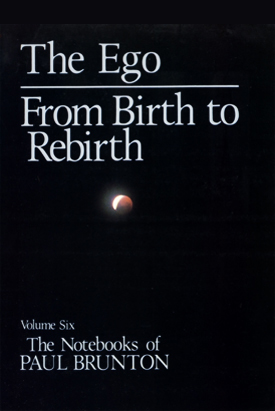

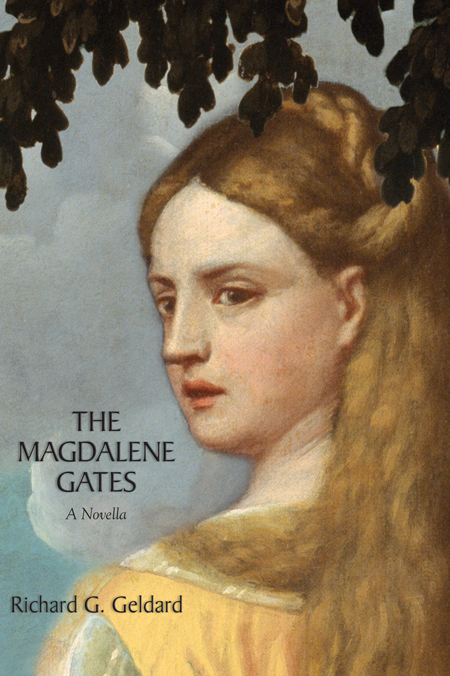

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton volume 6

The Ego

From Birth to Rebirth By Paul Brunton

Retail/cover price: $18.95

Our price : $15.16

(You save $3.79!)

About this book:

The Notebooks of Paul Brunton volume 6

The Ego

From Birth to Rebirth

by Paul Brunton

The Ego is a unique, unprecedented, enormously useful resource for discovering / developing spiritual integrity.

From Birth to Rebirth explores the role of death in the cycle of life . . .

Subjects: Personal Transformation, Spirituality, Psychology

5.75 x 8.5, softcover

(hardcover is available)

320 pages

ISBN 10: 0-943914-25-6

ISBN 13: 978-0-943914-25-1

Book Details

Part 1, The Ego, is one of Paul Brunton's greatest and most unique gifts to the literature of realization—a truly earth-shaking piece of work for serious spiritual seekers. With no holds barred, it exposes, at an existential level, the most fundamental problems that obstruct achieving a life of unfailing self-integrity.

Part 2, From Birth to Rebirth, shows the role of death in the ongoing cycle of life, clarifies beliefs about reincarnation, and explores the creative relationships between fate, destiny, and free will.

Category Eight: THE EGO

INTRODUCTION

1. WHAT AM I?

Egoself and Overself

Body and consciousness

I-sense and memory

Ego as limitation

Ego as presence of higher

Two views of individuality

Perfection through surrender

Ego subordinated, not destroyed

Ego after illumination

Reincarnation

2. I-THOUGHT

I-sense and I-thought

Ego exists, as series of thoughts

Subject-object

3. PSYCHE

Ego as knot in psyche

The "subconscious"

Trickery, cunning of ego

Defense mechanisms

Self-idolatry

Egoism, egocentricity

4. DETACHING FROM THE EGO

Its importance

Why most people won't do it

As genuine spiritual path

Surrender is necessary

Its difficulty

Ego corrupts spiritual aspiration

Humility is needed

Longing for freedom from ego

Knowledge is needed

Tracing ego to its source

"Dissolution" of ego

Grace is needed

Who is seeking?

Results of dethroning ego

Category Nine: FROM BIRTH TO REBIRTH

INTRODUCTION

1. DEATH, DYING, AND IMMORTALITY

Continuity, transition, and transformation

The event of death

The aftermath of death

2. REBIRTH AND REINCARNATION

The influence of past tendencies

Reincarnation and Mentalism

Beliefs about reincarnation

Reincarnation and the Overself

3. LAWS AND PATTERNS OF EXPERIENCE

Defining karma, fate, and destiny

Karma's role in human development

Destiny turns the wheel

Astrology, fate, and free will

Karma, free will, and the Overself

4. FREE WILL, RESPONSIBILITY, AND THE WORLD-IDEA

The limitations of free will

The freedom we have to evolve

Human will in the World-Idea

“. . . a veritable treasure-trove of philosophic-spiritual wisdom.” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

“. . . sensible and compelling. His work can stand beside that of such East-West bridges as Merton, Huxley, Suzuki, Watts, and Radhakrishnan. It should appeal to anyone concerned personally and academically with issues of spirituality.” —Choice

“Vigorous, clear-minded and independent . . . a synthesis of Eastern mysticism and Western rationality. . . A rich volume.” —Library Journal

“. . . a great gift to us Westerners who are seeking the spiritual.” —Charles T. Tart

“A person of rare intelligence. . . thoroughly alive, and whole in the most significant, 'holy' sense of the word.” —Yoga Journal

For more reviews of the Notebooks series, click here

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category eight, The Ego

The Ego is a unique and unprecedented contribution to the literature of self-realization. It goes to the root of the most fundamental and immediate problem facing those who would live with unfailing self-integrity. It confronts this problem at an existential, rather than merely a psychological, level. As a result, the very reading of this material becomes a profitable spiritual exercise.

To make best use of the opportunity for lasting breakthrough which this section offers, the reader should recognize from the outset that this material abounds in information that the ego does not want its captive to hear. Further, every effort should be made to avoid premature judgements based on associations with other systems, especially psychological systems, where the word "ego" is used differently than here. Relentlessly probing and exploring, this section covers a broad range; its content is not readily reducible to a neat, tidy structure within which the ego-mind can feel comfortable. From high praise at one extreme to utter denigration at the other, it offers many viewpoints, explores many facets of the complex ego's origin, nature, and destiny. In its entirety, it leads masterfully beyond ordinary intellectualizing and into the intuitive realm of paradox where kernels of deep spiritual realization are lodged.

