. than the more academic ideological structure was able to give. Consequently, chapters two through five explore traditional elements and contemporary conditions in a variety of Oriental cultures.

The final chapter, which we have called "Related Entries,'' posed something of a problem in light of P.B.'s title for this category (The Orient) and the printed edition's working subtitle (Its Legacy to the West). P.B. had sprinkled these interesting entries throughout his primarily Asiatic notes, and clearly he had some intention to use them in relation to that material. Had he woven together the various themes and ideas in this volume, he would undoubtedly have found a better way to integrate them into this section than we have done. Rather than to take great liberties with where to place them, however, we have simply acknowledged that they are related and have gathered them together.

Editorial conventions here are the same as stated in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that it also appears in Perspectives, the introductory volume to this series.

From chapter 1: MEETINGS OF EAST AND WEST

303

The medieval European monk with his tonsured head and dark brown gown is the parallel of the Indian ascetic with his long hair and reddish-yellow robe.

304

The ancient mysticism of India is co-operant with the mysticism of medieval Europe in forwarding these same truths.

305

We in the West have our own prophets who can match with the East for amiable foolishness. In both hemispheres the prophets are usually linked up with a tale of marvels.

306

It is quite inaccurate to talk of the ascetic-minded East as against the sensual-minded West. In the matter of sexual passion, let me say bluntly that the inhabitants of Egypt, of Arabia, of Persia, of India, and of China do not lag one whit behind the inhabitants of any European or American land I have known. How else explain the forty million population rise in India alone from census to census?

307

The would-be holy man who squats on a piece of rug in his forest hut is not so remote as it may seem from his modern counterpart who sits on a foam-rubber-filled cushion in his contemporary-styled apartment.

308

The sword suspended by a hair over Damocles' head at a banquet in ancient Syracuse was intended to demonstrate and symbolize how precarious was the happiness of those seated there. Prince Gautama was carefully sheltered by his parents from the sights of human suffering. So when, in his twenties, he saw for the first time a sick man, a dead man, and a decrepit old man, he was filled with horror and renounced the world of royal luxury to become a monk. Unhappy and searching for peace of mind, he wandered through Northern India. From Syracuse to Benares is a long distance, but we see that from Greek speculation on the value of human existence to Indian reflection upon it is quite a short one.

309

The Existentialist attitude existed in the West before the war but did not get any acceptance until the horrors of war made men think of the darker side of human existence. Long before Sartre, it could be found in the writings of the Dane Kierkegaard, the German Heidegger, and the Frenchman de Senancourt. But longer still before these men put it forward, Gautama the Buddha did the same. And, whereas Sartre distorted and exaggerated his facts, Gautama dealt with them in a juster and more positive manner. And the condition of nothingness to which Sartre aspired was metaphysically different from the Buddha's Nirvana.

310

Lao Tzu's teaching, like Socrates', rejects authority; but Confucius', like Plato's, reveres it. Each attitude has its correctness, depending upon historical or local circumstances; but for most individuals an equilibrium between them seems best.

From chapter 2: INDIA

414

Ramana Maharshi was one of those few men who make their appearance on this earth from time to time and who are unique, themselves alone - not copies of anyone else - and who contribute something to the world's spiritual welfare that no one else has contributed in quite the same way.

415

For much of each day the Maharshi was an unspectacular person. But when the pentecostal light touched his mind and radiated from his eyes, he became not merely a different, but a superior being. There was something almost supernatural about this change. It was plain for anyone to see that he was animated by some power, being, or presence other than his usual self. Yet it did not last and could not last. The light departed again, and he himself fell back into ordinariness.

416

Sri Ramana Maharshi is certainly more than a mystic and well worthy of being honoured as a sage. He knows the Real.

417

There are few men of whom one may write with assured conviction that their integrity was unchallengeable and their truthfulness absolute, but Ramana Maharshi was unquestionably one of them.

418

Ramana Maharshi: Sometimes one felt in the presence of a visitor from another planet, at other times with a being of another species.

