The Notebooks of Paul Brunton volume 15

Advanced Contemplation

The Peace within You By Paul Brunton

Retail/cover price: $24.95

Our price : $19.96

(You save $4.99!)

About this book:

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton volume 15

Advanced Contemplation

The Peace within You

by Paul Brunton

"Follow this invisible thread of tender holy feeling, keep attention close to it, do not let other things distract or bring you away from it. For at its end is entry into Awareness." —Paul Brunton

Subjects: Spirituality, Meditation, Short Path

5.75 x 8.5, softcover

(hardcover is available)

382 pages

ISBN 10: 0-943914-43-4

ISBN 13: 978-0-943914-43-5

Book Details

Part 1, Advanced Contemplation, offers a direct route to the deepest mystical states — yielding permanent results of a metaphysical, transpersonal, and universal nature. It introduces Short Path (sudden) practices (such as Advaita, Zen, Dzogchen, Mahamudra, Krishnamurti, etc.), develops them, explains why they are so often insufficient, and shows when, how, and in what spirit to use them effectively.

Part 2, The Peace within You, offers an uplifting and invigorating approach to "the peace which passeth understanding" at the core of every human being, showing how its rich serenity can be consciously integrated into daily living.

Category Twenty-three: ADVANCED CONTEMPLATION

INTRODUCTION

1. ENTERING THE SHORT PATH

Begin and end with the goal itself

The practice

Benefits and results

2. PITFALLS AND LIMITATIONS

The truth about sudden enlightenment

Limitations of the Long Path

3. THE DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL

Its significance

4. THE CHANGEOVER TO THE SHORT PATH

The preparation on the Long Path

Making the transition

5. BALANCING THE PATHS

Their contrast and comparison

Their combination and transcendence

6. ADVANCED MEDITATION

Specific exercises for practice

Yoga of the Liberating Smile

Night meditations

Witness exercise

"As If" exercise

Remembrance exercise

7. CONTEMPLATIVE STILLNESS

Experiencing the passage into contemplation

Still the mind

Deepen attention

Yield to Grace

The deepest contemplation

8. THE VOID AS CONTEMPLATIVE EXPERIENCE

Entering the Void

Nirvikalpa Samadhi

Meditation upon the Void

Emerging from the Void

Why Buddha smiled

Category Twenty-four: THE PEACE WITHIN YOU

INTRODUCTION

1. THE SEARCH FOR HAPPINESS

The limitations of life

Philosophic happiness

The heart of joy

2. BE CALM

The goal of tranquillity

In daily life

The qualities of calm

Staying calm

3. PRACTISE DETACHMENT

Turn inward

Solving difficulties

Training mind and heart

True asceticism

Becoming the Witness

Timelessness

Free activity

4. SEEK THE DEEPER STILLNESS

Quiet the ego

The still centre within

The Great Silence

“. . . a veritable treasure-trove of philosophic-spiritual wisdom.” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

“. . . sensible and compelling. His work can stand beside that of such East-West bridges as Merton, Huxley, Suzuki, Watts, and Radhakrishnan. It should appeal to anyone concerned personally and academically with issues of spirituality.” —Choice

“Vigorous, clear-minded and independent . . . a synthesis of Eastern mysticism and Western rationality. . . A rich volume.” —Library Journal

“. . . a great gift to us Westerners who are seeking the spiritual.” —Charles T. Tart

“A person of rare intelligence. . . thoroughly alive, and whole in the most significant, 'holy' sense of the word.” —Yoga Journal

For more reviews of the Notebooks series, click here

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category twenty-three, Advanced Contemplation

With this category, we encounter another major turning point of the quest — the point at which the ego relinquishes the practices and pace to the Overself. On the Long Path we initiate our development through our own effort. For guidance on the Long Path we must rely on our own intelligence and feelings, strengthened by the external influence of friends, teachers, and sacred literature. This point of view is established in category two, Practices for the Quest, and is maintained through the categories that follow, dealing with the nature of this quest, the structure of the ego, the experiences of mysticism, the study of philosophy, and the understanding of mentalism. All these work toward weakening our identification with the ego and strengthening our awareness of the Overself.

The practices and attitudes presented in Advanced Contemplation deepen this contact with the Overself until the ego must surrender to its guidance both in daily life and in meditation. Here we begin the quest anew, with a direct comprehension of the goal for the first time. At last we come to know that nothing else matters, that there is nothing outside the quest. Up to this point the quest may be an intermittent affair, a confusing journey through the misconceptions and misdirections of the ego; hereafter, the student moves in light along the mysterious path of spiritual attainment. This is because the quester is no longer primarily concerned with battling the ego; the focus is now on living always in the presence of the Overself.

Advanced Contemplation explores the nature of this redirection of attention from ego to Overself and shows us how it can be done. Then The Peace Within You shows us how to live inside the quest, inside the stillness of the Overself, once this transition has occurred.

As we look through the topics in The Notebooks, we can see that P.B. considers the quest as ascending through three levels: the physical, the subtle, and the mental. As P.B. examines each level, he alternates between objective understanding and subjective awareness. For example, in The Sensitives (category sixteen) P.B. acquaints us with the misconceptions and ignorance about the psychic realm. This acquaintance prepares the way for The Reverential Life (category eighteen), where we turn our hearts toward the image of the Overself in the subtle plane of interior feeling. P.B. repeats this pattern in categories nineteen through twenty-two: First he defines the characteristics with which mind imbues experience and the nature of the mind itself (nineteen through twenty-one); then he lifts our awareness beyond the mental plane into the intuitive awareness of the Overself (twenty-two).

This pattern of alternating objective and subjective perspectives reaches its conclusion in Advanced Contemplation. On a first reading, this category may appear to have two sections: the first five chapters, which include the definitions of the Short Path and its combination with the Long Path, and the last three chapters, which describe various techniques for advanced meditation, including contemplations of the Void. However, a closer reading will show that this category is a whole.