In structuring this material for publication, we found that any linear structure we came up with had serious limitations. The integrated wholeness of the insight behind this material demands being seen intuitively if it is to be seen clearly at all. The best approach we have seen is the one used by Anthony Damiani, a close and lifelong student of P.B. When first studying this section, he put individual paras on separate cards. He would read each one, then shuffle the "deck" randomly and read them all again. Reading in this way, he said, forced his mind to seek out and dwell in the insight behind the individual paras rather than in the associations his ego would construct between them.

What is true in general for reading The Notebooks, then, is especially true for reading the material in The Ego. The natural associative activity of the lower mind—its tendency to look for and make connections between independent thoughts—should be resisted, even suspended if possible, for the first few readings of the entire material. Individual paras should be meditated upon in and of themselves. The reader should compel his or her ego to let what is being said be heard.

Only after the entire range of viewpoints, the 360-degree perspective, has been assimilated will the radically transformative truths underlying surface contradictions gradually seep into the psyche and explain themselves. The reader's task for the present should be to savor each para, to take in each one as fully as possible. The inability to see readily how they can all fit together should not become a cause of anxious frustration. Careful study of the material will lead eventually to an integration, through Grace, of understanding at a deeper, now unconscious, level. In the meantime, we hope that the tentative structure we have provided for the purposes of publication in book form will at least not interfere with the working of the reader's intuition.

Editorial conventions are the same here as stated in introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that the para also appears in Perspectives, the introductory survey volume to this series.

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category nine, From Birth to Rebirth

From Birth to Rebirth focuses on two great problems of philosophy—our death and our destiny. These issues are especially relevant to our further understanding of the ego, as the ego is what recurrently is born and dies, and our conscious life in/as the ego is what the laws of recompense and free will affect.

Chapter one discusses the event of death, in our own lives and in the lives of others. It offers practical advice on helpful attitudes towards death and on how we can approach the experience of dying. It examines after-death states, our limited contact with those already dead, and our permanent connection to the immortal Overself now, and then.

In Chapter two, P.B. reflects on the cycle of life and death, through a consideration of teachings on reincarnation. Here he explores how one's own past reappears in present character, is active in the conditions of birth, and is a significant factor in all subsequent experiences. Many beliefs and superstitions surround this ancient doctrine and its significance in the journey toward wisdom. P.B. sorts through various historical modifications with his usual rational perspective to provide us with a clear, if somewhat complex, treatment of the subject.

Chapter three is a collection of P.B.'s remarks on karma, fate, destiny, and free will. Several paras in its first section indicate that P.B. considered these first three terms as interrelated but distinct forces or cosmic laws involved in the shaping of our lives and egos. The chapter's emphasis is on our experience of these laws: how to recognize their presence, and how our interaction with them may—or may not—change our circumstances. In this context, P.B. introduces a philosophic consideration of astrology, showing what it teaches us, how it can be used to help us understand our destiny, and how it can be misused. The chapter ends with a selection of paras examining free will from the perspective of destiny.

The final chapter deals with the question of free will: its limitations and opportunities, and our responsibility to use it wisely. We see here that death and rebirth, karma, fate, destiny, and limited free will are powers that shape the ego and bind its development to the larger evolution of the World-Idea. The section ends with paras in which P.B. reminds us of our heritage in the Overself, wherein lies freedom, refuge, guidance, and our true home.

Editorial conventions are the same here as stated in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that it also appears in Perspectives, the introductory survey volume to this series.

Excerpts from Notebooks category eight, The Ego

Prefatory:

The danger of most pseudo-spiritual paths is that they stimulate the ego, whereas the authentic path will suffocate it.

The best measuring-stick for progress is, in earlier stages, the degree of disappearance of the ego's rule and, in later ones, the degree of disappearance of the ego itself.

From chapter 1: WHAT AM I?

Egoself and Overself

1

That element in his consciousness which enables him to understand that he exists, which causes him to pronounce the words, "I Am," is the spiritual element, here called Overself. It is really his basic self for the three activities of thinking feeling and willing are derived from it, are ripples spreading out of it, are attributes and functions which belong to it. But as we ordinarily think feel and act, these activities do not express the Overself because they are under the control of a different entity, the personal ego.

2

The source of wisdom and power, of love and beauty, is within ourselves, but not within our egos. It is within our consciousness. Indeed, its presence provides us with a conscious contrast which enables us to speak of the ego as if it were something different and apart: it is the true Self whereas the ego is only an illusion of the mind.

3

Is it true that most men suffer from mistaken identity? That they are totally ignorant of the beautiful and virtuous, the aspirational and intuitive nature which is their higher self? The apathy which allows them to accept their lesser nature, their commonplace little self, must be found out for what it is.

4

Since the person a man is most interested in is himself, why not get to know himself as he really is, not merely as he appears to be?

5

Within every human entity there is a silent pull from within toward its centre, the real self. But alongside of this there is a stronger pull from without toward its instruments—the body's senses, the intellect, and the feelings—the false self. The entity is compelled to divide itself, its life and attention, between these two opposites, involuntarily through waking and sleeping, voluntarily through the ego surrendered to the Overself.

6

What is the ego but the Overself surrounded with barriers, conditioned by its instruments — the body, the feelings, and the intellect — and forgetful of its own nature?