419

The white loincloth which Ramana Maharshi usually wore served him for most of the year, except during the cooler nights of the mild South Indian winter, when he added a shawl. He had few other possessions. I remember a fountain pen, the old-fashioned liquid ink filling-with-a-glass-syringe type. With this he did his writing. There was also a hollowed-out coconut shell or gourd painted black, in which he carried water for ablutions. He had little more and did not seem to want anything else. The most impressive physical feature about him was the strange look that came over his eyes during meditation, and he usually meditated with open eyes. If they looked directly at you, the power behind them seemed quite penetrative; but most often they seemed to be looking into space, somewhat aside from you, but very fixed, indrawn and abstracted, and yet aware.

420

When Ramana Maharshi was displeased with anyone, he kept his eyes averted and looked to one side of or away from that person. It was as though he did not want, even by accident, let alone purposely, to meet his glance and give him darshan.

421

When he went into these meditative abstractions, the expression in his eyes and even face changed markedly. The eyes shone strangely, mystically, and testified, so far as any bodily organ could, to awareness of the Reality behind this world-dream.

422

Gazing upon this man whose viewless eyes are gazing upon infinity, I thought of Aristotle's daring advice, "Let us live as if we were immortal." Here was someone who had never heard of Aristotle, but who was following this counsel to the last letter.

In his own words:

“Writing, which is an exercise of the intellect to some, is an act of worship to me. I rise from my desk in the same mood as that in which I leave an hour of prayer in an old cathedral, or of meditation in a little wood . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 143

“P.B. as a private person does not count. There are hundreds of millions of such persons anyway. What is one man and his quest? P.B.’s personal experiences and views are not of any particular importance or special consequence. What happens to the individual man named P.B. is a matter of no account to anyone except himself. But what happens to the hundreds of thousands of spiritual seekers today who are following the same path that he pioneered is a serious matter and calls for prolonged consideration. Surely the hundreds of thousands of Western seekers who stand behind him and whom indeed, in one sense, he represents, do count. P.B. as a symbol of the scattered group of Western truth-seekers who, by following his writings so increasingly and so eagerly, virtually follow him also, does count. He personifies their aspirations, their repulsion from materialism and attraction toward mysticism, their interest in Oriental wisdom and their shepherdless state. As a symbol of this Western movement of thought, he is vastly greater than himself. In his mind and person the historic need for a new grasp of the contemporary spiritual problem found a plain-speaking voice . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 145

Learn more about Paul Brunton through articles at the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation web site

Electronic versions of this book are available from all major (Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, etc.) and most smaller ebook vendors. Please don't try to order ebooks directly from us, as we are not yet able to deliver anything to you in a preferred electronic format.

To see all our Paul Brunton titles, scroll down to The Complete Paul Brunton Opus below.

To see and/or order individual volumes in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, hover your mouse over the specific cover in the Notebooks section of Complete Paul Brunton Opus below, then click on Details in the box that appears within it.

Click here to see or order the complete set of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

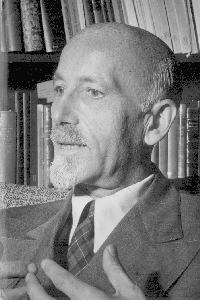

Paul Brunton helps us hear the melody behind the medley of today's "spiritual marketplace." His late writings raise the bar for what we can expect of spiritual teachings and teachers, and what we can do for ourselves. Born in London in 1898, he soon became a leading pioneer of much of what we now take for granted. He traveled widely throughout the world (long before it was fashionable) to meet living masters of various traditions with whom he then lived and studied. His eleven early books from 1934–1952 shared much of what he learned, and helped set the stage for dramatic east-west exchanges of the late 20th century. Paul Brunton left more than 10,000 pages of enormously helpful new work in notebooks he reserved for posthumous publication, much of which is now available as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. See "The Complete Paul Brunton Opus" in blue below to see his many works available on this site. You can also search on Paul Brunton in the search bar to browse the selections, or click on a link below for specific connections.

Click here for an article about Paul Brunton.

Click here for The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

To access small theme-based books compiled from Paul Brunton's writings, scroll down to Derived from the Notebooks below.