The difference between the extroverted state of mind, treated in the first five chapters, and the introverted mind, treated in the last three chapters, must become very slight if this stage of the quest is to be successful. In fact, in the next category, The Peace within You, this difference vanishes as completely as it can. This blending of the objective and subjective perspectives is a central point for the interplay of these two categories, which are bound together as one volume in the printed edition. In the opening chapter of Advanced Contemplation, P.B. tells us to begin and end with the goal, to turn 180 degrees around — not away from the ego, but toward the Overself. He tells us to face the Overself always, and in all ways: to orient our daily life and activities towards the achievement of its presence, and to devote our meditations not to its symbols or signs but to itself alone. This single-minded focus on the transcendent Overself naturally draws the extroverted mind and the introverted mind more closely together, since the primary content of either one is now the same. When P.B. describes the Void as a contemplative state, he makes it clear that no sort of subject or object can exist in that state, and that the stillness it generates cannot be accurately described in either context alone.

Another point P.B. makes in Advanced Contemplation is that the Short Path gets its name neither from its speed of attainment nor from its ease of accomplishment, but from the directness of its approach to the quest. Like a solitary ascent of a challenging cliff-face, the Short Path keenly focuses the mind on the demands of spiritual development. This approach is a necessary stage of the quest, and one whose dangers are real if we make the assault unready and unaware. The nature of these risks and remedies is discussed in the second and third chapters. Having made the challenge and the warnings clear, in chapter four P.B. describes exactly how we can make the changeover to the Short Path. Then, in chapter five, P.B. adds his wonderful sense of balance to the picture, pointing out the place of the Long Path's milder approach — as first separate, then interwoven with, and finally combining with the Short Path to become the philosopher's way of life. So P.B. begins by presenting the Short Path as a challenge to the quester, but concludes by stating that the Short Path, when balanced by the Long Path, becomes the "way'' of living in the radiant presence of the Overself.

The chapters of Advanced Contemplation are arranged as a development from simple to more advanced stages of practice. The fundamental stages, however, are only briefly described here, as they have been fully discussed in earlier categories. We recommend that readers review Practices for the Quest (category two) and Meditation (category four) as a part of studying Advanced Contemplation. Category two gives a full consideration of the Long Path; it may be helpful to read chapters one and nine there before reading chapters four and five of the present category. It is likewise especially important to review the section titled "Levels of Absorption'' in the first chapter of Meditation (category four) before reading the meditation exercises and experiences in chapters six through eight of Advanced Contemplation. That section defines and describes all the stages of meditation, right up through advanced contemplation, and gives some indication of how to recognize them. Readers who have already studied Meditation will notice that we have repeated nine paras from that section as a reference guide to P.B.'s description and definition of the various stages of meditation and contemplation; see paras 52–60 in chapter seven, "Contemplative Stillness," below.

We should also mention that chapter three, "The Dark Night of the Soul,'' is not a topic P.B. originally assigned to this category. These paras were originally scattered throughout the various categories. We felt, however, that having all this material in one place would be useful to individuals confronted with this difficult experience, and that the subject — while not exactly belonging in Advanced Contemplation — does depend upon ideas and practices first described here. This artificial gathering of a topic into one place by the editors is very rare in the Notebooks series — almost all topics were originally given their placement into specific categories by P.B.

Editorial conventions here are the same as stated in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that it also appears in Perspectives, the introductory volume to this series.

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category twenty-four, The Peace within You

The chapter titles of The Peace within You summarize nearly all that can be said about this section: The Search for Happiness; Be Calm; Practise Detachment; and Seek the Deeper Stillness. Here we meet the Great Silence of the Overself and the Peace that motivates our desire for happiness — the same Peace that we ultimately find underlying even our greatest sorrows. The difference between categories twenty-three and twenty-four is that the quester is seeking the stillness of the Overself in every part of life in Advanced Contemplation, while in The Peace within You the quester is learning to live inside the stillness. Appropriately, the practices in The Peace within You are designed to create a way of living that doesn't disturb one's awareness of the presence of the Overself.

The difference between these two stages can be seen by comparing the paras on the Witness exercise in chapter six of Advanced Contemplation to the paras titled "Becoming the Witness'' in chapter three of The Peace within You. In the first group, the quester is shown how to bring about the Witness attitude; the second group shows how to apply this attitude in the practice of detachment.

The Peace within You provides a sort of contemplative pause between the revolutionary enterprise of the Short Path and the final challenge of the "Enlightenment which Stays" that emerges in category twenty-five. Even though there is but a short distance in print between these two stages, the length of time between them may prove to be quite long. This is because much of the quester's growth now occurs in silence, and really can't be expressed in thought. So it is fitting that this volume ends with the section titled "The Great Silence.''

Editorial conventions here are the same as stated in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that it also appears in Perspectives, the introductory volume to this series.

Excerpts from Notebooks category twenty-three, Advanced Contemplation

PREFATORY

EVOLUTION IS only an idea within the mind, hence it has the value of something imagined. The reality is that one has never left the heavenly being, but ignorance prevents him from realizing this. To get rid of this ignorance, he must sharpen the mind by constant effort, tranquillize it by meditation, and guide it through the help of a teacher.

WHATEVER PATH a man starts with, he must at the end of it come to the entrance of this path — the destruction of the illusion of the ego and giving up identification with it.

From chapter 1: ENTERING THE SHORT PATH

Begin and end with the goal itself

1

This notion that we must wait and wait while we slowly progress out of enslavement into liberation, out of ignorance into knowledge, out of the present limitations into a future union with the Divine, is only true if we let it be so. But we need not. We can shift our identification from the ego to the Overself in our habitual thinking, in our daily reactions and attitudes, in our response to events and the world. We have thought our way into this unsatisfactory state; we can unthink our way out of it. By incessantly remembering what we really are, here and now at this very moment, we set ourselves free. Why wait for what already is?

2

All other approaches to the goal depend on a dualistic principle, which puts them on a lower plane. But the Short Path is nondual: it begins and ends with the goal itself; its nature is direct and its working is immediate.