7

The ego self is the creature born out of man's own doing and thinking, slowly changing and growing. The Overself is the image of God, perfect, finished, and changeless. What he has to do, if he is to fulfil himself, is to let the one shine through the other.(P)

8

Think! What does the "I" stand for? This single and simple letter is filled with unutterable mystery. For apart from the infinite void in which it is born and to which it must return, it has no meaning. The Eternal is its hidden core and content.

9

The ego is after all only an idea. It derives its seeming actuality from a higher source. If we make the inner effort to search for its origin we shall eventually find the Mind in which this idea originated. That mind is the Overself. This search is the Quest. The self-separation of the idea from the mind which makes its existence possible, is egoism.

10

What he takes to be his true identity is only a dream that separates him from it. He has become a curious creature which eagerly accepts the confining darkness of the ego's

life and turns its back on the blazing light of the soul's life.

11

Once this question — what am I? — is answered, there are no other questions. In the light of its dazzling answer, he knows how to handle all his problems.

12

The self which gives him a personal consciousness is not his truest self.

13

What does a man regard as himself? It is the conscious centre of all that he thinks and experiences, feels and does.

From chapter 2: I-THOUGHT

I-sense and I-thought

1

What we commonly think of as constituting the "I" is an idea which changes from year to year. This is the personal "I." But what we feel most intimately as being always present in all these different ideas of the "I," that is, the sense of being, of existence, never changes at all. It is this which is our true enduring "I."

2

If past and future are now only ideas, the present must be idea, too. So runs the mentalist explanation. But this can and should be carried still farther. If the experiencer of past and future is (because he is part of them) now an idea, then the experiencer of the present (and in the present) must be idea, too. As anything else than idea, he was (and is) only a supposition, which is the same as saying that the ego is only an apparent entity and has no more reality (or less) than any thought has.

3

Everything remembered is a thought in consciousness. This not only applies to objects, events, and places. It also applies to persons, including oneself, he who is remembered, the "I" that I was. This means that my own personality, what I call myself, was a thought in the past, however strong and however persistent. But the past was once the present. Therefore I am not less a thought now. The question arises what did I have then which I still have now, unchanged, exactly the same. It cannot be "I" as the person, for that is different in some way each time. It is, and can only be, "I" as Consciousness.

4

The "I"-consciousness is the essence of the "Me," the seeming self.

5

All that a man really owns is his "I." Everything else can be taken from him in a moment - by death or destiny, by his own foolishness or other people's malice. But no event and no person can rob him of his capacity to think the "I."

6

With the body, the thoughts, and the emotions, the ego seems to complete itself as an entity. But where do we get this feeling of "I" from? There is only one way to know the answer to this question: the way of meditation. This burrows beneath the three mentioned components and penetrates into the residue, which is found to be nothing in particular, only the sense of Be-ing. And this is the real source of the "I" notion, the self-feeling. Alas! the source does not ordinarily reveal itself, so we live in its projection, the ego, alone. We are content to be little, when we could be great.

7

That which claims to be the "I" turns out to be only a part of it, the lesser part, and not the real "I" at all. It is a complex of thoughts.

8

When the "I" is thought to be the body, appearance has replaced reality.

9

This feeling of I-ness may be associated with the body, emotions, and thoughts — whose totality is the personal ego — or shifted in deep meditation to the rootless root of being, which is the Overself; or, it may be associated with both, when one will be the reality and the other a shadow of reality.

10

The idea of a self first enters consciousness when a child identifies itself with bodily feelings, and later when it adds emotional feelings. The idea extends itself still later, with logical thoughts and, lastly, completes itself with the discovery of individuality.

11

Descartes' reference in his statement, "I think therefore I am," is simply to himself as a person, a self limited to body emotion and thought, that is, to ordinary experience and nothing higher or deeper than that, a being whose consciousness is unexamined and unexplored.

12

Ego means the consciousness of self.

Excerpts from Notebooks category 9, From Birth to Rebirth

From chapter 1: DEATH, DYING, AND IMMORTALITY

Continuity, transition, and transformation

1

Life-in-Itself is infinite and unchanging, but there is an end to the kind of experience undergone by the living entity in its finite human phase.

2

Just as sound goes back into silence but may emerge again at some later time, so this little self goes back into the greater being from which it too may emerge again at another time.

3

We worry ourselves through the days of an existence which is itself but a day. A profound sadness falls on the heart when it realizes the transient nature of all worldly things and all human being.

4

If decay and disintegration were not present at some stage, if our life spans were extended to say double their present length, then the old would outnumber all other sections of society. Stasis would overwhelm culture because the bodily slowdown would reflect itself mentally. The World-Mind had a better idea.

5

Human life steadily and unfailingly burns away like the candle in a man's hands.

6

Individuated life is forever doomed to die whereas the ALL which receives the dying can itself never die.

7

Even stars must die one day, more violently and dramatically than most human beings, for even they come under the law that whatever had a beginning must also have an ending.

8

We hear of other people dying and make suitable comment, but we do not feel that the time is coming when this fate will be ours too.

9

It is not so much because death deprives man of his possessions and relations that he dreads it, as the possibility that it deprives him of his consciousness - that is, his self, his ego.

10

Those who deplore, lament, or wail at the inevitability of death are viewing it in a very narrow, short-sighted way. The more mature ought to be thankful that we humans are not condemned to remain forever confined to a single body: this would indeed become a source of anxiety, if not of hopelessness.

11

Whether this bundle of personal desires and memories which is the ego, but which some of the pious call their soul, will be annihilated at death or perpetuated, is not an anxiety for the philosopher.

12

The more they enjoy the world the more they suffer when they leave it - unless they have learnt to put detachment behind the enjoyment.

13

No force can be destroyed; it can only be rechannelled. Life is a force; death is its rechannelling.