To access Paul Brunton's early writings, published from 1934–1952, scroll down to Paul Brunton's Early Works below.

To access commentaries on Paul Brunton and his work by his leading student, Anthony Damiani, as well as other writings about Paul Brunton and/or his work, scroll down to Commentaries and Reflections on Paul Brunton and His Work below.

Book Details

This volume offers a sympathetic and often fascinating view of contemporary and traditional customs, arts, architecture, philosophies, and spiritual leaders of the East. Often reading like a colorful travelogue, it has sections on India, China, Angkor Wat, Ceylon, Japan, Egypt, Tibet, and other Himalayan countries.

It highlights what East and West can (and must) learn from and teach one another as we stumble toward global community.

Includes notes on great teachers and schools of thought.

Category Fifteen: THE ORIENT

INTRODUCTION

1. MEETINGS OF EAST AND WEST

General interest

Value of Eastern thought

Modern opportunities

Western arrogance

Romantic glamour

Western assimilation of Eastern thought

Differences between East and West

Decline of traditional East

Reciprocal West-East impact

Parallels between East and West

Universality of truth

East-West synthesis

2. INDIA

Images of environment, culture, history

Spiritual condition of modern India

India's change and modernization

Caste

General and comparative

Buddha, Buddhism

Vedanta, Hinduism

Shankara

Ramana Maharshi

Aurobindo

Atmananda

Krishnamurti

Gandhi

Ananda Mayee

Ramakrishna, Vivekananda

Other Indian teachers and schools

Himalayan region

3. CHINA, TIBET, JAPAN

General notes on China

Taoism

Confucius, Confucianism, neo-Confucianism

Ch'an Buddhism

Japan

Tibet

4. CEYLON, ANGKOR WAT, BURMA, JAVA

Ceylon

Angkor Wat

Burma

Java

5. ISLAMIC CULTURES, EGYPT

Islamic cultures

Egypt

6. RELATED ENTRIES

Mount Athos

Greece

Christianity and the East

“. . . a veritable treasure-trove of philosophic-spiritual wisdom.” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

“. . . sensible and compelling. His work can stand beside that of such East-West bridges as Merton, Huxley, Suzuki, Watts, and Radhakrishnan. It should appeal to anyone concerned personally and academically with issues of spirituality.” —Choice

“Vigorous, clear-minded and independent . . . a synthesis of Eastern mysticism and Western rationality. . . A rich volume.” —Library Journal

“. . . a great gift to us Westerners who are seeking the spiritual.” —Charles T. Tart

“A person of rare intelligence. . . thoroughly alive, and whole in the most significant, 'holy' sense of the word.” —Yoga Journal

For more reviews of the Notebooks series, click here

The Orient has three distinct elements. Chapter one consists primarily of inspiring reflections on the value of Eastern thought in general, differences and parallels between Eastern and Western cultures, and how changes in both hemispheres are pointing toward the birth of a new and necessarily creative world-culture that will integrate the best values of ancient and modern, mystical and scientific cultures worldwide.

Turning next to specific elements within Oriental culture, the book reflects one major editorial decision. The entries in this section of The Notebooks can be approached in a variety of ways. The two most obvious alternatives involve choosing between a structure that reflects primarily geographic distinctions and one that reflects religious or ideological ones. We could, for example, have gathered together all the notes on Buddhism in one place. Instead, we distributed them to the various countries with which they are associated. This geographical structure seems more in keeping with the "travel book'' style of P.B.'s earlier writings. It also delivers a more direct view into the world-traveling, adventurous side of P.B. than the more academic ideological structure was able to give. Consequently, chapters two through five explore traditional elements and contemporary conditions in a variety of Oriental cultures.

The final chapter, which we have called "Related Entries,'' posed something of a problem in light of P.B.'s title for this category (The Orient) and the printed edition's working subtitle (Its Legacy to the West). P.B. had sprinkled these interesting entries throughout his primarily Asiatic notes, and clearly he had some intention to use them in relation to that material. Had he woven together the various themes and ideas in this volume, he would undoubtedly have found a better way to integrate them into this section than we have done. Rather than to take great liberties with where to place them, however, we have simply acknowledged that they are related and have gathered them together.