3

Consciousness appearing as the person seeks itself. This is its quest. But when it learns and comprehends that it is itself the object of that quest, the person stops not only seeking outside himself but even engaging in the quest itself. Henceforth he lets himself be moved by the Overself's flow.

4

All these substitutes for the truth may appear to be useful stepping-stones to it but in fact they keep him from it, for there is no end to the number of steps he will be able to take since there is no end to the number of ways the human mind can spin out its ideas and fancies. Unless he begins with the end first, he will get lost on the way to it.

From chapter 5: BALANCING THE PATHS

Their contrast and comparison\

2

Most people who start the short path have usually had a glimpse of the Overself, because otherwise they find it too difficult to understand what the short path is about. The long path, through its studies and practices, is the period of preparation for the advanced quest. It is called the long path because there is much work to be done on it and much development of character and emotions to go through. After some measure of this preparation the aspirants enter the short path to complete this work. This takes a comparatively much shorter time and, as it has the possibility of yielding the full self-enlightenment at any moment, it ends suddenly. What they are trying to do on the long path continues by itself once they have entered fully on the short path. On the long path they are concerned with the personal ego and as a result give the negative thoughts their attention. On the short path they refuse to accept these negatives and instead look to the Overself. Thus the struggles will disappear. This change of attitude is called "voiding" them. The moment such negative ideas and feelings appear, then instead of using the long path method of concentrating on the opposite kind of thought, such as calmness instead of anger, the short path way simply drops the negative idea into the Void, the Nothingness, and forgets it. Now such a change can only be brought about by doing it quickly and firmly and turning to the Overself. Constant remembrance of the Overself has to be done all the way through the short path. The long path works on the ego; but the short path uses the result of that work, which prepared them to come into communion with the Overself and become receptive to its presence, which includes its grace. In order to understand the short path, it might be helpful to compare it to the long path which consists of a series of exercises and efforts which gradually develops concentration and character and knowledge. But the long path does not lead to the goal. On the long path you often measure your own progress. It is an endless path because there will always be new circumstances which bring new temptations and trials and confront the aspirant with new challenges. No matter how spiritual the ego becomes it does not enter the whitest light, but remains in the greyish light. On the long path you must deal with the urges of interference arising from the lower self and the negativity which enters from the surrounding environment. But the efforts on the long path will at last invoke the grace, which opens the perspective of the short path.

The short path is not an exercise but an inner standpoint to invoke, a state of consciousness where one comes closer or finds peace in the Overself. There are, however, two exercises which can be of help to lead to the short path, but they have quite a different character than the exercises on the long path. The short path takes less time because the aspirant turns around and faces the goal directly. The short path means that you begin to try to remember to live in the rarefied atmosphere of the Overself instead of worrying about the ego and measuring its spiritual development. You learn to trust more and more in the Higher Power. On the short path you ignore negativity and turn around 180 degrees, from the ego to the Overself. The visitations of the Overself are heralded through devotional feeling, but also through intuitive thought and action. Often the two paths can be treaded simultaneously, but not necessarily equally.

Often the aspirant is not ready to start these two exercises until after one or several glimpses of the Overself.

The "remembrance exercise" consists of trying to recall the glimpse of the Overself, not only during the set meditation periods but also in each moment during the whole working span of the day - in the same way as a mother who has lost her child can not let go of the thought of it no matter what she is doing outwardly, or as a lover who constantly holds the vivid image of the beloved in the back of his mind. In a similar way, you keep the memory of the Overself alive during this exercise and let it shine in the background while you go about your daily work. But the spirit of the exercise is not to be lost. It must not be mechanical and cold. The time may come later when the remembrance will cease as a consciously and deliberately willed exercise and pass by itself into a state which will be maintained without the help of the ego's will.

The remembrance is a necessary preparation for the second exercise, in which you try to obtain an immediate identification with the Overself. Just as an actor identifies with the role he plays on the stage, you act think and live during the daily life "as if" you were the Overself. This exercise is not merely intellectual but also includes feeling and intuitive action. It is an act of creative imagination in which by turning directly to playing the part of the Overself you make it possible for its grace to come more and more into your life.

From chapter 7: CONTEMPLATIVE STILLNESS

233

A point is reached where the seeker must stop making a thought of the Overself, or he will defeat himself and ensure inability to go beyond the intellect into the Overself. At this point he is required to enter the Stillness.

314

The fear of annihilation which comes to a number of persons who meditate deeply enough, and which forces them to withdraw themselves from the practice for that session, is justifiable. There is an experience which seems to be equivalent to self-obliteration. Nevertheless it is not the end of existence, for it is followed by an entry into the beautiful white light, bringing an immense feeling of space and goodwill, of harmony and liberation from all that is low, of peace and compassion. The whole experience is so vivid, so real, so convincing — all through from beginning to end — that whether or not it recurs, it will remain forever in his memory. It has also a strange power when recalled years afterwards in moments of trouble and distress to provide inner help and support.

315

This transparent light-world is the source of creation, the cosmic birthplace, the home of dazzling primal energy. Galaxies, universes, suns, and planets come forth from here. The revelatory, blissful vision of God's Form may happen only once in a lifetime. Beyond it all is God without Form — the still void.

322

The novice must cautiously feel his way back from the divine centre at the end of his period of meditation to the plane of normal activity. This descent or return must be carefully negotiated. If he is not careful he may easily and needlessly lose the fruit of his attainment. An exercise to accomplish this, to bring the meditator slowly back to earth and to prepare him for the external life of inspired activity, is the following one: very slowly opening and shutting eyelids several times. Those moments immediately following cessation of meditation are equally as important as the period preceding. They are of crucial importance in fact. For in those few minutes he may have lost much of what he gained during the whole period. Hold the state attained as gently and preciously as you would hold a baby. Hold to the centre and do not stray from it. Such a state the yogis call sahaja samadhi: despite all moving about there is non-action, for the heart is free.