From chapter 4: FREE WILL, RESPONSIBILITY, AND THE WORLD-IDEA

The limitations of free will

1

The events of our future remain in a fluid state until a certain time. We have the free will to modify them during that period, although it is never an absolute freedom.

2

Inevitably and ultimately, will must prove stronger than fate because it is our own past will which created our present fate.

3

The awareness that they are weak and faulty makes some persons regard free will, not as the boon it is generally supposed to be, but as a danger. Saint Therese of Lisieux even asked God to take it away because it frightened her.

4

He who asserts that he is free to do what he wishes to do would more correctly state his situation by confessing that he is enslaved by his ego and goes up or down as its emotional see-saw moves.

5

It is not only the karma of a man which may oppose itself to his free choice and free will; there are also the possibilities of opposition by human institutions and organizations, natural calamities and catastrophes, genetic heredity and racial predisposition.

6

If a man's will were really free, he would have to think of using it before he actually did so, and then again to think of thinking of using it, and so on in an endless series. Since this situation never occurs, are we to believe that his will is never free? This is a question that no man can answer for it ought never to be put.

7

Even the man who believes that he possesses the attribute of free will finds himself forced to accept certain events just like others who do not believe they possess it.

8

Too many persons claim a freedom to choose and to will who in reality have only the very opposite — a captivity to their desires. These desires respond like a machine to the conditions which surround them and delude them into the belief that they are deliberately choosing from among those conditions. The moods and emotions of these persons are changed by every change of outer circumstance, provoked favourably or unfavourably by the nature of each change. Where is the freedom in this? Does it not rather show dependence?

9

Most human beings are so automatic and predictable in their habitual reactions that they are like machines. And where is the freedom of a machine? They are really helpless creatures, devoid of free will. Despite this, they do possess a latent freedom, even though they are not evolved enough to claim it.

10

A man imprisoned in the circle of his own ego still imagines he has free will!

In his own words:

“Writing, which is an exercise of the intellect to some, is an act of worship to me. I rise from my desk in the same mood as that in which I leave an hour of prayer in an old cathedral, or of meditation in a little wood . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 143

“P.B. as a private person does not count. There are hundreds of millions of such persons anyway. What is one man and his quest? P.B.’s personal experiences and views are not of any particular importance or special consequence. What happens to the individual man named P.B. is a matter of no account to anyone except himself. But what happens to the hundreds of thousands of spiritual seekers today who are following the same path that he pioneered is a serious matter and calls for prolonged consideration. Surely the hundreds of thousands of Western seekers who stand behind him and whom indeed, in one sense, he represents, do count. P.B. as a symbol of the scattered group of Western truth-seekers who, by following his writings so increasingly and so eagerly, virtually follow him also, does count. He personifies their aspirations, their repulsion from materialism and attraction toward mysticism, their interest in Oriental wisdom and their shepherdless state. As a symbol of this Western movement of thought, he is vastly greater than himself. In his mind and person the historic need for a new grasp of the contemporary spiritual problem found a plain-speaking voice . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 145

Learn more about Paul Brunton through articles at the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation web site

Electronic versions of this book are available from all major (Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, etc.) and most smaller ebook vendors. Please don't try to order ebooks directly from us, as we are not yet able to deliver anything to you in a preferred electronic format.

To see all our Paul Brunton titles, scroll down to The Complete Paul Brunton Opus below.

To see and/or order individual volumes in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, hover your mouse over the specific cover in the Notebooks section of Complete Paul Brunton Opus below, then click on Details in the box that appears within it.

Click here to see or order the complete set of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

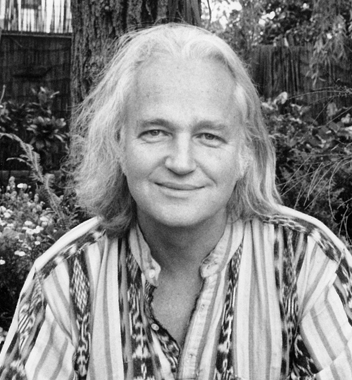

Click here to see Standing in Your Own Way, Anthony Damiani's inspiring commentary on and development of the material in this volume.

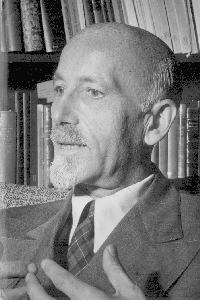

Paul Brunton helps us hear the melody behind the medley of today's "spiritual marketplace." His late writings raise the bar for what we can expect of spiritual teachings and teachers, and what we can do for ourselves. Born in London in 1898, he soon became a leading pioneer of much of what we now take for granted. He traveled widely throughout the world (long before it was fashionable) to meet living masters of various traditions with whom he then lived and studied. His eleven early books from 1934–1952 shared much of what he learned, and helped set the stage for dramatic east-west exchanges of the late 20th century. Paul Brunton left more than 10,000 pages of enormously helpful new work in notebooks he reserved for posthumous publication, much of which is now available as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. See "The Complete Paul Brunton Opus" in blue below to see his many works available on this site. You can also search on Paul Brunton in the search bar to browse the selections, or click on a link below for specific connections.

Click here for an article about Paul Brunton.

Click here for The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

To access small theme-based books compiled from Paul Brunton's writings, scroll down to Derived from the Notebooks below.

To access Paul Brunton's early writings, published from 1934–1952, scroll down to Paul Brunton's Early Works below.

To access commentaries on Paul Brunton and his work by his leading student, Anthony Damiani, as well as other writings about Paul Brunton and/or his work, scroll down to Commentaries and Reflections on Paul Brunton and His Work below.