Editorial conventions here are the same as stated in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that it also appears in Perspectives, the introductory volume to this series.

From chapter 1: MEETINGS OF EAST AND WEST

303

The medieval European monk with his tonsured head and dark brown gown is the parallel of the Indian ascetic with his long hair and reddish-yellow robe.

304

The ancient mysticism of India is co-operant with the mysticism of medieval Europe in forwarding these same truths.

305

We in the West have our own prophets who can match with the East for amiable foolishness. In both hemispheres the prophets are usually linked up with a tale of marvels.

306

It is quite inaccurate to talk of the ascetic-minded East as against the sensual-minded West. In the matter of sexual passion, let me say bluntly that the inhabitants of Egypt, of Arabia, of Persia, of India, and of China do not lag one whit behind the inhabitants of any European or American land I have known. How else explain the forty million population rise in India alone from census to census?

307

The would-be holy man who squats on a piece of rug in his forest hut is not so remote as it may seem from his modern counterpart who sits on a foam-rubber-filled cushion in his contemporary-styled apartment.

308

The sword suspended by a hair over Damocles' head at a banquet in ancient Syracuse was intended to demonstrate and symbolize how precarious was the happiness of those seated there. Prince Gautama was carefully sheltered by his parents from the sights of human suffering. So when, in his twenties, he saw for the first time a sick man, a dead man, and a decrepit old man, he was filled with horror and renounced the world of royal luxury to become a monk. Unhappy and searching for peace of mind, he wandered through Northern India. From Syracuse to Benares is a long distance, but we see that from Greek speculation on the value of human existence to Indian reflection upon it is quite a short one.

309

The Existentialist attitude existed in the West before the war but did not get any acceptance until the horrors of war made men think of the darker side of human existence. Long before Sartre, it could be found in the writings of the Dane Kierkegaard, the German Heidegger, and the Frenchman de Senancourt. But longer still before these men put it forward, Gautama the Buddha did the same. And, whereas Sartre distorted and exaggerated his facts, Gautama dealt with them in a juster and more positive manner. And the condition of nothingness to which Sartre aspired was metaphysically different from the Buddha's Nirvana.

310

Lao Tzu's teaching, like Socrates', rejects authority; but Confucius', like Plato's, reveres it. Each attitude has its correctness, depending upon historical or local circumstances; but for most individuals an equilibrium between them seems best.

From chapter 2: INDIA

414

Ramana Maharshi was one of those few men who make their appearance on this earth from time to time and who are unique, themselves alone - not copies of anyone else - and who contribute something to the world's spiritual welfare that no one else has contributed in quite the same way.

415

For much of each day the Maharshi was an unspectacular person. But when the pentecostal light touched his mind and radiated from his eyes, he became not merely a different, but a superior being. There was something almost supernatural about this change. It was plain for anyone to see that he was animated by some power, being, or presence other than his usual self. Yet it did not last and could not last. The light departed again, and he himself fell back into ordinariness.

416

Sri Ramana Maharshi is certainly more than a mystic and well worthy of being honoured as a sage. He knows the Real.

417

There are few men of whom one may write with assured conviction that their integrity was unchallengeable and their truthfulness absolute, but Ramana Maharshi was unquestionably one of them.

418

Ramana Maharshi: Sometimes one felt in the presence of a visitor from another planet, at other times with a being of another species.

419

The white loincloth which Ramana Maharshi usually wore served him for most of the year, except during the cooler nights of the mild South Indian winter, when he added a shawl. He had few other possessions. I remember a fountain pen, the old-fashioned liquid ink filling-with-a-glass-syringe type. With this he did his writing. There was also a hollowed-out coconut shell or gourd painted black, in which he carried water for ablutions. He had little more and did not seem to want anything else. The most impressive physical feature about him was the strange look that came over his eyes during meditation, and he usually meditated with open eyes. If they looked directly at you, the power behind them seemed quite penetrative; but most often they seemed to be looking into space, somewhat aside from you, but very fixed, indrawn and abstracted, and yet aware.