Excerpts from Notebooks category twenty-four, The Peace within You

PREFATORY

For the person who is not a complete beginner, who has attained a modest proficiency in the inner life, there is no real contradiction between the inner and the outer life. The one kind of existence will be inspired by the other. Neither despising the world nor becoming lost in it, he moves in poised safety through it. Outwardly we live and have to live in the very midst of cruel struggle and grievous conflict, for we share the planet's karma; but inwardly we can live by striking contrast in an intense stillness, a consecrated peace, a sublime security. The central stillness is always there, whether we are absorbed in bustling activity or not. Hence a part of this training consists in becoming conscious of its presence. Indeed only by bringing the mystical realization into the active life of the wakeful world can it attain its own fullness. The peaceful state must not only be attained during meditation, but also sustained during action.

From chapter 1: THE SEARCH FOR HAPPINESS

The heart of joy

74

If you investigate the matter deeply enough and widely enough, you will find that happiness eludes nearly all men despite the fact that they are forever seeking it. The fortunate and successful few are those who have stopped seeking with the ego alone and allow the search to be directed inwardly by the higher self. They alone can find a happiness unblemished by defects or deficiencies, a Supreme Good which is not a further source of pain and sorrow but an endless source of satisfaction and peace.(P)

75

Pleasure is satisfaction derived from the things and persons outside us. Happiness is satisfaction derived from the core of deepest being inside us. Because we get our pleasures through the five senses, they are more exciting and are sharper, more vivid, than the diffused self-induced thoughts and feelings which bring us happiness. In short, pleasure is of the body whereas something quite immaterial and impalpable is the source of our happiness. This is not to say that all pleasures are to be ascetically rejected, but that whereas we are helplessly dependent for them on some object or some person, we are dependent only on ourselves for happiness.(P)

From chapter 4: SEEK THE DEEPER STILLNESS

1

When the personal ego's thoughts and desires are stripped off, we behold ourselves as we were in the first state and as we shall be in the final one. We are then the Overself alone, in its Godlike solitude and stillness.(P)

2

One feels gathered into the depths of the silence, enfolded by it and then, hidden within it, intuits the mysterious inexplicable invisible and higher power which must remain forever nameless.

3

A life with this infinite stillness as its background and centre seems as remote from the common clay of everyday human beings, and especially from their urban infatuation with noise and movement, as the asteroids.

4

This stillness is the godlike part of every human being. In failing to look for it, he fails to make the most of his possibilities. If, looking, he misses it on the way, this happens because it is a vacuity: there is simply nothing there! That means no things, not even mental things, that is, thoughts.(P)

5

The spirit (Brahman) is NOT the stillness, but is found by humans who are in the precondition of stillness. The latter is their human reaction to Brahman's presence coming into their field of awareness.(P)

6

That beautiful state wherein the mind recognizes itself for what it is, wherein all activity is stilled except that of awareness alone, and even then it is an awareness without an object — this is the heart of the experience.(P)

In his own words:

“Writing, which is an exercise of the intellect to some, is an act of worship to me. I rise from my desk in the same mood as that in which I leave an hour of prayer in an old cathedral, or of meditation in a little wood . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 143

“P.B. as a private person does not count. There are hundreds of millions of such persons anyway. What is one man and his quest? P.B.’s personal experiences and views are not of any particular importance or special consequence. What happens to the individual man named P.B. is a matter of no account to anyone except himself. But what happens to the hundreds of thousands of spiritual seekers today who are following the same path that he pioneered is a serious matter and calls for prolonged consideration. Surely the hundreds of thousands of Western seekers who stand behind him and whom indeed, in one sense, he represents, do count. P.B. as a symbol of the scattered group of Western truth-seekers who, by following his writings so increasingly and so eagerly, virtually follow him also, does count. He personifies their aspirations, their repulsion from materialism and attraction toward mysticism, their interest in Oriental wisdom and their shepherdless state. As a symbol of this Western movement of thought, he is vastly greater than himself. In his mind and person the historic need for a new grasp of the contemporary spiritual problem found a plain-speaking voice . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 145

Learn more about Paul Brunton through articles at the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation web site

Electronic versions of this book are available from all major (Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, etc.) and most smaller ebook vendors. Please don't try to order ebooks directly from us, as we are not yet able to deliver anything to you in a preferred electronic format.

To see all our Paul Brunton titles, scroll down to The Complete Paul Brunton Opus below.

Click here to see or order the complete set of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

Paul Brunton helps us hear the melody behind the medley of today's "spiritual marketplace." His late writings raise the bar for what we can expect of spiritual teachings and teachers, and what we can do for ourselves. Born in London in 1898, he soon became a leading pioneer of much of what we now take for granted. He traveled widely throughout the world (long before it was fashionable) to meet living masters of various traditions with whom he then lived and studied. His eleven early books from 1934–1952 shared much of what he learned, and helped set the stage for dramatic east-west exchanges of the late 20th century. Paul Brunton left more than 10,000 pages of enormously helpful new work in notebooks he reserved for posthumous publication, much of which is now available as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. See "The Complete Paul Brunton Opus" in blue below to see his many works available on this site. You can also search on Paul Brunton in the search bar to browse the selections, or click on a link below for specific connections.

Click here for an article about Paul Brunton.

Click here for The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

To access small theme-based books compiled from Paul Brunton's writings, scroll down to Derived from the Notebooks below.

To access Paul Brunton's early writings, published from 1934–1952, scroll down to Paul Brunton's Early Works below.