Book Details

Part 1, The Ego, is one of Paul Brunton's greatest and most unique gifts to the literature of realization—a truly earth-shaking piece of work for serious spiritual seekers. With no holds barred, it exposes, at an existential level, the most fundamental problems that obstruct achieving a life of unfailing self-integrity.

Part 2, From Birth to Rebirth, shows the role of death in the ongoing cycle of life, clarifies beliefs about reincarnation, and explores the creative relationships between fate, destiny, and free will.

Category Eight: THE EGO

INTRODUCTION

1. WHAT AM I?

Egoself and Overself

Body and consciousness

I-sense and memory

Ego as limitation

Ego as presence of higher

Two views of individuality

Perfection through surrender

Ego subordinated, not destroyed

Ego after illumination

Reincarnation

2. I-THOUGHT

I-sense and I-thought

Ego exists, as series of thoughts

Subject-object

3. PSYCHE

Ego as knot in psyche

The "subconscious"

Trickery, cunning of ego

Defense mechanisms

Self-idolatry

Egoism, egocentricity

4. DETACHING FROM THE EGO

Its importance

Why most people won't do it

As genuine spiritual path

Surrender is necessary

Its difficulty

Ego corrupts spiritual aspiration

Humility is needed

Longing for freedom from ego

Knowledge is needed

Tracing ego to its source

"Dissolution" of ego

Grace is needed

Who is seeking?

Results of dethroning ego

Category Nine: FROM BIRTH TO REBIRTH

INTRODUCTION

1. DEATH, DYING, AND IMMORTALITY

Continuity, transition, and transformation

The event of death

The aftermath of death

2. REBIRTH AND REINCARNATION

The influence of past tendencies

Reincarnation and Mentalism

Beliefs about reincarnation

Reincarnation and the Overself

3. LAWS AND PATTERNS OF EXPERIENCE

Defining karma, fate, and destiny

Karma's role in human development

Destiny turns the wheel

Astrology, fate, and free will

Karma, free will, and the Overself

4. FREE WILL, RESPONSIBILITY, AND THE WORLD-IDEA

The limitations of free will

The freedom we have to evolve

Human will in the World-Idea

“. . . a veritable treasure-trove of philosophic-spiritual wisdom.” —Elisabeth Kubler-Ross

“. . . sensible and compelling. His work can stand beside that of such East-West bridges as Merton, Huxley, Suzuki, Watts, and Radhakrishnan. It should appeal to anyone concerned personally and academically with issues of spirituality.” —Choice

“Vigorous, clear-minded and independent . . . a synthesis of Eastern mysticism and Western rationality. . . A rich volume.” —Library Journal

“. . . a great gift to us Westerners who are seeking the spiritual.” —Charles T. Tart

“A person of rare intelligence. . . thoroughly alive, and whole in the most significant, 'holy' sense of the word.” —Yoga Journal

For more reviews of the Notebooks series, click here

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category eight, The Ego

The Ego is a unique and unprecedented contribution to the literature of self-realization. It goes to the root of the most fundamental and immediate problem facing those who would live with unfailing self-integrity. It confronts this problem at an existential, rather than merely a psychological, level. As a result, the very reading of this material becomes a profitable spiritual exercise.

To make best use of the opportunity for lasting breakthrough which this section offers, the reader should recognize from the outset that this material abounds in information that the ego does not want its captive to hear. Further, every effort should be made to avoid premature judgements based on associations with other systems, especially psychological systems, where the word "ego" is used differently than here. Relentlessly probing and exploring, this section covers a broad range; its content is not readily reducible to a neat, tidy structure within which the ego-mind can feel comfortable. From high praise at one extreme to utter denigration at the other, it offers many viewpoints, explores many facets of the complex ego's origin, nature, and destiny. In its entirety, it leads masterfully beyond ordinary intellectualizing and into the intuitive realm of paradox where kernels of deep spiritual realization are lodged.

In structuring this material for publication, we found that any linear structure we came up with had serious limitations. The integrated wholeness of the insight behind this material demands being seen intuitively if it is to be seen clearly at all. The best approach we have seen is the one used by Anthony Damiani, a close and lifelong student of P.B. When first studying this section, he put individual paras on separate cards. He would read each one, then shuffle the "deck" randomly and read them all again. Reading in this way, he said, forced his mind to seek out and dwell in the insight behind the individual paras rather than in the associations his ego would construct between them.

What is true in general for reading The Notebooks, then, is especially true for reading the material in The Ego. The natural associative activity of the lower mind—its tendency to look for and make connections between independent thoughts—should be resisted, even suspended if possible, for the first few readings of the entire material. Individual paras should be meditated upon in and of themselves. The reader should compel his or her ego to let what is being said be heard.

Only after the entire range of viewpoints, the 360-degree perspective, has been assimilated will the radically transformative truths underlying surface contradictions gradually seep into the psyche and explain themselves. The reader's task for the present should be to savor each para, to take in each one as fully as possible. The inability to see readily how they can all fit together should not become a cause of anxious frustration. Careful study of the material will lead eventually to an integration, through Grace, of understanding at a deeper, now unconscious, level. In the meantime, we hope that the tentative structure we have provided for the purposes of publication in book form will at least not interfere with the working of the reader's intuition.

Editorial conventions are the same here as stated in introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that the para also appears in Perspectives, the introductory survey volume to this series.

EDITORS' INTRODUCTION for category nine, From Birth to Rebirth

From Birth to Rebirth focuses on two great problems of philosophy—our death and our destiny. These issues are especially relevant to our further understanding of the ego, as the ego is what recurrently is born and dies, and our conscious life in/as the ego is what the laws of recompense and free will affect.

Chapter one discusses the event of death, in our own lives and in the lives of others. It offers practical advice on helpful attitudes towards death and on how we can approach the experience of dying. It examines after-death states, our limited contact with those already dead, and our permanent connection to the immortal Overself now, and then.