420

When Ramana Maharshi was displeased with anyone, he kept his eyes averted and looked to one side of or away from that person. It was as though he did not want, even by accident, let alone purposely, to meet his glance and give him darshan.

421

When he went into these meditative abstractions, the expression in his eyes and even face changed markedly. The eyes shone strangely, mystically, and testified, so far as any bodily organ could, to awareness of the Reality behind this world-dream.

422

Gazing upon this man whose viewless eyes are gazing upon infinity, I thought of Aristotle's daring advice, "Let us live as if we were immortal." Here was someone who had never heard of Aristotle, but who was following this counsel to the last letter.

In his own words:

“Writing, which is an exercise of the intellect to some, is an act of worship to me. I rise from my desk in the same mood as that in which I leave an hour of prayer in an old cathedral, or of meditation in a little wood . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 143

“P.B. as a private person does not count. There are hundreds of millions of such persons anyway. What is one man and his quest? P.B.’s personal experiences and views are not of any particular importance or special consequence. What happens to the individual man named P.B. is a matter of no account to anyone except himself. But what happens to the hundreds of thousands of spiritual seekers today who are following the same path that he pioneered is a serious matter and calls for prolonged consideration. Surely the hundreds of thousands of Western seekers who stand behind him and whom indeed, in one sense, he represents, do count. P.B. as a symbol of the scattered group of Western truth-seekers who, by following his writings so increasingly and so eagerly, virtually follow him also, does count. He personifies their aspirations, their repulsion from materialism and attraction toward mysticism, their interest in Oriental wisdom and their shepherdless state. As a symbol of this Western movement of thought, he is vastly greater than himself. In his mind and person the historic need for a new grasp of the contemporary spiritual problem found a plain-speaking voice . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 145

Learn more about Paul Brunton through articles at the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation web site

Electronic versions of this book are available from all major (Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, etc.) and most smaller ebook vendors. Please don't try to order ebooks directly from us, as we are not yet able to deliver anything to you in a preferred electronic format.

To see all our Paul Brunton titles, scroll down to The Complete Paul Brunton Opus below.

To see and/or order individual volumes in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, hover your mouse over the specific cover in the Notebooks section of Complete Paul Brunton Opus below, then click on Details in the box that appears within it.

Click here to see or order the complete set of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

About Paul Brunton

Paul Brunton helps us hear the melody behind the medley of today's "spiritual marketplace." His late writings raise the bar for what we can expect of spiritual teachings and teachers, and what we can do for ourselves. Born in London in 1898, he soon became a leading pioneer of much of what we now take for granted. He traveled widely throughout the world (long before it was fashionable) to meet living masters of various traditions with whom he then lived and studied. His eleven early books from 1934–1952 shared much of what he learned, and helped set the stage for dramatic east-west exchanges of the late 20th century. Paul Brunton left more than 10,000 pages of enormously helpful new work in notebooks he reserved for posthumous publication, much of which is now available as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. See "The Complete Paul Brunton Opus" in blue below to see his many works available on this site. You can also search on Paul Brunton in the search bar to browse the selections, or click on a link below for specific connections.

Click here for an article about Paul Brunton.

Click here for The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

To access small theme-based books compiled from Paul Brunton's writings, scroll down to Derived from the Notebooks below.

To access Paul Brunton's early writings, published from 1934–1952, scroll down to Paul Brunton's Early Works below.

To access commentaries on Paul Brunton and his work by his leading student, Anthony Damiani, as well as other writings about Paul Brunton and/or his work, scroll down to Commentaries and Reflections on Paul Brunton and His Work below.

The Complete Paul Brunton Opus:

Paul Brunton's most mature work, in the order he specified for posthumous publication.

Smaller books on popular/timely themes, developed from the Notebooks and published posthumously.

Paul Brunton's works published during his lifetime from 1934-1952

Commentaries/Reflections by other authors on Paul Brunton or his works.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)