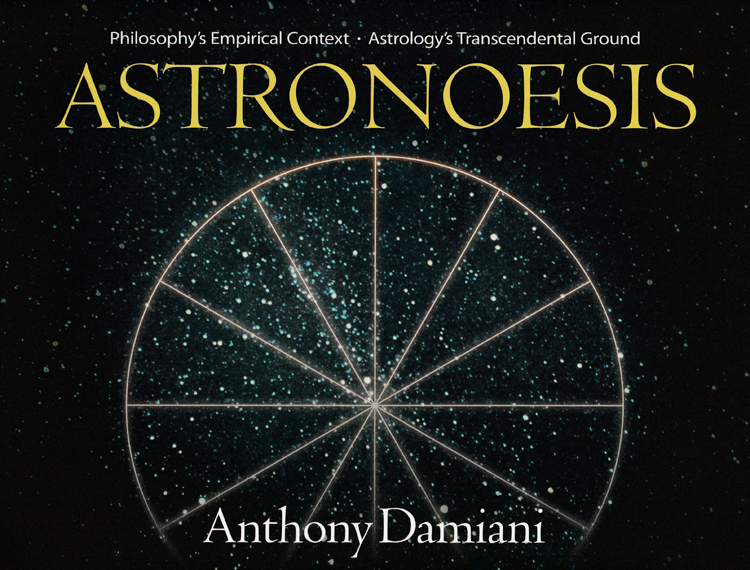

To access commentaries on Paul Brunton and his work by his leading student, Anthony Damiani, as well as other writings about Paul Brunton and/or his work, scroll down to Commentaries and Reflections on Paul Brunton and His Work below.

Book Details

Part 1, Advanced Contemplation, offers a direct route to the deepest mystical states — yielding permanent results of a metaphysical, transpersonal, and universal nature. It introduces Short Path (sudden) practices (such as Advaita, Zen, Dzogchen, Mahamudra, Krishnamurti, etc.), develops them, explains why they are so often insufficient, and shows when, how, and in what spirit to use them effectively.

Part 2, The Peace within You, offers an uplifting and invigorating approach to "the peace which passeth understanding" at the core of every human being, showing how its rich serenity can be consciously integrated into daily living.

Category Twenty-three: ADVANCED CONTEMPLATION

INTRODUCTION

1. ENTERING THE SHORT PATH

Begin and end with the goal itself

The practice

Benefits and results

2. PITFALLS AND LIMITATIONS

The truth about sudden enlightenment

Limitations of the Long Path

3. THE DARK NIGHT OF THE SOUL

Its significance

4. THE CHANGEOVER TO THE SHORT PATH

The preparation on the Long Path

Making the transition

5. BALANCING THE PATHS

Their contrast and comparison

Their combination and transcendence

6. ADVANCED MEDITATION

Specific exercises for practice

Yoga of the Liberating Smile

Night meditations

Witness exercise

"As If" exercise

Remembrance exercise

7. CONTEMPLATIVE STILLNESS

Experiencing the passage into contemplation

Still the mind

Deepen attention

Yield to Grace

The deepest contemplation

8. THE VOID AS CONTEMPLATIVE EXPERIENCE

Entering the Void

Nirvikalpa Samadhi

Meditation upon the Void

Emerging from the Void

Why Buddha smiled

Category Twenty-four: THE PEACE WITHIN YOU

INTRODUCTION

1. THE SEARCH FOR HAPPINESS

The limitations of life

Philosophic happiness

The heart of joy

2. BE CALM

The goal of tranquillity

In daily life

The qualities of calm

Staying calm

3. PRACTISE DETACHMENT

Turn inward

Solving difficulties

Training mind and heart

True asceticism

Becoming the Witness

Timelessness

Free activity

4. SEEK THE DEEPER STILLNESS

Quiet the ego

The still centre within

The Great Silence

“. . . a veritable treasure-trove of philosophic-spiritual wisdom.” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

“. . . sensible and compelling. His work can stand beside that of such East-West bridges as Merton, Huxley, Suzuki, Watts, and Radhakrishnan. It should appeal to anyone concerned personally and academically with issues of spirituality.” —Choice

“Vigorous, clear-minded and independent . . . a synthesis of Eastern mysticism and Western rationality. . . A rich volume.” —Library Journal

“. . . a great gift to us Westerners who are seeking the spiritual.” —Charles T. Tart

“A person of rare intelligence. . . thoroughly alive, and whole in the most significant, 'holy' sense of the word.” —Yoga Journal

For more reviews of the Notebooks series, click here

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category twenty-three, Advanced Contemplation

With this category, we encounter another major turning point of the quest — the point at which the ego relinquishes the practices and pace to the Overself. On the Long Path we initiate our development through our own effort. For guidance on the Long Path we must rely on our own intelligence and feelings, strengthened by the external influence of friends, teachers, and sacred literature. This point of view is established in category two, Practices for the Quest, and is maintained through the categories that follow, dealing with the nature of this quest, the structure of the ego, the experiences of mysticism, the study of philosophy, and the understanding of mentalism. All these work toward weakening our identification with the ego and strengthening our awareness of the Overself.

The practices and attitudes presented in Advanced Contemplation deepen this contact with the Overself until the ego must surrender to its guidance both in daily life and in meditation. Here we begin the quest anew, with a direct comprehension of the goal for the first time. At last we come to know that nothing else matters, that there is nothing outside the quest. Up to this point the quest may be an intermittent affair, a confusing journey through the misconceptions and misdirections of the ego; hereafter, the student moves in light along the mysterious path of spiritual attainment. This is because the quester is no longer primarily concerned with battling the ego; the focus is now on living always in the presence of the Overself.

Advanced Contemplation explores the nature of this redirection of attention from ego to Overself and shows us how it can be done. Then The Peace Within You shows us how to live inside the quest, inside the stillness of the Overself, once this transition has occurred.

As we look through the topics in The Notebooks, we can see that P.B. considers the quest as ascending through three levels: the physical, the subtle, and the mental. As P.B. examines each level, he alternates between objective understanding and subjective awareness. For example, in The Sensitives (category sixteen) P.B. acquaints us with the misconceptions and ignorance about the psychic realm. This acquaintance prepares the way for The Reverential Life (category eighteen), where we turn our hearts toward the image of the Overself in the subtle plane of interior feeling. P.B. repeats this pattern in categories nineteen through twenty-two: First he defines the characteristics with which mind imbues experience and the nature of the mind itself (nineteen through twenty-one); then he lifts our awareness beyond the mental plane into the intuitive awareness of the Overself (twenty-two).

This pattern of alternating objective and subjective perspectives reaches its conclusion in Advanced Contemplation. On a first reading, this category may appear to have two sections: the first five chapters, which include the definitions of the Short Path and its combination with the Long Path, and the last three chapters, which describe various techniques for advanced meditation, including contemplations of the Void. However, a closer reading will show that this category is a whole.