In Chapter two, P.B. reflects on the cycle of life and death, through a consideration of teachings on reincarnation. Here he explores how one's own past reappears in present character, is active in the conditions of birth, and is a significant factor in all subsequent experiences. Many beliefs and superstitions surround this ancient doctrine and its significance in the journey toward wisdom. P.B. sorts through various historical modifications with his usual rational perspective to provide us with a clear, if somewhat complex, treatment of the subject.

Chapter three is a collection of P.B.'s remarks on karma, fate, destiny, and free will. Several paras in its first section indicate that P.B. considered these first three terms as interrelated but distinct forces or cosmic laws involved in the shaping of our lives and egos. The chapter's emphasis is on our experience of these laws: how to recognize their presence, and how our interaction with them may—or may not—change our circumstances. In this context, P.B. introduces a philosophic consideration of astrology, showing what it teaches us, how it can be used to help us understand our destiny, and how it can be misused. The chapter ends with a selection of paras examining free will from the perspective of destiny.

The final chapter deals with the question of free will: its limitations and opportunities, and our responsibility to use it wisely. We see here that death and rebirth, karma, fate, destiny, and limited free will are powers that shape the ego and bind its development to the larger evolution of the World-Idea. The section ends with paras in which P.B. reminds us of our heritage in the Overself, wherein lies freedom, refuge, guidance, and our true home.

Editorial conventions are the same here as stated in the introductions to Perspectives and The Quest. Likewise, (P) at the end of a para indicates that it also appears in Perspectives, the introductory survey volume to this series.

Excerpts from Notebooks category eight, The Ego

Prefatory:

The danger of most pseudo-spiritual paths is that they stimulate the ego, whereas the authentic path will suffocate it.

The best measuring-stick for progress is, in earlier stages, the degree of disappearance of the ego's rule and, in later ones, the degree of disappearance of the ego itself.

From chapter 1: WHAT AM I?

Egoself and Overself

1

That element in his consciousness which enables him to understand that he exists, which causes him to pronounce the words, "I Am," is the spiritual element, here called Overself. It is really his basic self for the three activities of thinking feeling and willing are derived from it, are ripples spreading out of it, are attributes and functions which belong to it. But as we ordinarily think feel and act, these activities do not express the Overself because they are under the control of a different entity, the personal ego.

2

The source of wisdom and power, of love and beauty, is within ourselves, but not within our egos. It is within our consciousness. Indeed, its presence provides us with a conscious contrast which enables us to speak of the ego as if it were something different and apart: it is the true Self whereas the ego is only an illusion of the mind.

3

Is it true that most men suffer from mistaken identity? That they are totally ignorant of the beautiful and virtuous, the aspirational and intuitive nature which is their higher self? The apathy which allows them to accept their lesser nature, their commonplace little self, must be found out for what it is.

4

Since the person a man is most interested in is himself, why not get to know himself as he really is, not merely as he appears to be?

5

Within every human entity there is a silent pull from within toward its centre, the real self. But alongside of this there is a stronger pull from without toward its instruments—the body's senses, the intellect, and the feelings—the false self. The entity is compelled to divide itself, its life and attention, between these two opposites, involuntarily through waking and sleeping, voluntarily through the ego surrendered to the Overself.

6

What is the ego but the Overself surrounded with barriers, conditioned by its instruments — the body, the feelings, and the intellect — and forgetful of its own nature?

7

The ego self is the creature born out of man's own doing and thinking, slowly changing and growing. The Overself is the image of God, perfect, finished, and changeless. What he has to do, if he is to fulfil himself, is to let the one shine through the other.(P)

8

Think! What does the "I" stand for? This single and simple letter is filled with unutterable mystery. For apart from the infinite void in which it is born and to which it must return, it has no meaning. The Eternal is its hidden core and content.

9

The ego is after all only an idea. It derives its seeming actuality from a higher source. If we make the inner effort to search for its origin we shall eventually find the Mind in which this idea originated. That mind is the Overself. This search is the Quest. The self-separation of the idea from the mind which makes its existence possible, is egoism.

10

What he takes to be his true identity is only a dream that separates him from it. He has become a curious creature which eagerly accepts the confining darkness of the ego's

life and turns its back on the blazing light of the soul's life.

11

Once this question — what am I? — is answered, there are no other questions. In the light of its dazzling answer, he knows how to handle all his problems.

12

The self which gives him a personal consciousness is not his truest self.

13

What does a man regard as himself? It is the conscious centre of all that he thinks and experiences, feels and does.

From chapter 2: I-THOUGHT

I-sense and I-thought

1

What we commonly think of as constituting the "I" is an idea which changes from year to year. This is the personal "I." But what we feel most intimately as being always present in all these different ideas of the "I," that is, the sense of being, of existence, never changes at all. It is this which is our true enduring "I."

2

If past and future are now only ideas, the present must be idea, too. So runs the mentalist explanation. But this can and should be carried still farther. If the experiencer of past and future is (because he is part of them) now an idea, then the experiencer of the present (and in the present) must be idea, too. As anything else than idea, he was (and is) only a supposition, which is the same as saying that the ego is only an apparent entity and has no more reality (or less) than any thought has.

3

Everything remembered is a thought in consciousness. This not only applies to objects, events, and places. It also applies to persons, including oneself, he who is remembered, the "I" that I was. This means that my own personality, what I call myself, was a thought in the past, however strong and however persistent. But the past was once the present. Therefore I am not less a thought now. The question arises what did I have then which I still have now, unchanged, exactly the same. It cannot be "I" as the person, for that is different in some way each time. It is, and can only be, "I" as Consciousness.

4

The "I"-consciousness is the essence of the "Me," the seeming self.

5

All that a man really owns is his "I." Everything else can be taken from him in a moment - by death or destiny, by his own foolishness or other people's malice. But no event and no person can rob him of his capacity to think the "I."

6

With the body, the thoughts, and the emotions, the ego seems to complete itself as an entity. But where do we get this feeling of "I" from? There is only one way to know the answer to this question: the way of meditation. This burrows beneath the three mentioned components and penetrates into the residue, which is found to be nothing in particular, only the sense of Be-ing. And this is the real source of the "I" notion, the self-feeling. Alas! the source does not ordinarily reveal itself, so we live in its projection, the ego, alone. We are content to be little, when we could be great.

7

That which claims to be the "I" turns out to be only a part of it, the lesser part, and not the real "I" at all. It is a complex of thoughts.

8

When the "I" is thought to be the body, appearance has replaced reality.

9

This feeling of I-ness may be associated with the body, emotions, and thoughts — whose totality is the personal ego — or shifted in deep meditation to the rootless root of being, which is the Overself; or, it may be associated with both, when one will be the reality and the other a shadow of reality.

10

The idea of a self first enters consciousness when a child identifies itself with bodily feelings, and later when it adds emotional feelings. The idea extends itself still later, with logical thoughts and, lastly, completes itself with the discovery of individuality.

11

Descartes' reference in his statement, "I think therefore I am," is simply to himself as a person, a self limited to body emotion and thought, that is, to ordinary experience and nothing higher or deeper than that, a being whose consciousness is unexamined and unexplored.

12

Ego means the consciousness of self.

Excerpts from Notebooks category 9, From Birth to Rebirth

From chapter 1: DEATH, DYING, AND IMMORTALITY

Continuity, transition, and transformation

1

Life-in-Itself is infinite and unchanging, but there is an end to the kind of experience undergone by the living entity in its finite human phase.

2

Just as sound goes back into silence but may emerge again at some later time, so this little self goes back into the greater being from which it too may emerge again at another time.

3

We worry ourselves through the days of an existence which is itself but a day. A profound sadness falls on the heart when it realizes the transient nature of all worldly things and all human being.

4

If decay and disintegration were not present at some stage, if our life spans were extended to say double their present length, then the old would outnumber all other sections of society. Stasis would overwhelm culture because the bodily slowdown would reflect itself mentally. The World-Mind had a better idea.

5

Human life steadily and unfailingly burns away like the candle in a man's hands.

6

Individuated life is forever doomed to die whereas the ALL which receives the dying can itself never die.

7

Even stars must die one day, more violently and dramatically than most human beings, for even they come under the law that whatever had a beginning must also have an ending.

8

We hear of other people dying and make suitable comment, but we do not feel that the time is coming when this fate will be ours too.

9

It is not so much because death deprives man of his possessions and relations that he dreads it, as the possibility that it deprives him of his consciousness - that is, his self, his ego.

10

Those who deplore, lament, or wail at the inevitability of death are viewing it in a very narrow, short-sighted way. The more mature ought to be thankful that we humans are not condemned to remain forever confined to a single body: this would indeed become a source of anxiety, if not of hopelessness.

11

Whether this bundle of personal desires and memories which is the ego, but which some of the pious call their soul, will be annihilated at death or perpetuated, is not an anxiety for the philosopher.

12

The more they enjoy the world the more they suffer when they leave it - unless they have learnt to put detachment behind the enjoyment.

13

No force can be destroyed; it can only be rechannelled. Life is a force; death is its rechannelling.

From chapter 4: FREE WILL, RESPONSIBILITY, AND THE WORLD-IDEA

The limitations of free will

1

The events of our future remain in a fluid state until a certain time. We have the free will to modify them during that period, although it is never an absolute freedom.

2

Inevitably and ultimately, will must prove stronger than fate because it is our own past will which created our present fate.

3

The awareness that they are weak and faulty makes some persons regard free will, not as the boon it is generally supposed to be, but as a danger. Saint Therese of Lisieux even asked God to take it away because it frightened her.

4

He who asserts that he is free to do what he wishes to do would more correctly state his situation by confessing that he is enslaved by his ego and goes up or down as its emotional see-saw moves.

5

It is not only the karma of a man which may oppose itself to his free choice and free will; there are also the possibilities of opposition by human institutions and organizations, natural calamities and catastrophes, genetic heredity and racial predisposition.

6

If a man's will were really free, he would have to think of using it before he actually did so, and then again to think of thinking of using it, and so on in an endless series. Since this situation never occurs, are we to believe that his will is never free? This is a question that no man can answer for it ought never to be put.

7

Even the man who believes that he possesses the attribute of free will finds himself forced to accept certain events just like others who do not believe they possess it.

8

Too many persons claim a freedom to choose and to will who in reality have only the very opposite — a captivity to their desires. These desires respond like a machine to the conditions which surround them and delude them into the belief that they are deliberately choosing from among those conditions. The moods and emotions of these persons are changed by every change of outer circumstance, provoked favourably or unfavourably by the nature of each change. Where is the freedom in this? Does it not rather show dependence?

9

Most human beings are so automatic and predictable in their habitual reactions that they are like machines. And where is the freedom of a machine? They are really helpless creatures, devoid of free will. Despite this, they do possess a latent freedom, even though they are not evolved enough to claim it.

10

A man imprisoned in the circle of his own ego still imagines he has free will!