The difference between the extroverted state of mind, treated in the first five chapters, and the introverted mind, treated in the last three chapters, must become very slight if this stage of the quest is to be successful. In fact, in the next category, The Peace within You, this difference vanishes as completely as it can. This blending of the objective and subjective perspectives is a central point for the interplay of these two categories, which are bound together as one volume in the printed edition. In the opening chapter of Advanced Contemplation, P.B. tells us to begin and end with the goal, to turn 180 degrees around — not away from the ego, but toward the Overself. He tells us to face the Overself always, and in all ways: to orient our daily life and activities towards the achievement of its presence, and to devote our meditations not to its symbols or signs but to itself alone. This single-minded focus on the transcendent Overself naturally draws the extroverted mind and the introverted mind more closely together, since the primary content of either one is now the same. When P.B. describes the Void as a contemplative state, he makes it clear that no sort of subject or object can exist in that state, and that the stillness it generates cannot be accurately described in either context alone.

Another point P.B. makes in Advanced Contemplation is that the Short Path gets its name neither from its speed of attainment nor from its ease of accomplishment, but from the directness of its approach to the quest. Like a solitary ascent of a challenging cliff-face, the Short Path keenly focuses the mind on the demands of spiritual development. This approach is a necessary stage of the quest, and one whose dangers are real if we make the assault unready and unaware. The nature of these risks and remedies is discussed in the second and third chapters. Having made the challenge and the warnings clear, in chapter four P.B. describes exactly how we can make the changeover to the Short Path. Then, in chapter five, P.B. adds his wonderful sense of balance to the picture, pointing out the place of the Long Path's milder approach — as first separate, then interwoven with, and finally combining with the Short Path to become the philosopher's way of life. So P.B. begins by presenting the Short Path as a challenge to the quester, but concludes by stating that the Short Path, when balanced by the Long Path, becomes the "way'' of living in the radiant presence of the Overself.

The chapters of Advanced Contemplation are arranged as a development from simple to more advanced stages of practice. The fundamental stages, however, are only briefly described here, as they have been fully discussed in earlier categories. We recommend that readers review Practices for the Quest (category two) and Meditation (category four) as a part of studying Advanced Contemplation. Category two gives a full consideration of the Long Path; it may be helpful to read chapters one and nine there before reading chapters four and five of the present category. It is likewise especially important to review the section titled "Levels of Absorption'' in the first chapter of Meditation (category four) before reading the meditation exercises and experiences in chapters six through eight of Advanced Contemplation. That section defines and describes all the stages of meditation, right up through advanced contemplation, and gives some indication of how to recognize them. Readers who have already studied Meditation will notice that we have repeated nine paras from that section as a reference guide to P.B.'s description and definition of the various stages of meditation and contemplation; see paras 52–60 in chapter seven, "Contemplative Stillness," below.

We should also mention that chapter three, "The Dark Night of the Soul,'' is not a topic P.B. originally assigned to this category. These paras were originally scattered throughout the various categories. We felt, however, that having all this material in one place would be useful to individuals confronted with this difficult experience, and that the subject — while not exactly belonging in Advanced Contemplation — does depend upon ideas and practices first described here. This artificial gathering of a topic into one place by the editors is very rare in the Notebooks series — almost all topics were originally given their placement into specific categories by P.B.

Editorial conventions here are the same as stated in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that it also appears in Perspectives, the introductory volume to this series.

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category twenty-four, The Peace within You

The chapter titles of The Peace within You summarize nearly all that can be said about this section: The Search for Happiness; Be Calm; Practise Detachment; and Seek the Deeper Stillness. Here we meet the Great Silence of the Overself and the Peace that motivates our desire for happiness — the same Peace that we ultimately find underlying even our greatest sorrows. The difference between categories twenty-three and twenty-four is that the quester is seeking the stillness of the Overself in every part of life in Advanced Contemplation, while in The Peace within You the quester is learning to live inside the stillness. Appropriately, the practices in The Peace within You are designed to create a way of living that doesn't disturb one's awareness of the presence of the Overself.

The difference between these two stages can be seen by comparing the paras on the Witness exercise in chapter six of Advanced Contemplation to the paras titled "Becoming the Witness'' in chapter three of The Peace within You. In the first group, the quester is shown how to bring about the Witness attitude; the second group shows how to apply this attitude in the practice of detachment.

The Peace within You provides a sort of contemplative pause between the revolutionary enterprise of the Short Path and the final challenge of the "Enlightenment which Stays" that emerges in category twenty-five. Even though there is but a short distance in print between these two stages, the length of time between them may prove to be quite long. This is because much of the quester's growth now occurs in silence, and really can't be expressed in thought. So it is fitting that this volume ends with the section titled "The Great Silence.''

Editorial conventions here are the same as stated in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that it also appears in Perspectives, the introductory volume to this series.

Excerpts from Notebooks category twenty-three, Advanced Contemplation

PREFATORY

EVOLUTION IS only an idea within the mind, hence it has the value of something imagined. The reality is that one has never left the heavenly being, but ignorance prevents him from realizing this. To get rid of this ignorance, he must sharpen the mind by constant effort, tranquillize it by meditation, and guide it through the help of a teacher.

WHATEVER PATH a man starts with, he must at the end of it come to the entrance of this path — the destruction of the illusion of the ego and giving up identification with it.

From chapter 1: ENTERING THE SHORT PATH

Begin and end with the goal itself

1

This notion that we must wait and wait while we slowly progress out of enslavement into liberation, out of ignorance into knowledge, out of the present limitations into a future union with the Divine, is only true if we let it be so. But we need not. We can shift our identification from the ego to the Overself in our habitual thinking, in our daily reactions and attitudes, in our response to events and the world. We have thought our way into this unsatisfactory state; we can unthink our way out of it. By incessantly remembering what we really are, here and now at this very moment, we set ourselves free. Why wait for what already is?

2

All other approaches to the goal depend on a dualistic principle, which puts them on a lower plane. But the Short Path is nondual: it begins and ends with the goal itself; its nature is direct and its working is immediate.

3

Consciousness appearing as the person seeks itself. This is its quest. But when it learns and comprehends that it is itself the object of that quest, the person stops not only seeking outside himself but even engaging in the quest itself. Henceforth he lets himself be moved by the Overself's flow.

4

All these substitutes for the truth may appear to be useful stepping-stones to it but in fact they keep him from it, for there is no end to the number of steps he will be able to take since there is no end to the number of ways the human mind can spin out its ideas and fancies. Unless he begins with the end first, he will get lost on the way to it.

From chapter 5: BALANCING THE PATHS

Their contrast and comparison\

2

Most people who start the short path have usually had a glimpse of the Overself, because otherwise they find it too difficult to understand what the short path is about. The long path, through its studies and practices, is the period of preparation for the advanced quest. It is called the long path because there is much work to be done on it and much development of character and emotions to go through. After some measure of this preparation the aspirants enter the short path to complete this work. This takes a comparatively much shorter time and, as it has the possibility of yielding the full self-enlightenment at any moment, it ends suddenly. What they are trying to do on the long path continues by itself once they have entered fully on the short path. On the long path they are concerned with the personal ego and as a result give the negative thoughts their attention. On the short path they refuse to accept these negatives and instead look to the Overself. Thus the struggles will disappear. This change of attitude is called "voiding" them. The moment such negative ideas and feelings appear, then instead of using the long path method of concentrating on the opposite kind of thought, such as calmness instead of anger, the short path way simply drops the negative idea into the Void, the Nothingness, and forgets it. Now such a change can only be brought about by doing it quickly and firmly and turning to the Overself. Constant remembrance of the Overself has to be done all the way through the short path. The long path works on the ego; but the short path uses the result of that work, which prepared them to come into communion with the Overself and become receptive to its presence, which includes its grace. In order to understand the short path, it might be helpful to compare it to the long path which consists of a series of exercises and efforts which gradually develops concentration and character and knowledge. But the long path does not lead to the goal. On the long path you often measure your own progress. It is an endless path because there will always be new circumstances which bring new temptations and trials and confront the aspirant with new challenges. No matter how spiritual the ego becomes it does not enter the whitest light, but remains in the greyish light. On the long path you must deal with the urges of interference arising from the lower self and the negativity which enters from the surrounding environment. But the efforts on the long path will at last invoke the grace, which opens the perspective of the short path.

The short path is not an exercise but an inner standpoint to invoke, a state of consciousness where one comes closer or finds peace in the Overself. There are, however, two exercises which can be of help to lead to the short path, but they have quite a different character than the exercises on the long path. The short path takes less time because the aspirant turns around and faces the goal directly. The short path means that you begin to try to remember to live in the rarefied atmosphere of the Overself instead of worrying about the ego and measuring its spiritual development. You learn to trust more and more in the Higher Power. On the short path you ignore negativity and turn around 180 degrees, from the ego to the Overself. The visitations of the Overself are heralded through devotional feeling, but also through intuitive thought and action. Often the two paths can be treaded simultaneously, but not necessarily equally.

Often the aspirant is not ready to start these two exercises until after one or several glimpses of the Overself.

The "remembrance exercise" consists of trying to recall the glimpse of the Overself, not only during the set meditation periods but also in each moment during the whole working span of the day - in the same way as a mother who has lost her child can not let go of the thought of it no matter what she is doing outwardly, or as a lover who constantly holds the vivid image of the beloved in the back of his mind. In a similar way, you keep the memory of the Overself alive during this exercise and let it shine in the background while you go about your daily work. But the spirit of the exercise is not to be lost. It must not be mechanical and cold. The time may come later when the remembrance will cease as a consciously and deliberately willed exercise and pass by itself into a state which will be maintained without the help of the ego's will.

The remembrance is a necessary preparation for the second exercise, in which you try to obtain an immediate identification with the Overself. Just as an actor identifies with the role he plays on the stage, you act think and live during the daily life "as if" you were the Overself. This exercise is not merely intellectual but also includes feeling and intuitive action. It is an act of creative imagination in which by turning directly to playing the part of the Overself you make it possible for its grace to come more and more into your life.

From chapter 7: CONTEMPLATIVE STILLNESS

233

A point is reached where the seeker must stop making a thought of the Overself, or he will defeat himself and ensure inability to go beyond the intellect into the Overself. At this point he is required to enter the Stillness.

314

The fear of annihilation which comes to a number of persons who meditate deeply enough, and which forces them to withdraw themselves from the practice for that session, is justifiable. There is an experience which seems to be equivalent to self-obliteration. Nevertheless it is not the end of existence, for it is followed by an entry into the beautiful white light, bringing an immense feeling of space and goodwill, of harmony and liberation from all that is low, of peace and compassion. The whole experience is so vivid, so real, so convincing — all through from beginning to end — that whether or not it recurs, it will remain forever in his memory. It has also a strange power when recalled years afterwards in moments of trouble and distress to provide inner help and support.

315

This transparent light-world is the source of creation, the cosmic birthplace, the home of dazzling primal energy. Galaxies, universes, suns, and planets come forth from here. The revelatory, blissful vision of God's Form may happen only once in a lifetime. Beyond it all is God without Form — the still void.

322

The novice must cautiously feel his way back from the divine centre at the end of his period of meditation to the plane of normal activity. This descent or return must be carefully negotiated. If he is not careful he may easily and needlessly lose the fruit of his attainment. An exercise to accomplish this, to bring the meditator slowly back to earth and to prepare him for the external life of inspired activity, is the following one: very slowly opening and shutting eyelids several times. Those moments immediately following cessation of meditation are equally as important as the period preceding. They are of crucial importance in fact. For in those few minutes he may have lost much of what he gained during the whole period. Hold the state attained as gently and preciously as you would hold a baby. Hold to the centre and do not stray from it. Such a state the yogis call sahaja samadhi: despite all moving about there is non-action, for the heart is free.