In his own words:

“Writing, which is an exercise of the intellect to some, is an act of worship to me. I rise from my desk in the same mood as that in which I leave an hour of prayer in an old cathedral, or of meditation in a little wood . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 143

“P.B. as a private person does not count. There are hundreds of millions of such persons anyway. What is one man and his quest? P.B.’s personal experiences and views are not of any particular importance or special consequence. What happens to the individual man named P.B. is a matter of no account to anyone except himself. But what happens to the hundreds of thousands of spiritual seekers today who are following the same path that he pioneered is a serious matter and calls for prolonged consideration. Surely the hundreds of thousands of Western seekers who stand behind him and whom indeed, in one sense, he represents, do count. P.B. as a symbol of the scattered group of Western truth-seekers who, by following his writings so increasingly and so eagerly, virtually follow him also, does count. He personifies their aspirations, their repulsion from materialism and attraction toward mysticism, their interest in Oriental wisdom and their shepherdless state. As a symbol of this Western movement of thought, he is vastly greater than himself. In his mind and person the historic need for a new grasp of the contemporary spiritual problem found a plain-speaking voice . . .” —from Perspectives, volume 1 in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, p. 145

Learn more about Paul Brunton through articles at the Paul Brunton Philosophic Foundation web site

Electronic versions of this book are available from all major (Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble, Apple, Kobo, etc.) and most smaller ebook vendors. Please don't try to order ebooks directly from us, as we are not yet able to deliver anything to you in a preferred electronic format.

To see all our Paul Brunton titles, scroll down to The Complete Paul Brunton Opus below.

To see and/or order individual volumes in The Notebooks of Paul Brunton, hover your mouse over the specific cover in the Notebooks section of Complete Paul Brunton Opus below, then click on Details in the box that appears within it.

Click here to see or order the complete set of The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

Click here to see Standing in Your Own Way, Anthony Damiani's inspiring commentary on and development of the material in this volume.

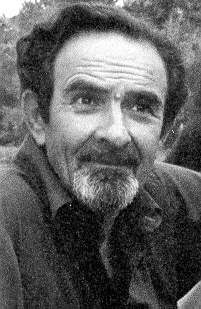

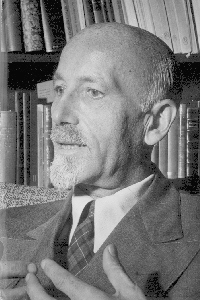

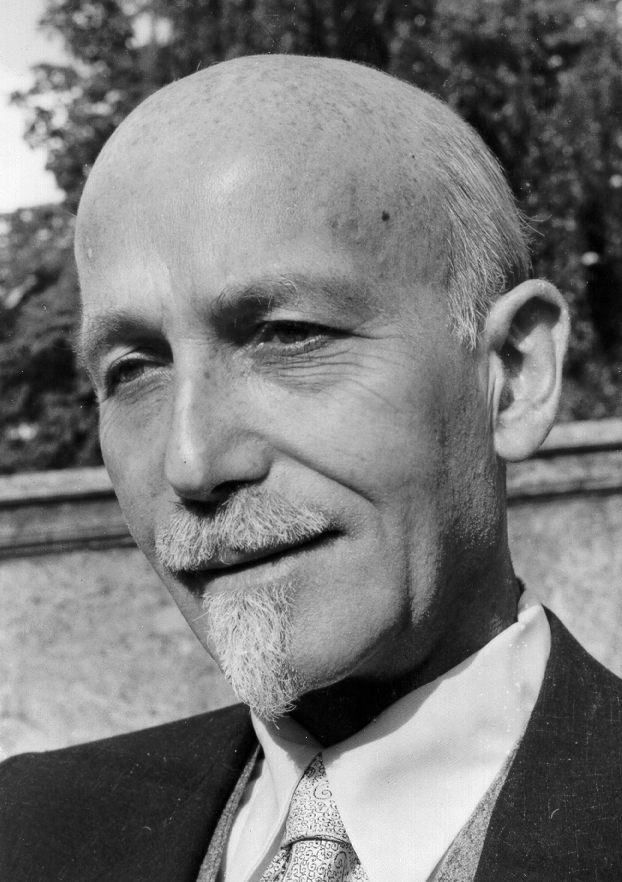

About Paul Brunton

Paul Brunton helps us hear the melody behind the medley of today's "spiritual marketplace." His late writings raise the bar for what we can expect of spiritual teachings and teachers, and what we can do for ourselves. Born in London in 1898, he soon became a leading pioneer of much of what we now take for granted. He traveled widely throughout the world (long before it was fashionable) to meet living masters of various traditions with whom he then lived and studied. His eleven early books from 1934–1952 shared much of what he learned, and helped set the stage for dramatic east-west exchanges of the late 20th century. Paul Brunton left more than 10,000 pages of enormously helpful new work in notebooks he reserved for posthumous publication, much of which is now available as The Notebooks of Paul Brunton. See "The Complete Paul Brunton Opus" in blue below to see his many works available on this site. You can also search on Paul Brunton in the search bar to browse the selections, or click on a link below for specific connections.

Click here for an article about Paul Brunton.

Click here for The Notebooks of Paul Brunton.

To access small theme-based books compiled from Paul Brunton's writings, scroll down to Derived from the Notebooks below.

To access Paul Brunton's early writings, published from 1934–1952, scroll down to Paul Brunton's Early Works below.

To access commentaries on Paul Brunton and his work by his leading student, Anthony Damiani, as well as other writings about Paul Brunton and/or his work, scroll down to Commentaries and Reflections on Paul Brunton and His Work below.

The Complete Paul Brunton Opus:

Paul Brunton's most mature work, in the order he specified for posthumous publication.

Smaller books on popular/timely themes, developed from the Notebooks and published posthumously.

Paul Brunton's works published during his lifetime from 1934-1952

Commentaries/Reflections by other authors on Paul Brunton or his works.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)