Excerpts from Notebooks category twenty-four, The Peace within You

PREFATORY

For the person who is not a complete beginner, who has attained a modest proficiency in the inner life, there is no real contradiction between the inner and the outer life. The one kind of existence will be inspired by the other. Neither despising the world nor becoming lost in it, he moves in poised safety through it. Outwardly we live and have to live in the very midst of cruel struggle and grievous conflict, for we share the planet's karma; but inwardly we can live by striking contrast in an intense stillness, a consecrated peace, a sublime security. The central stillness is always there, whether we are absorbed in bustling activity or not. Hence a part of this training consists in becoming conscious of its presence. Indeed only by bringing the mystical realization into the active life of the wakeful world can it attain its own fullness. The peaceful state must not only be attained during meditation, but also sustained during action.

From chapter 1: THE SEARCH FOR HAPPINESS

The heart of joy

74

If you investigate the matter deeply enough and widely enough, you will find that happiness eludes nearly all men despite the fact that they are forever seeking it. The fortunate and successful few are those who have stopped seeking with the ego alone and allow the search to be directed inwardly by the higher self. They alone can find a happiness unblemished by defects or deficiencies, a Supreme Good which is not a further source of pain and sorrow but an endless source of satisfaction and peace.(P)

75

Pleasure is satisfaction derived from the things and persons outside us. Happiness is satisfaction derived from the core of deepest being inside us. Because we get our pleasures through the five senses, they are more exciting and are sharper, more vivid, than the diffused self-induced thoughts and feelings which bring us happiness. In short, pleasure is of the body whereas something quite immaterial and impalpable is the source of our happiness. This is not to say that all pleasures are to be ascetically rejected, but that whereas we are helplessly dependent for them on some object or some person, we are dependent only on ourselves for happiness.(P)

From chapter 4: SEEK THE DEEPER STILLNESS

1

When the personal ego's thoughts and desires are stripped off, we behold ourselves as we were in the first state and as we shall be in the final one. We are then the Overself alone, in its Godlike solitude and stillness.(P)

2

One feels gathered into the depths of the silence, enfolded by it and then, hidden within it, intuits the mysterious inexplicable invisible and higher power which must remain forever nameless.

3

A life with this infinite stillness as its background and centre seems as remote from the common clay of everyday human beings, and especially from their urban infatuation with noise and movement, as the asteroids.

4

This stillness is the godlike part of every human being. In failing to look for it, he fails to make the most of his possibilities. If, looking, he misses it on the way, this happens because it is a vacuity: there is simply nothing there! That means no things, not even mental things, that is, thoughts.(P)

5

The spirit (Brahman) is NOT the stillness, but is found by humans who are in the precondition of stillness. The latter is their human reaction to Brahman's presence coming into their field of awareness.(P)

6

That beautiful state wherein the mind recognizes itself for what it is, wherein all activity is stilled except that of awareness alone, and even then it is an awareness without an object — this is the heart of the experience.(P)

In his own words:

“Writing, which is an exercise of the intellect to some, is an act of worship to me. I rise from my desk in the same mood as that in which I leave an hour of prayer in an old cathedral, or of meditation in a little wood . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 143

“P.B. as a private person does not count. There are hundreds of millions of such persons anyway. What is one man and his quest? P.B.’s personal experiences and views are not of any particular importance or special consequence. What happens to the individual man named P.B. is a matter of no account to anyone except himself. But what happens to the hundreds of thousands of spiritual seekers today who are following the same path that he pioneered is a serious matter and calls for prolonged consideration. Surely the hundreds of thousands of Western seekers who stand behind him and whom indeed, in one sense, he represents, do count. P.B. as a symbol of the scattered group of Western truth-seekers who, by following his writings so increasingly and so eagerly, virtually follow him also, does count. He personifies their aspirations, their repulsion from materialism and attraction toward mysticism, their interest in Oriental wisdom and their shepherdless state. As a symbol of this Western movement of thought, he is vastly greater than himself. In his mind and person the historic need for a new grasp of the contemporary spiritual problem found a plain-speaking voice . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 145

Learn more about Paul Brunton through articles at the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation web site

Electronic versions of this book are available from all major (Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, etc.) and most smaller ebook vendors. Please don't try to order ebooks directly from us, as we are not yet able to deliver anything to you in a preferred electronic format.

To see all our Paul Brunton titles, scroll down to The Complete Paul Brunton Opus below.

Click here to see or order the complete set of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

About Paul Brunton

Paul Brunton helps us hear the melody behind the medley of today's "spiritual marketplace." His late writings raise the bar for what we can expect of spiritual teachings and teachers, and what we can do for ourselves. Born in London in 1898, he soon became a leading pioneer of much of what we now take for granted. He traveled widely throughout the world (long before it was fashionable) to meet living masters of various traditions with whom he then lived and studied. His eleven early books from 1934–1952 shared much of what he learned, and helped set the stage for dramatic east-west exchanges of the late 20th century. Paul Brunton left more than 10,000 pages of enormously helpful new work in notebooks he reserved for posthumous publication, much of which is now available as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. See "The Complete Paul Brunton Opus" in blue below to see his many works available on this site. You can also search on Paul Brunton in the search bar to browse the selections, or click on a link below for specific connections.

Click here for an article about Paul Brunton.

Click here for The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

To access small theme-based books compiled from Paul Brunton's writings, scroll down to Derived from the Notebooks below.

To access Paul Brunton's early writings, published from 1934–1952, scroll down to Paul Brunton's Early Works below.

To access commentaries on Paul Brunton and his work by his leading student, Anthony Damiani, as well as other writings about Paul Brunton and/or his work, scroll down to Commentaries and Reflections on Paul Brunton and His Work below.

The Complete Paul Brunton Opus:

Paul Brunton's most mature work, in the order he specified for posthumous publication.

Smaller books on popular/timely themes, developed from the Notebooks and published posthumously.

Paul Brunton's works published during his lifetime from 1934-1952

Commentaries/Reflections by other authors on Paul Brunton or his works.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)